Twelve Step facilitative therapy refers to a structured form of treatment that seeks to increase attendance and involvement with Twelve Step mutual support groups. The common elements of these treatments are introducing individuals to the Twelve Step program and encouraging active participation. Typically, this takes the form of introducing and discussing the first three Steps, and emphasizing becoming active by working the Steps and being involved in meetings. An intervention of this type is the Project MATCH TSF (Twelve Step Facilitation) treatment, consisting of twelve weekly individual sessions or ten individual and two conjoint sessions with a significant other. Quite a different approach is the group intervention Making Alcoholics Anonymous Easier (MAAEZ; Kaskutas, Subbaraman, Witbrodt, & Zemore, 2009), which seeks to overcome potential barriers to participation and explain how to make use of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA). Yet another approach uses an intensive referral and “buddy system” to engage individuals in their first meetings (Timko, DeBenedetti, & Billow, 2006). Typically counselors assist their patient in connecting with a volunteer active self-help group member who agrees to meet the patient at a meeting.

There is strong research support for the ability of these therapies to increase attendance and active involvement in Twelve Step fellowships, improve drinking or other substance use outcomes, and have long-lasting effects (Carroll, Nich, Ball, McCance, & Rounsaville, 1998; Carroll et al., 2000; Crits-Christoph et al., 1999; Project MATCH Research Group, 1997; Timko et al., 2006; Timko & DeBenedetti, 2007). In addition, a number of studies have found that greater exposure through greater attendance of Twelve Step facilitative treatments is associated with more involvement in Twelve Step or other mutual support groups as well as improved substance use outcomes. For example, in a study of MAAEZ Kaskutas and colleagues (2009) found a dose-response; the group that completed 0–1 sessions had a self-reported abstinence rate of 70 percent from both alcohol and drugs at the twelve-month follow-up point, whereas those completing three sessions had a rate of almost 80 percent, and those completing all six sessions had a rate of 90 percent. In a population with substance use disorder (SUD) co-occurring with a psychiatric disorder, Timko, Sutkowi, Cronkite, Makin-Byrd, and Moos (2011) found that a higher dose of intensive referral was associated with attending at least one dually-focused mutual help group (DFGs), greater readiness to attend DFGs, attending more substance-focused groups (SFGs), and being more involved in SFGs.

From 2008–2010, the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network (CTN) conducted an efficacy trial of Twelve Step facilitative treatment in ten community treatment programs (CTPs) located in eight US states. The study compared Stimulant Abuser Groups to Engage in Twelve Step (STAGE-12), an intervention consisting of five group sessions adapted from the Project MATCH TSF combined with three individual sessions adapted from the intensive referral program intervention (Timko et al., 2006) and the AA Bridging the Gap program (AA, 1991), integrated into standard treatment, to standard treatment alone, among stimulant users in intensive outpatient treatment. The main results, reported by Donovan and colleagues (2013), revealed that those receiving STAGE-12 were more likely to be abstinent during treatment than those in standard treatment alone, but among those who were not abstinent, STAGE-12 participants used stimulants on more during-treatment days.

The Study

The purpose of this report was to examine whether level of exposure to a Twelve Step facilitative therapy is related to stimulant users’ treatment outcomes such as self-reported stimulant use, self-reported nonstimulant use, biological measures of drug use or self-reported attendance and active involvement in Twelve Step meetings. The parent study provided the opportunity to examine whether those with a high level of exposure to the STAGE-12 intervention differed in their treatment outcomes from those with less exposure.

Patients in the parent study were randomly assigned to one of two study conditions: the STAGE-12 intervention integrated into standard treatment or standard treatment alone. Because intervention exposure was measured only for the STAGE-12 participants, this report looks only at those 234 participants randomly assigned to STAGE-12. Assessments took place before treatment (baseline) and at thirty (mid-treatment), sixty (end-of-treatment), ninety (first follow-up), and 180 days (last follow-up) following randomization.

