Share

About 25 to 50 percent of justice-involved youth (JIY) have a substance use disorder (SUD; Teplin, Abram, McClelland, Dulcan, & Mericle, 2002; Wasserman, McReynolds, Ko, Katz, & Carpenter, 2005; McClelland, Elkington, Teplin, & Abram, 2004), compared with 4 percent of general population youth (Merikangas et al., 2010). Left untreated, substance use among JIY is associated with numerous negative outcomes, including longer-term SUD issues into adulthood (Winters & Lee, 2008; Englund, Egeland, Oliva, & Collins, 2008; Stone, Becker, Huber, & Catalano, 2012; Swift, Coffey, Carlin, Degenhardt, & Patton, 2008), further justice involvement (Hoeve, McReynolds, Wasserman, & McMillan, 2013; Loeber, Farrington, & Waschbusch, 1999; Loeber, Stouthamer-Loeber, Van Kammen, & Farrington, 1991; Henggeler, Clingempeel, Bronidon, & Pickrel, 2002), violence (Copeland, Miller-Johnson, Keeler, Angold, & Costello, 2007; Loeber et al., 2005), and early death (Kann et al., 2018).

Although substance use treatment in adolescence has been shown to reduce the likelihood of these negative outcomes among JIY (Cuellar, Markowitz, & Libby, 2004; Hoeve, McReynolds, & Wasserman, 2014), about 50 to 80 percent of JIY with SUDs are still not in treatment (Belenko & Dembo, 2003; Kataoka, Zhang, & Wells, 2002; Novins, Duclos, Martin, Jewett, & Manson, 1999; Johnson et al., 2004). There are several intervention points at which JIY with SUDs can be identified and linked with treatment, including while youth are under the care of the probation system. However, at each point of the pathway into treatment—identification, referral, initiation, and retention in treatment—there are missed opportunities to address substance use issues among JIY (Belenko et al., 2017).

Probation as a Critical Point of SUD Intervention

In most jurisdictions, complaints regarding delinquent conduct are referred to and reviewed by probation or court authorities (Wasserman et al., 2009; Burke et al., 2019). These referrals may result in no action, formal processing that could result in either formal supervision or juvenile detention, or in the majority of cases, adjustment and informal supervision (Burke et al., 2019) where youth are able to remain in their communities under the care of the probation system. This period of supervision can serve as a critical intervention point at which probation can screen for and identify youth with SUDs, link youth with local community treatment services, and support the treatment process for JIY. Effective interventions can help successfully rehabilitate youth, help them maintain within their communities, and divert JIY with SUDs away from further, more serious justice system involvement (Fisher et al., 2018). Thus, probation officers are tasked with both the more traditional role of protecting community safety as well as facilitating the rehabilitation of and reducing the risk of recidivism among the JIY on their caseload.

Cross-Systems Collaboration: Probation, Family, and Treatment

The probation system cannot successfully link JIY to substance use treatment on its own. Successful linkage requires buy-in, engagement, and collaboration among the probation system, treatment system, and family system. This collaboration is particularly challenging to achieve, since each of these three systems operates with its own priorities and goals, often competing and conflicting with one another.

