Share

Young adulthood is a unique time of life, filled with new experiences, new beginnings, and fraught with new obstacles and challenges. Young adulthood is a period that is developmentally associated with biological, psychological, social, and cognitive changes, along with increases in risk taking (Boles, Roberts, Brown, & Mayes, 2005). It is a time for adventure, when mortality is an abstract concept, inapplicable to the self and rarely, if ever, relevant to current circumstances and decisions. The influence of family and authority figures recedes as that of peers and social groups gains prominence. Social freedom becomes the new norm. With this, many of the protective factors defining adolescence weaken or disappear.

Rational thought may not be a reasonable expectation for young adults—there is a lot going on physically, in both the body and the brain, during young adulthood. Longitudinal neuroimaging studies demonstrate that adolescent brains continue to mature even when the subjects are well into their twenties (Johnson, Blum, & Geidd, 2009). While there is a tendency to feel “grown up” during young adulthood, neural connections between the amygdala (i.e., a limbic structure involved in emotional processing, especially of fear and vigilance) and the cortices that comprise the frontal lobe (i.e., where we make decisions and exercise logic) are still developing. These connections are becoming denser and this density is a measure of the growth of connections within the brain. These connections form networks and are the pathways that will be used in making decisions, both conscious and unconscious, throughout the life span.

These connections integrate emotional and cognitive processes and result in what is often considered to be “emotional maturity” (i.e., the ability to regulate and to interpret emotions). Evidence suggests that this integration process continues to develop well into adulthood. Interrupting or disturbing the growth and development of these pathways can have lasting effects.