STAGE-12 was integrated into standard treatment; that is, STAGE-12 sessions replaced treatment sessions that would otherwise have been received (see Donovan et al., 2011). However, STAGE-12 participants did receive portions of the CTP’s regular treatment that were not replaced:

The ten selected CTPs provided a mean of 9.6 hours of treatment per week (standard deviation [SD] = 2.85, ranging from six to fifteen hours) for an average of 13.5 weeks (SD = 5.12, ranging from 7.5 to twenty-four weeks). During the course of the study patients in participating CTPs typically attended three group sessions and one individual session per week (Donovan et al., 2013, p. 105).

Of the 234 participants assigned to the Stage-12 intervention, 62 percent were women, 6.4 percent reported Hispanic/Latino ethnicity, 46.2 percent reported Caucasian race, and 37.6 percent reported Black/African American race. They averaged 38.2 years of age (SD = 10.0) and 12.2 years of education (SD = 1.7). Thirty-four percent were unemployed, and only 15.5 percent were currently married. A majority (72.7 percent) met DSM-IV criteria for current cocaine, 33.8 percent for methamphetamine, 6.8 percent for amphetamine, and 44.9 percent for alcohol dependence. About one fifth (22.2 percent) were legally mandated to attend treatment.

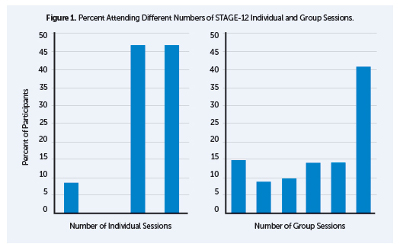

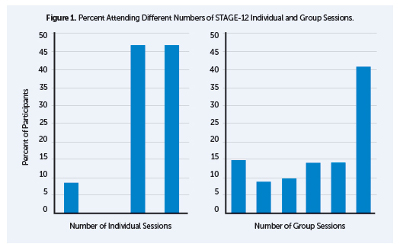

While designing the STAGE-12 intervention, the investigators identified an adequate dose of the intervention as having attended two or more individual sessions plus three or more group sessions. Selection of this criterion was based on the experience of the investigators and treatment program representatives with interventions of this length and type and the desire to identify a level of exposure that would be considered therapeutic. In this report, patients meeting this criterion are referred to as having a high level of exposure, and those with less attendance as having low exposure to STAGE-12. Rates of attendance at STAGE-12 individual and group sessions are shown in Figure 1. Out of the 234 people assigned to STAGE-12, the number of people meeting the criterion for therapeutic (high) exposure, was 158 (67.5 percent). Of these, eighty-eight individuals (56 percent of those with high exposure) attended all eight intervention sessions. However, of the 234 assigned to STAGE-12, thirty (12.8 percent) did not complete at least one post-baseline assessment and were excluded from this report. Within the remaining sample of 204 individuals, 157 (77 percent) met criteria for high exposure to STAGE-12. The fact that only one of the thirty excluded participants met criteria for high exposure indicates that high-exposure participants are overrepresented and those with low exposure underrepresented in the current report.

Methods, Tools, and Results

Although outpatient SUD treatment is thought to be characterized by high dropout rates and low rates of treatment completion, exposure to STAGE-12 treatment was relatively high for this eight-session intervention embedded within intensive outpatient treatment as usual. Over two thirds of patients met criteria for high exposure to the STAGE-12 intervention, and there was relatively low early attrition; only 8 percent failed to attend any sessions. These results compare favorably with other studies of short-term outpatient treatment with stimulant users (e.g., Aharonovich et al., 2006; Covi, Hess, Schroeder & Preston, 2002).