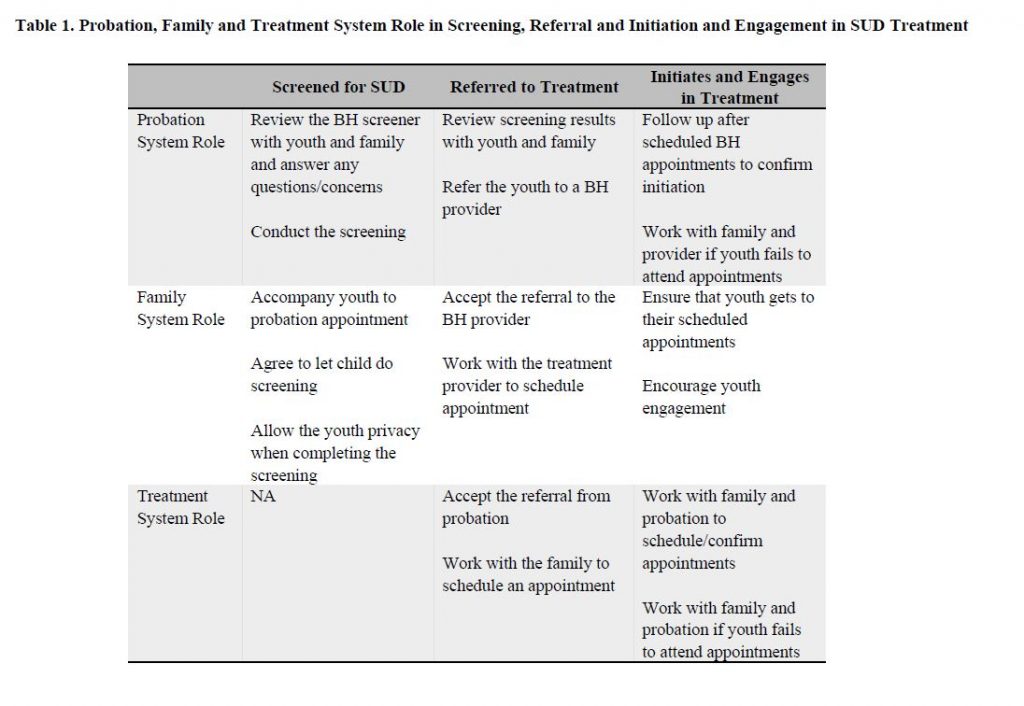

Probation, Family, and Treatment System Roles in the Pathway into SUD Treatment

Table 1 provides a simple overview of each system’s role along the process of screening, referral, treatment initiation, and engagement. As depicted in Table 1, probation screens youth and then refers them to community-based providers who can provide further assessment and SUD treatment, relying on their families to participate in this process by allowing the screening, accepting the referral, working with the treatment provider to schedule appointments, and making sure that youth attend their appointments. The probation and treatment system must collaborate to confirm that youth are attending their appointments and work together to intervene when they are not. Thus, each system plays a critical role, both independently and in partnership with one another, in facilitating and monitoring the uptake of SUD treatment services among JIY.

When these three systems fail to collaborate effectively across the stages of screening, referral and initiation, youth do not receive the treatment they need (Wasserman et al., 2009). Even when youth are screened and identified with behavioral health needs (e.g., substance use need, mental health need, or both), probation linkage activities are not always enacted nor do efforts to address identified behavioral needs always make it into youths’ case plans (Wasserman et al., 2008). According to a review of case records for juvenile intakes in four county juvenile probation offices in New York State, probation officers only referred approximately 30 percent of youth with identified behavioral health needs to treatment providers. For the other 70 percent, contacting treatment providers prior and securing appointments was left to youth or their families to do on their own. Thus, a valuable opportunity for probation to facilitate and oversee the integration of youth and their families into the treatment system was lost. Furthermore, of the youth who were referred to treatment, probation confirmed service initiation for fewer than half (Wasserman et al., 2008). These findings allude to cross-systems communication and collaboration breakdowns across the referral and initiation process.

Most work examining these issues to date have studied facilitators and barriers to SUD treatment among JIY by examining youth/caregivers, the justice system, or the treatment system independently, despite how interdependent these systems are within the context of SUD identification and treatment linkage. Thus, researchers from Columbia University examined the experiences of probation staff (n=11), substance use providers (n=27), and youth on probation and their caregivers (n=10 pairs) via in-depth interviews or focus groups, integrating responses in order to provide a fuller picture and more completely understand specific facilitators and barriers to the use of substance use services in youth on probation (Elkington, Lee, Brooks, Watkins, & Wasserman, 2020).

Cross-System Barriers to Treatment Initiation and Engagement

Overall, the interviews across all responders revealed that family engagement with both the probation and treatment systems across the referral and initiation process is essential to youth initiation and engagement in treatment, and was reportedly lacking according to probation, treatment providers, and families themselves. Similarly, the engagement of probation and treatment systems with each other also emerged as critical to this process. A summary of some key findings are provided next, including direct quotes from study participants.