Young Adults and SUDs

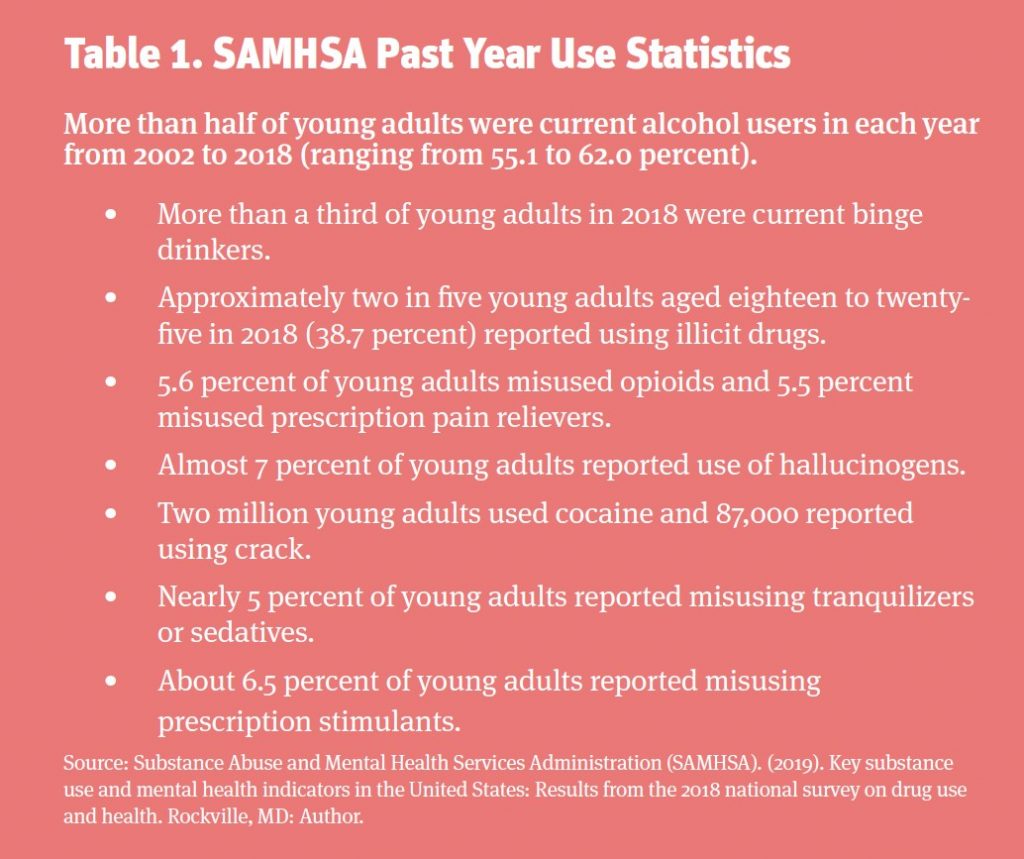

Young adults are often vulnerable to substance misuse and the development of use disorders. Substance use disorders (SUDs) are highly prevalent among young adults (Hingson, Heeren, & Winter, 2006), the median age of onset for SUDs is twenty years of age (Kessler et al., 2005), and SUDs have experienced the most rapid increase in prevalence in the adolescent and young adult years (Kessler et al., 2007). Furthermore, starting to drink at an early age is associated with alcohol dependence and related problems during adulthood (Hingson et al., 2006). About 67 percent of individuals with a lifetime history of alcohol dependence met criteria prior to age twenty-five (Hingson et al., 2006).

In a study of a large national data set, frequent heavy drinkers are more likely to engage in risky behaviors such as riding with drinking drivers; driving after drinking; suicide attempts; having unplanned and unprotected sex; using tobacco, marijuana, and other illicit drugs; drinking and smoking marijuana at school; and earning mostly low grades—D’s and F’s—in school (Hingson et al., 2006).

Young Adults and Mental Health Disorders

Seventy-five percent of mental health disorders are diagnosed by age twenty-four, and young adults have three times the suicide rate of their adolescent (i.e., twelve- to seventeen-year-old) counterparts (Park, Mulye, Adams, Brindis, & Irwin Jr., 2006). According to data for 2018, approximately 8.9 million young adults (26.3 percent) had a mental illness in the past year and 7.7 percent had a serious mental illness, reflecting continued growth in the number of young adults with mental illnesses since 2008 (SAMHSA, 2019). Similarly, in 2018, nearly one in seven young adults experienced a major depressive episode in the past year, while almost 9 percent of this population had a major depressive episode in the past year with severe impairment in 2018 (SAMHSA, 2019). Both these percentages represent consistent growth since 2005.

There are many factors that can contribute to substance misuse and the development of substance use and mental health disorders in young adults. Living outside the direct influence of a parent—for example, living outside the family home—has been associated with higher likelihood of marijuana and alcohol use (Gfroerer, Greenblatt, & Wright, 1997). Young adults are less likely to recognize or subscribe to the possibility of negative consequences related to drug use behaviors. Social networks and peer groups have strong influences on young adults. While these networks can have positive influences, some research suggests that it is more common for young adults to be negatively influenced by peer groups (Astudillo, Connor, Roiblatt, Ibanga, & Gmel, 2013).

The Role of Trauma

Of all the possible risk factors contributing to the development of substance abuse and mental health disorders, perhaps the most significant is a history of trauma. The term “trauma” refers to an emotional response to a disturbing event. Some common sources of trauma include natural disasters, accidents, and acts of violence, but one of the most interesting features of trauma is that it is personal in nature. It is not the actual experience that defines if individuals have trauma, but their emotional response to the experience. Trauma threatens individuals’ sense of safety beyond the traumatic experience and is often diagnosed by cataloging symptoms both psychological and physical. Like trauma itself, the symptoms can vary widely by individual.

Trauma can be the result of a single event or of ongoing and persistent high levels of stress. There is evidence that it can be transmitted genetically as well. Trauma leaves a genetic mark that multiple generations after the event can continue to be affected by. People can also experience trauma by observing an event, even if not actively involved. Similarly, perpetrators of violent acts may themselves also experience trauma as a result of the acts.