Patient satisfaction with treatment is one possible basis for high levels of exposure. STAGE-12 participants completed the participant satisfaction survey (PSS) at the end of the STAGE-12 treatment phase. Two subscale scores were calculated: total satisfaction score (six items) and total benefit score (two items). In addition, participants rated eight parts of the STAGE-12 program on whether each part occurred and how helpful it was. High exposure participants rated the STAGE-12 intervention as more beneficial and they reported greater overall satisfaction with it than did those who attended less. High-exposure participants rated all eight program elements as helpful. The program elements are as follows:

- Counselor

- Group meetings

- Individual sessions

- Better understanding of Twelve Step programs

- Assignments/recovery tasks

- Encouragement to get involved in Twelve Step

- Arrange to have outside Twelve Step member help

- Attend Twelve Step meetings in the community

The association between patients’ exposure to STAGE-12 and their substance use outcomes was measured using both self-report and urine testing. Number of days of self-reported stimulant drug use and nonstimulant drug use came from a timeline follow-back procedure, the Substance Use Calendar (SUC), collected at baseline, mid-treatment (thirty-day), end-of-treatment (sixty-day), first follow-up (ninety-day), and last (180-day) follow-up. The Addiction Severity Index (ASI) Drug Use Composite and Alcohol Use Composite scores (ranging from 0–1) were used to measure substance use problems. At each assessment point, participants provided a urine sample that was tested for the presence of a stimulant drug (cocaine, amphetamines or methamphetamine).

We examined both “any use” versus “no use” of stimulant and nonstimulant drugs and the number of days of use among those reporting any use. Regarding their stimulant use, patients achieving high exposure to STAGE-12 compared with those with less exposure, demonstrated:

- Higher odds of self-reported abstinence from stimulant drug use during, and extending to two months after the end of, treatment

- Among those reporting any stimulant use, fewer days of stimulant drug use during the STAGE-12 treatment period

- Lower likelihood of stimulant-positive urines during, and at one month following, treatment

High exposure to STAGE-12 was also associated with a greater likelihood of self-reported abstinence from nonstimulants in the first thirty days of treatment and, among those reporting any nonstimulant use, fewer days of use during this same period.

Because participants determined their own level of STAGE-12 exposure, there are a number of possible other-than-causal explanations of the relationship between exposure and substance use outcomes. One likely explanation is that individuals who begin with greater motivation to change their drug use are both more likely to remain involved in the intervention and less likely to use stimulants. Confidence in ability to remain abstinent could also be related to treatment attendance. Motivation and readiness were assessed with two measures, the fifteen-item Survey of Readiness for Alcoholics Anonymous Participation (SYRAAP; Kingree et al., 2006), which measures ambivalence toward, and readiness to engage in, Twelve Step activities, and the Stages of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale, version 8 Drugs (SOCRATES-8D; Miller & Tonigan, 1996), a measure of readiness to change drug use. Participants also completed the Drug Taking Confidence Scale – 8 (DTCQ8) a measure of confidence in one’s ability to cope with high risk situations for drug use (Sklar & Turner, 1999). Whether or not a patient reported being mandated to participate in this episode of SUD treatment was also considered as a proxy for internal versus external motivation.

Motivation level at the beginning of treatment, measured by the SOCRATES and the SYRAAP, was not related to STAGE-12 exposure. Having been mandated to treatment was also unrelated to exposure. At first glance the DTCQ total score appeared to be related to exposure, in that as one’s relapse prevention confidence increased, so did the odds of high exposure. However, when baseline DTCQ score was controlled in analyses of substance use outcomes, it had no effect on the relationship between exposure and substance use. These findings suggest that differences in initial level of motivation or confidence do not explain the study’s findings.

The STAGE-12 intervention was designed to reduce substance use by increasing patients’ involvement in Twelve Step meetings and activities. To examine whether greater exposure to STAGE-12 was associated with greater Twelve Step involvement, participants reported their own attendance at Twelve Step mutual support meetings on the SUC. They also completed the Self-Help Activities Questionnaire (SHAQ; Weiss et al., 1996) from which three outcome variables were derived:

- Maximum number of days of self-reported speaking at AA, NA (Narcotics Anonymous), CA (Cocaine Anonymous) or CMA (Crystal Meth Anonymous) meetings

- Maximum number of days of self-reported duties at AA, NA, CA or CMA meetings

- Number of other self-help activities in which the participant engaged indicating how many of the following were reported:

- Met with one or more AA/NA/CA/CMA members outside a meeting

- Met with sponsor outside meeting

- Phoned sponsor

- Received at least one phone call from sponsor

- Received at least one phone call from other members

- Read Twelve Step literature for at least five minutes

High-exposure participants had the following characteristics:

- Lower odds of not attending meetings both during treatment and at all the follow-up assessments

- Among those with any meeting attendance, more days of attendance during treatment and in the thirty days after the end of treatment

- A greater number of days of self-reported duties at meetings both during, and for thirty days following, treatment

Regarding the number of types of Twelve Step activities, the two exposure groups differed significantly at every time point, including baseline, indicating that those with high exposure began the study with greater meeting involvement, and the initial difference between those who met high exposure criteria and those who did not was maintained.

Unfortunately, we can’t conclude that STAGE-12 exposure produced these better short-term outcomes, as the reverse could very well be true; individuals struggling with abstinence during treatment are known by clinicians to be less likely to comply with treatment. In addition, continuing to use drugs after entering treatment is likely to influence the degree to which a person is a reliable attender or active participant in Twelve Step meetings.

Participants who attended the STAGE-12 intervention at a high level showed evidence at the study outset of greater Twelve Step involvement, and to a great extent, they maintained a higher rate of involvement over time. From the primary outcome analysis for this study (Donovan et al., 2013), as a group, STAGE-12 participants had greater odds of self-reported abstinence, but also higher rates of during-treatment drug use among those not abstinent than among those not randomized to STAGE-12. Together, both analyses suggest that STAGE-12 might influence treatment outcome by supporting already existing Twelve Step meeting involvement over time.

Limitations

This report examined only individuals initiating treatment in CTN community treatment programs (CTPs) who volunteered to participate in a randomized study of STAGE-12. These CTPs may represent a select set of programs in that they have agreed to ongoing involvement in research and may have more readiness to implement treatment innovations than do other programs. However, the selection process for the STAGE-12 study involved purposefully recruiting three research-naïve sites from among the many programs with membership in the CTN. Likewise, patients who volunteer for such a study may be more interested in facilitation of their involvement in Twelve Step programs or may be generally more motivated to do well in treatment. Thus, the results likely do not apply equally to all patients in all types of programs. However, similar limitations can be applied to most SUD treatment studies, and every effort was made in these clinics to recruit all potentially eligible patients.

Within the STAGE-12 condition, participants self-selected into exposure groups, and more of those with low exposure failed to return for follow-up assessment. This resulted in underrepresentation of low exposure patients in this report. It is not known what effect this might have on the results.

Two additional limitations, common to a number of SUD treatment studies, are a reliance on self-report for most outcomes and limited use of urine drug screens to validate this report. These screens were done at a limited number of assessment points, known in advance to the participants. Regarding these two limitations, all self-report and urine screen data were kept confidential; they were not reported to staff at the treatment programs, and there were no negative consequences for reporting substance use or providing a positive UDS.

Discussion

Beginning Twelve Step involvement early in treatment has been found to be beneficial (Moos & Moos, 2004). Although a majority of community-based treatment programs either encourage or require Twelve Step attendance, few have a standard program for systematically orienting patients to Twelve Step involvement and promoting an understanding of Twelve Step principles and philosophy as well as attendance and active involvement in meetings (Caldwell, 1999; Humphreys & Moos, 2007; Humphreys et al., 2004).

Manual-based interventions, such as STAGE-12, provide programs with a method of standardizing this type of orientation and encouragement. The intervention highlights the potentially powerful benefits of Twelve Step involvement, particularly for patients with initial reservations. Furthermore, for those who are hesitant to go to Twelve Step meetings, it provides active support for attending a first meeting, via linkage to a community volunteer.