Barriers to Family Engagement

Distrust in the System

Probation officers and substance use providers both identified family distrust in the system as a main reason why families fail to initiate and remain in treatment. Substance use providers noted an important distinguishing factor: unlike non-justice-involved families, the decision to seek treatment is made from an external system (e.g., probation) and not from within family units. Moreover, families might question probation’s motivation for issuing these referrals. Caregivers reported fears about the system wanting to separate families, which may reduce willingness to accept referrals or ensure that youth initiate treatment. One thirty-two-year-old mother stated,

The system doesn’t really care about anybody and there’s a bunch of people that work there that probably don’t . . . ‘Okay, this is going on, we’re going to go over there and just split everybody up.’ So why should we talk to them? Why would I let my teen go?

Substance use providers noted that since many families of youth on probation have also been involved with other services (e.g., child welfare), substance use treatment might just represent another service for families to engage with—one that may not be perceived to operate fairly or transparently. For youth who do initiate treatment, families are less engaged than non-justice-involved families who brought youth there out of their own concern. Youth also reported that being referred to substance use treatment after it had become such a problem in their lives was unhelpful and potentially could lead to increased use.

Denial or Minimization of Substance Use Problems

Probation officers and substance use providers have noted that parents tend to downplay or minimize youth substance use issues, leading to consistent disagreements between families, probation officers, and/or substance use providers about the necessity of treatment. According to probation and treatment providers, this minimization is also significantly driven by the caregivers’ and/or families’ own substance use as well as concerns about having their behavior exposed and how it might affect family dynamics. A substance use provider explained,

I think a lot of the kids are afraid that what’s going to happen—what we’re going to hear here—is going to impact the family dynamics, because in a lot of these cases the parents are actively using and the kid is like sitting in that courtroom as the problem. And that’s serving a really specific function; the kid’s use is serving a function in that family system. So to disturb that is disturbing the whole . . . like the whole house of cards is going to come down.

Caregivers admitted to experiencing shame about having failed to identify and/or address their child’s substance use issues on their own. Additionally, they have reported experiencing stigma from probation officers and substance use treatment providers who might blame them for their child’s use and their failure to provide a stable home environment. A fifty-eight-year-old mother noted,

Everybody tries to focus on the parents, you know, and I’m sure in some cases do. I know they try to find where the problem could have started, or what could have caused it. I understand that, but it gets so repetitious, like, “No, I don’t beat my children. No, there’s no sexual abuse. No, I don’t drink. No, I don’t smoke.” It just . . . it gets kind of upsetting sometimes.

This shame and perceived blame might further prompt distrust in the system and make families less likely to want to cooperate with probation officers and substance use providers.

Relational Barriers

Probation officers and substance use providers indicated that relational difficulties between parents and youth—the parents feeling overwhelmed and no longer willing to fulfill the parental role—made it difficult for these systems to facilitate youth recovery. Caregivers play a critical role in ensuring that youth make it to treatment. Without caregivers’ investment in the process, youth are unlikely to show up and engage.

Overburdening within the Family System

Probation officers and substance use providers both discussed that the family system must manage youth treatment in the face of multiple competing demands (e.g., low social support, financial strains), which might result in treatment being placed towards the bottom of a hierarchy of competing needs and requiring treatment providers to be flexible about the treatment course. Probation officers, substance use providers, and families cited that many caregivers work multiple jobs and have limited time and financial resources to take youth to appointments. Beyond that, lack of insurance and appointment copays were also cited as additional barriers by all three systems. A female probation officer, age fifty-four, mentioned the following:

The one thing would be maybe their expectation that the youth attends program three times a week, and me knowing that, you know, this kid is dependent on a mom who works overnight, and who is half asleep, and they don’t have the money in their grip.

Even when youth do attend treatment, providers noted that chaotic family systems or environments made it difficult for youth to remain in treatment or achieve long-term behavior change.