Research has demonstrated that psychological trauma can be seen as an injury to the brain, with physiological changes similar to those seen in physical trauma. Investigations using cohorts of military personnel report that, from a neural perspective, the same regions of the brain appear to be impacted by both traumatic biomechanical injury and psychological trauma (McAllister & Stein, 2010). Trauma can alter brain functioning in a number of ways, and of particular importance are the effects of trauma on the areas that control thought processes (the prefrontal cortex), emotional regulation (the anterior cingulate cortex), and fear responses (the amygdala). These areas of the brain are undergoing critical developmental changes during young adulthood, which highlights the importance of recognizing trauma during that phase of development.

It is well established that trauma plays a significant role in the development of SUDs. Some estimates claim that traumatic experiences increase the likelihood of abusing alcohol and/or injecting drugs up to four-fold (Kerr et al., 2009). A great deal of research has been reported on the role of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs; Felitti et al., 1998) and the development of substance abuse and mental health disorders. High rates of abuse of various substances have been found to be associated with childhood trauma (McAllister & Stein, 2010). Similarly, research has been conducted to review the roles of other types of trauma on substance use. As many as 33 percent of people who survive trauma related to an accident, illness, or disaster report problem alcohol use (ISTSS, n.d.). Research has also shown high rates of substance abuse in survivors of sexual abuse, sexual assault, and violence (Miranda Jr., Meyerson, Long, Marx, & Simpson, 2002).

The development of SUDs can begin with the use of alcohol and drugs as a coping mechanism for the symptoms of trauma. The symptoms of trauma can be very disruptive to daily life and disturbing to the people experiencing them. Among the symptoms are intrusive thoughts, mood swings, sleep disorders, anxiety, difficulty concentrating, and hypervigilance. Nowlin and Brown (2019) found that trauma effects several areas of functioning independent of a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Assessing for trauma is an important part of determining patient needs. Accrediting bodies like The Joint Commission require trauma assessment, but this does not extend to private practices and other settings. Mental health providers may offer questions at intake, but these should be extended to include questions about familial issues, sleep issues, head injuries, accidents, sports injuries, disasters, and other potential sources of trauma.

Research on college students shows that college campuses are one of the most frequent locations in which sexual violence occurs. Approximately 11 percent of all college students experience rape or sexual assault during their time engaged in undergraduate- or graduate-level education (Cantor et al., 2015). Although studies show that there are more female college students who report accounts of unwanted sexual contact (about 23 percent), there is gender similarity in terms of the context of unwanted sexual experiences (Banyard et al., 2007). This percentage is even more increased for the transgender, genderqueer, and nonconforming (TGQN) population of college students (Cantor et al., 2015).

The effects of trauma on young adults’ developing brains can be devastating. Young adults are less likely than their older counterparts to have developed adequate and healthy coping mechanisms. As trauma effects the areas of the brain undergoing some of the most significant transformations during the young adult years, trauma during young adulthood—combined with the other social, environmental, and developmental factors described previously, including the higher risk of substance use initiation, mental health disorder vulnerability, and risk-taking behaviors—is of particular concern. Adding the misuse and abuse of substances only exacerbates an already difficult situation and risks further damage to the developmental processes critical to this time period.

Intervening with Young Adults

Young adults are risk averse. That is the nature of being a young adult: the ability to both withstand consequences and to deny the inevitability of future results. As previously described, there are developmental processes in progress allowing the recognition of cause and effect, but these are not fully developed in young adults. Further, young adults, for physiological reasons, often act from the emotional side of their brains as opposed to the executive.

One of the biggest myths about seeking help is that help may not be effective until individuals have hit “rock bottom.” In the case of young adults, this can be deadly advice. Often family and friends need support in getting their young adult loved ones to enter treatment. Interventions, of which there are several models, are one of the ways for professionals to offer this support. For trained mental health care professionals, intervention training can be an important tool in their toolkit.

Intervening is about stopping the addiction process and its related effects. An intervention aims to prevent further consequences such as arrest, jail, family dysfunction, relationship issues, financial consequences, and possibly death. In truth, there is no “rock bottom”; a bottom is reached when individuals stop progressing on that particular path or stop “digging.” The experience of rock bottom is very personal, and intervening to prevent further consequences requires both rapport with patients as well as the ability to hold strong boundaries.

Most intervention styles work to create a nonjudgmental environment, and many seek to avoid dramatic confrontation. Several models actively include the family, which can also be expanded to include nonbiological relationships that are significant, important, and that have a positive influence on young adult patients. Creating a supportive, nonshaming environment is critical to the family communication dynamic and the effectiveness of the intervention. Observing family interactions, supporting families in creating and holding boundaries, and having clear, agreed-upon objectives at the outset are key features to effectively intervening in young adult substance abuse.

Young adults are less likely to be self-motivated to enter treatment for substance abuse problems (Goodman, Peterson-Badali, & Henderson, 2011) and more likely to enter treatment as a result of external factors (Morse & MacMaster, 2014). Thus, entry into treatment is often set in motion by an event or crisis that can sometimes trigger feelings associated with past trauma, exacerbating young adults’ addictive behaviors. The event or crisis can also be the source of trauma that pushes social behavior over the edge.

Interventions are often preceded by an event or crisis. It is imperative that interventionists know about recent trauma and craft their intervention plans acknowledging its impact. Significant damage can be done if the intervention focuses on blaming and shaming any participants, particularly young adult patients, as leverage for treatment entry. Shame is more often a reason to avoid seeking help than an impetus to get treatment. Research suggests that positive therapeutic interactions with SUD patients can impact their ability to rebuild familial and other relationships (Wheeler, Morse, & MacMaster, 2020).

The crisis intervention is a specific type of intervention that requires minimal training for mental health professionals and can be very effective, especially in situations where a recent crisis or traumatic event triggers the need for intervention. The process uses principles of neurolinguistic programming, motivational interviewing (MI), and de-escalation techniques that can be particularly effective in supporting treatment entry decisions in young adults. In most cases, crisis interventions can be accomplished successfully in a matter of hours.

Neurolinguistic programming can be seen as acknowledging the nonverbal part of the conversation as well as the unconscious thought patterns that often source behavior and mood. Acknowledging these aspects of the communication process and using certain techniques to guide the interactions can support the effectiveness of communication and achieving the goals of behavior change and treatment entry. MI principles are used to strengthen motivation and build a plan for change. By supporting young adult patients in making decisions (as opposed to deciding for them), the techniques of MI can begin to shift the motivation to internal and support engagement in the treatment process. De-escalation is helpful in most interventions as well, particularly in those working with young adults. Young adults are still operating from the emotional center of their decision-making capacity, and family dynamics can run hot.

Research suggests that the likely use of treatment services is determined by many predisposing characteristics such as demographics, attitudes toward treatment or illness, family alignment and support, and needs-related characteristics such as severity of addiction (Wu, Pilowsky, Schlenger, & Hasin, 2007). When advising on treatment, interventionists should consider the unique characteristics of their young adult patients in relation to the recommended treatment facilities. With the combination of a tactful intervention style and thoughtful matching of patient to facility, not only is treatment more likely to be part of young adults’ paths to recovery, but also there is a greater likelihood for treatment engagement from the outset, increasing the probability of positive long-term outcomes. Individuals entering treatment have a significantly lower rate of relapse, increased self-efficacy, and greater likelihood of seeing their substance use as a problem (Moos & Moos, 2006), all factors that support these young adults in developing new coping strategies and life paths.

The Family Role

Success in treatment is also affected by the role of the family. The family’s role in activating and participating in interventions for young adults cannot be understated. Supportive, nonshaming conversations are significantly more effective at engaging young adults. Often, family pressures and issues are associated with substance use behaviors. A cross-sectional research study comparing cohorts of opioid-abusing patients found that reported family issues are a significantly increased problem for those entering treatment over time (Wheeler, Morse, & Bride, 2019).

Not only do the users experience the repercussions of addiction, but their entire families are affected by the members suffering from an addiction (Stanton et al., 1978). As young adults move farther into substance abuse, the risk of isolation steadily increases, which continually heightens strain in the familial relationship. Family support and involvement in this process is a crucial matter for many patients, and significantly so for the young adult population.