Barriers to Interagency Collaboration among Probation and Treatment Systems

Treatment Agency Policies and Procedures

Probation staff cited treatment agency policies—specifically that probation officers cannot schedule appointments on behalf of families—as a significant barrier to their ability to successfully refer youth to treatment, since they then had to rely on families to contact treatment staff on their own. As mentioned previously, caregivers and/or youth are often hesitant or resistant to attending treatment, and families are often overtaxed and stressed to begin with. Thus, this policy delays or completely prevents the first critical step to attendance (i.e., making the appointment) from occurring, putting strain on the probation and family systems independently and on their already-complicated relationships, with probation officers having to follow up with and encourage reluctant families to schedule appointments.

Additionally, probation and treatment staff mentioned that poorly defined or developed referral and linkage procedures make it difficult to efficiently and quickly schedule youth appointments, with probation staff citing that the treatment system often offered appointment times that conflicted with school hours or were otherwise unsuitable for youth and their families. Thus, even if families do reach out to treatment to make an appointment, the process might still result in no appointment or a significantly delayed appointment depending on provider availability.

Interagency Collaboration and Communication: Punishment vs. Rehabilitation

Although both probation and treatment agencies reported that effective communication and collaboration was critical to achieving successful treatment linkage, they cited two major barriers to achieving it:

- Role confusion with respect to who was responsible for holding youth and families accountable for treatment attendance

- Differing philosophies about what meaningful treatment ought to look like (e.g., abstinence versus harm-reduction approaches)

Role confusion over how to enforce treatment attendance allows youth to “slip through the cracks” between the probation and treatment systems. Probation officers were wary to punish youth for missing appointments for fear of getting them into further trouble and entrenching them further within the justice system, especially since SUD treatment is seen as supplemental rather than a primary part of their probation supervision. This frustrates their treatment partners, who believe that probation ought to more strictly enforce attendance. For example, one probation officer noted,

So to me, for continuing to smoke marijuana while he’s going to program once a week, I’m not going to make a recommendation to pull a kid—a teenage kid—out of his home, send him to a detention center (with kids who stab, rape, hurt people), because he’s in treatment . . . So that’s a treatment issue. That’s not a detention issue. If he hasn’t gotten arrested or he hasn’t hurt anyone, there’s no way I’m bringing him to court.

Somewhat contradictorily, probation officers often held more rigid beliefs about what meaningful treatment was (i.e., abstinence) compared with harm-reduction approaches employed by substance use treatment staff, resulting in discord among the two systems. Substance use providers disagreed with fear-based tactics used by probation officers to enforce abstinence and disclosed being hesitant to reveal when JIY were struggling with treatment because of this. These differing philosophies among the two systems made it difficult for them to work together to support the youth on their caseloads.

Suggestions for Practice

While probation officers can help link youth with treatment, families play a key role in ensuring their youth move between two systems. Families can serve as bridges connecting youth to probation and treatment. However, findings indicate a number of family-level perceptions that effect the relationships between family systems, probation, and treatment, which can challenge successful engagement. Enhancing family engagement at the point of referral to substance use treatment is essential. Among JIY who are referred to SUD treatment from probation, treatment agencies must maintain awareness of the circumstance that the referral is coming from an outside (and in some cases distrusted) source, so efforts to build families’ trust and support at the early stages are essential to ensure that treatment appointments are scheduled and attended.

It is also critical that probation and treatment both recognize and understand one another’s roles and determine how to collaborate. Developing clear expectations about what each agency—that is, probation and SUD treatment providers—will do in terms of scheduling, sharing information about the treatment/supervision process, and enforcing appointment attendance might help ensure that youth and families are able to successfully work with and transition between the two systems throughout the course of treatment.

Taken together, findings suggest that interventions promoting collaboration between justice and treatment systems as well as engaging families may be successful in achieving treatment linkage that starts in the probation agency and successfully moves youth into substance use treatment within their communities. Use of linkage specialists to accomplish coordination and engagement across all three systems, with a strong focus on working intensively with families outside the context of the justice system, may prove successful component of such interventions.

References

- Belenko, S., & Dembo, R. (2003). Treating adolescent substance abuse problems in the juvenile drug court. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 26(1), 87–110.

- Belenko, S., Knight, D., Wasserman, G. A., Dennis, M. L., Wiley, T., Taxman, F. S., . . . Sales, J. (2017). The juvenile justice behavioral health services cascade: A new framework for measuring unmet substance use treatment services needs among adolescent offenders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 74, 80–91.

- Burke, A. S., Carter, D. E., Fedorek, B., Morey, T. L., Rutz-Burri, L., & Sanchez, S. K. (2019). Introduction to the American criminal justice system. Retrieved from https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/ccj230/front-matter/introduction/

- Copeland, W. E., Miller-Johnson, S., Keeler, G., Angold, A., & Costello, E. J. (2007). Childhood psychiatric disorders and young adult crime: A prospective, population-based study. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(11), 1668–75.

- Cuellar, A. E., Markowitz, S., & Libby, A. M. (2004). Mental health and substance abuse treatment and juvenile crime. The Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 7(2), 59–68.

- Elkington, K. S., Lee, J., Brooks, C., Watkins, J., & Wasserman, G. A. (2020). Falling between two systems of care: Engaging families, behavioral health, and the justice systems to increase uptake of substance use treatment in youth on probation. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 112, 49–59.

- Englund, M. M., Egeland, B., Oliva, E. M., & Collins, W. A. (2008). Childhood and adolescent predictors of heavy drinking and alcohol use disorders in early adulthood: A longitudinal developmental analysis. Addiction, 103(Suppl. 1), 23–5.

- Fisher, J. H., Becan, J. E., Harris, P. W., Nager, A., Baird-Thomas, C., Hogue, A., . . . JJ-TRIALS Cooperative (2018). Using goal achievement training in juvenile justice settings to improve substance use services for youth on community supervision. Health & Justice, 6(1), 10.

- Henggeler, S. W., Clingempeel, W. G., Bronidon, M. J., & Pickrel, S. G. (2002). Four-year follow-up of multisystemic therapy with substance-abusing and substance-dependent juvenile offenders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(7), 868–74.

- Hoeve, M., McReynolds, L. S., Wasserman, G. A., & McMillan, C. (2013). The influence of mental health disorders on severity of reoffending in juveniles. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 40(3), 289–301.

- Hoeve, M., McReynolds, L. S., & Wasserman, G. A. (2014). Service referral for juvenile justice youths: Associations with psychiatric disorder and recidivism. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 41(3), 379–89.

- Johnson, T. P., Cho, Y. I., Fendrich, M., Graf, I., Kelly-Wilson, L., & Pickup, L. (2004). Treatment need and utilization among youth entering the juvenile corrections system. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 26(2), 117–28.

- Kann, L., McManus, T., Harris, W. A., Shanklin, S. L., Flint, K. H., Queen, B., . . . Ethier, K. A. (2018). Youth risk behavior surveillance – United States, 2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(8), 1–114.

- Kataoka, S. H., Zhang, L., & Wells, K. B. (2002). Unmet need for mental health care among US children: Variation by ethnicity and insurance status. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(9), 1548–55.

- Loeber, R., Farrington, D. P., & Waschbusch, D. A. (1999). Serious and violent juvenile offenders. In R. Loeber, & D. P. Farrington (Eds.), Serious and violent juvenile offenders: Risk factors and successful interventions (pp. 13–30). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Loeber, R., Pardini, D., Homish, D. L., Wei, E. H., Crawford, A. M., Farrington, D. P., . . . Rosenfeld, R. (2005). The prediction of violence and homicide in young men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(6), 1074–88.

- Loeber, R., Stouthamer-Loeber, M., Van Kammen, W., & Farrington, D. P. (1991). Initiation, escalation, and desistance in juvenile offenders and their correlates. The Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology, 82(1), 36–82.