Summary and Conclusion

Entering treatment exposes young adults to new opportunities and tools for recovery. A variety of therapy styles can be offered in treatment centers, contingent on where patients choose to attend, that help develop necessary recovery skills. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a scientifically proven, goal-oriented, psychotherapy technique used to develop skills in changing patterns of thoughts. MI is another widely used technique that is a client-centered counseling style for eliciting behavior change. Peer approval plays a significant role in young adult life, and the therapeutic community offered through residential treatment or sober housing can provide important support and social learning for this population. These treatments—along with those addressing family issues, medication management, and community building—are aimed at treating the whole person (NIDA, 2020). Patients in treatment are more likely to utilize Twelve Step and other peer-led recovery programs that increase the probability of increased sobriety (Moos & Timko, 2008).

Interventions are an important pathway for young adults to enter treatment. For therapists, understanding the role of crisis interventions and learning the skillset to perform them can create pathways for young adult patients to receive important treatment. Incorporating knowledge of patients’ past and possibly current traumas into the intervention plan can support the effectiveness of interventions, treatment engagement, and ultimately positive outcomes.

References

- Astudillo, M., Connor, J., Roiblatt, R. E., Ibanga, A. K. J., & Gmel, G. (2013). Influence from friends to drink more or drink less: A cross-national comparison. Addictive Behaviors, 38(11), 2675–82.

- Banyard, V. L., Ward, S., Cohn, E. S., Plante, E. G., Moorhead, C., & Walsh, W. (2007). Unwanted sexual contact on campus: A comparison of women’s and men’s experiences. Violence and Victims, 22(1), 52–70.

- Boles, R. E., Roberts, M. C., Brown, K. J., & Mayes, S. (2005). Children’s risk-taking behaviors: The role of child-based perceptions of vulnerability and temperament. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 30(7), 562–70.

- Cantor, D., Fisher, B., Chibnall, S., Townsend, R., Lee, H., Bruce, C., & Thomas, G. (2015). Report on the AAU campus climate survey on sexual assault and sexual misconduct. Retrieved from https://www.aau.edu/sites/default/files/AAU-Files/Key-Issues/Campus-Safety/AAU-Campus-Climate-Survey-FINAL-10-20-17.pdf

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., . . . Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 14(4), 245–58.

- Gfroerer, J. C., Greenblatt, J. C., & Wright, D. A. (1997). Substance use in the US college-age population: differences according to educational status and living arrangement. American Journal of Public Health, 87(1), 62–5.

- Goodman, I., Peterson-Badali, M., & Henderson, J. (2011). Understanding motivation for substance use treatment: The role of social pressure during the transition to adulthood. Addictive Behaviors, 36, 660–8.

- Hingson, R. W., Heeren, T., & Winter, M. R. (2006). Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: Age at onset, duration, and severity. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 160(7), 739–46.

- International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS). (n.d.). Traumatic stress and substance abuse problems. Retrieved from https://www.istss.org/ISTSS_Main/media/Documents/ISTSS_TraumaStressandSubstanceAbuseProb_English_FNL.pdf

- Johnson, S. B., Blum, R. W., & Giedd, J. N. (2009). Adolescent maturity and the brain: The promise and pitfalls of neuroscience research in adolescent health policy. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 45(3), 216–21.

- Kerr, T., Stoltz, J. -A., Marshall, B. D. L., Lai, C., Strathdee, S. A., & Wood, E. (2009). Childhood trauma and injection drug use among high-risk youth. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 45(3), 300–2.

- Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 593–602.

- Kessler, R. C., Amminger, G. P., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Lee, S., & Ustün, T. B. (2007). Age of onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 20(4), 359–64.

- McAllister, T. W., & Stein, M. B. (2010). Effects of psychological and biomechanical trauma on brain and behavior. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1208(1), 46–57.