- McClelland, G. M., Elkington, K. S., Teplin, L. A., & Abram, K. M. (2004). Multiple substance use disorders in juvenile detainees. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(10), 1215–24.

- Merikangas, K. R., He, J. -P., Burstein, M., Swanson, S. A., Avenevoli, S., Cui, L., . . . Swendsen, J. (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication–adolescent supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980–9.

- Novins, D. K., Duclos, C. W., Martin, C., Jewett, C. S., & Manson, S. M. (1999). Utilization of alcohol, drug, and mental health treatment services among American Indian adolescent detainees. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(9), 1102–8.

- Stone, A. L., Becker, L. G., Huber, A. M., & Catalano, R. F. (2012). Review of risk and protective factors of substance use and problem use in emerging adulthood. Addictive Behaviors, 37(7), 747–75.

- Swift, W., Coffey, C., Carlin, J. B., Degenhardt, L., & Patton, G. C. (2008). Adolescent cannabis users at twenty-four years: Trajectories to weekly regular use and dependence in young adulthood. Addiction, 103(8), 1361–70.

- Teplin, L. A., Abram, K. M., McClelland, G. M., Dulcan, M. K., & Mericle, A. A. (2002). Psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59(12), 1133–43.

- Wasserman, G. A., McReynolds, L. S., Ko, S. J., Katz, L. M., & Carpenter, J. R. (2005). Gender differences in psychiatric disorders at juvenile probation intake. American Journal of Public Health, 95(1), 131–7.

- Wasserman, G. A., McReynolds, L. S., Whited, A. L., Keating, J. M., Musabegovic, H., & Huo, Y. (2008). Juvenile probation officers’ mental health decision making. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 35(5), 410–22.

- Wasserman, G. A., McReynolds, L. S., Musabegovic, H., Whited, A. L., Keating, J. M., & Huo, Y. (2009). Evaluating project connect: Improving juvenile probationers’ mental health and substance use service access. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 36(6), 393–405.

- Winters, K. C., & Lee, C. -Y. S. (2008). Likelihood of developing an alcohol and cannabis use disorder during youth: Association with recent use and age. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 92(1–3), 239–47.

Editor’s Note: This article was adapted from an article by the same authors previously published in the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment (JSAT). This article has been adapted as part of Counselor’s memorandum of agreement with JSAT. The following citation provides the original source of the article:

- Elkington, K. S., Lee, J., Brooks, C., Watkins, J., & Wasserman, G. A. (2020). Falling between two systems of care: Engaging families, behavioral health, and the justice systems to increase uptake of substance use treatment in youth on probation. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 112, 49–59.

Maggie E. Ryan, MPH

Maggie E. Ryan, MPH, is currently a project director of two implementation science studies at the Center for Promotion of Behavioral Health in Youth Justice (CPBHYJ) at Columbia University/New York State Psychiatric Institute. Both projects focus on developing, implementing, and evaluating processes to link juvenile- and criminal-justice involved individuals to the treatment they need.

Jaqueline Lee, MS, RN

Jaqueline Lee, MS, RN, completed her master of science in nursing at Columbia University School of Nursing. She is currently a first-year DNP student at Columbia University School of Nursing.

Catherine Brooks, MA

Catherine Brooks, MA, received her MPH from Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, with a focus on epidemiology and social determinants of health. She is currently a clinical research associate at IQVIA.

Jillian Watkins, MSc

Jillian Watkins, MSc, completed her master’s in health services research at the University of Toronto. She most recently served as interim executive director at HIV/AIDS Resources and Community Health. She currently provides consulting to AIDS Service Organizations in Ontario, Canada.

Katherine S. Elkington, PhD

Katherine S. Elkington, PhD, is a licensed clinical psychologist, an associate professor of clinical psychology (in psychiatry) at Columbia University, and a research scientist at the New York State Psychiatric Institute. She also serves as the codirector of Center for the Promotion of Mental Health in Juvenile Justice (CPMHJJ). Dr. Elkington has over fifteen years of research experience in justice settings.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.