- Miranda Jr., R., Meyerson, L. A., Long, P. J., Marx, B. P., & Simpson, S. M. (2002). Sexual assault and alcohol use: Exploring the self-medication hypothesis. Violence and Victims, 17(2), 205–17.

- Moos, R. H., & Moos, B. S. (2006). Rates and predictors of relapse after natural and treated remission from alcohol use disorders. Addiction, 101(2), 212–22.

- Moos, R. H., & Timko, C. (2008). Outcome research on twelve step and other self-help programs. In M. Galanter, & H. D. Kleber (Eds.), Textbook of substance abuse treatment (4th ed.) (pp. 511–21). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

- Morse, S. A., & MacMaster, S. (2014). Characteristics and outcomes of college-age adults enrolled in private residential treatment: Implications for practice. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 14(1), 6–26.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). (2020). Drugs, brains, and behavior: The science of addiction. Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugs-brains-behavior-science-addiction/preface

- Nowlin, R. B., & Brown, S. K. (2019). Recognizing and treating trauma in an inpatient psychiatric setting. Psychiatric Times. Retrieved from https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/recognizing-and-treating-trauma-inpatient-psychiatric-setting

- Park, M. J., Mulye, T. P., Adams, S. H., Brindis, C. D., & Irwin Jr., C. E. (2006). The health status of young adults in the United States. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 39(3), 305–17.

- Stanton, M. D., Todd, T. C., Heard, D. B., Kirschner, S., Kleiman, J. I., Mowatt, D. T., Van Deusen, J. M. (1978). Heroin addiction as a family phenomenon: A new conceptual model. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 5(2), 125–50.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2019). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 national survey on drug use and health. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018.pdf

- Wheeler, J., Morse, S. A., & Bride, B. (2019). Opioid usage trends in treatment – Trends from the field. International Journal of Healthcare, 5(1), 29–32.

- Wheeler, J., Morse, S. A., & MacMaster, S. (2020). Patient experiences of compassion in treatment lead to better outcomes [Internal report, Foundations Recovery Network]. Unpublished.

- Wu, L. -T., Pilowsky, D. J., Schlenger, W. E., & Hasin, D. (2007). Alcohol use disorders and the use of treatment services among college-age young adults. Psychiatric Services, 58(2), 192–200.

Karyn Hurley, BHS, CHAP, NCIT

Karyn Hurley, BHS, CHAP, NCIT, has worked in the addiction field for thirty-five years, beginning as a recovery nutritional therapist and eventually becoming a published author and program director. Her passion is to provide knowledge and education to assist others on their recovery journey.

Scott Jones, BSW, NLP, CHAP, NCIT

Scott Jones, BSW, NLP, CHAP, NCIT, began his career in advertising and marketing with successful television and radio shows in the Philadelphia-Atlantic City media market. He then applied those skills as a social worker for the state of New Jersey. Jones later transitioned into working directly with recovering addicts in the areas of residential recovery, addiction brain chemistry, and program management.

Siobhan A. Morse, MHSA, CRC, CAI, MAC

Siobhan A. Morse, MHSA, CRC, CAI, MAC, is divisional director of clinical services, responsible for research and special projects, at Universal Health Services’ (UHS) Behavioral Health Division. Morse works closely with over 250 UHS facilities to champion optimization and standardization of clinical protocols, evidence-based outcomes methodology, and publication of clinical research. Her current focus targets helping serve OUD patients across the entire UHS system. Morse also serves as a voluntary adjunct professor with Baylor University College of Family Medicine.

Jeri Ann Wheeler, MSW

Jeri Ann Wheeler, MSW, is a research associate and counselor at Foundations Recovery Network, the Addiction Services Division of UHS. She holds a master’s degree in clinical rehabilitation counseling and is certified as a national counselor (NCC). Along with her clinical counseling work in the addiction field, she has conducted research and analysis at the Georgia Institute of Technology and at Georgia State University. Research fields include autism spectrum disorder, marriage counseling dynamics, and childhood development.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.