The current study demonstrates that it is feasible to interest people entering intensive outpatient treatment in a Twelve-Step-oriented intervention and that individuals who agree to participate can be retained in the intervention at relatively high rates. In this particular study, the STAGE-12 intervention was embedded within standard treatment for those agreeing to participate and assigned to STAGE-12, mirroring what would likely be the case in programs adopting STAGE-12. Thus, attending STAGE-12 was part of meeting requirements for completing treatment. About 20 percent of participants were court-mandated to treatment, but others may also have had external pressures related to satisfying program requirements. In addition, no association between being mandated to treatment and level of STAGE-12 exposure was found. Under these conditions, the current study demonstrates feasibility in that when this intervention is part of treatment, patients do attend.

The declining effects of STAGE-12 exposure across follow-up time points suggest a possible need for booster group or individual sessions that would reinforce lessons learned in the earlier sessions. This clinical approach fits within a framework of chronic disease management in which single episodes of treatment are not expected to have long-lasting effects.

Because patients determined their own exposure to STAGE-12, this study cannot demonstrate that attending more STAGE-12 sessions caused increased Twelve Step involvement or reduced stimulant and nonstimulant drug use. What does it mean, then, that treatment exposure and outcomes are related to each other, and this is not, in this study, accounted for by patient motivation or abstinence self-efficacy? One interpretation shared by both clinicians and researchers is that both exposure (e.g., sessions attended or weeks retained) and patient behavior outside of treatment (e.g., substance use or Twelve Step meeting attendance) are related indications of outcome, or how a patient is doing in treatment. Will simply working to increase attendance result in greater abstinence? Perhaps not, but early missed sessions may signal a patient who is in need of adjustments to the treatment plan. In this report, more satisfaction with STAGE-12 was associated with higher exposure. In a separate analysis of STAGE-12 data (Campbell et al., 2015), both therapeutic alliance and counselor competence were significantly associated with treatment retention. These results point to the importance of counselor training and of ongoing monitoring of the counselor-patient relationship and patient satisfaction.

A number of programs involved in the CTN trial of STAGE-12 chose to incorporate all or parts of the STAGE-12 intervention into their programs at the conclusion of the trial. Some programs incorporated only the group sessions, while retaining their standard treatment for the individual sessions. Several program directors indicated that implementation of the intensive referral posed the greatest challenge, because it necessitated additional coordination with Twelve Step volunteers in the community. Research on implementation of Twelve Step facilitative treatments would help to identify organizational, staffing, intervention, and policy context variables that act as facilitators or barriers to adoption.

Acknowledgements: This report was supported by a series of grants from NIDA as part of the Cooperative Agreement on National Drug Abuse Treatment CTN: Appalachian/Tri-States Node (U10DA20036), Florida Node Alliance (U10DA13720), Ohio Valley Node (U10DA13732), Oregon Node (U10DA13036), Pacific Region Node (U10DA13045), Pacific Northwest Node (U10DA13714), Southern Consortium Node (U10DA13727), and Texas Node (U10DA20024). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIDA.

We would like to express our appreciation to the patients and the administrative, clinical, and research staff of the 10 CTPs that participated in the present study: Center for Psychiatric & Chemical Dependency Services, Pittsburgh, PA; ChangePoint, Inc. Portland, OR; Dorchester Alcohol & Drug Commission, Summerville, SC; Evergreen Manor, Everett, WA; Gateway Community Services, Jacksonville, FL; HinaMauka, Kaneohe, HI; Maryhaven, Columbus, OH; Nexus Recovery Center, Dallas, TX; Recovery Centers of King County, Seattle, WA; and Willamette Family Treatment Services, Eugene, OR.

References

Aharonovich, E., Hasin, D. S., Brooks, A. C., Liu, X., Bisaga, A., & Nunes, E. V. (2006). Cognitive deficits predict low treatment retention in cocaine dependent patients. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 81(3), 313–22.

Alcoholics Anonymous. (1991). Bridging the gap between treatment and AA through temporary contact programs. New York, NY: Alcoholics Anonymous World Services.

Caldwell, P. E. (1999). Fostering client connections with Alcoholics Anonymous: A framework for social workers in various practice settings. Social Work in Health Care, 28(4), 45–61.

Campbell, B. K., Guydish, J., Le, T., Wells, E. A., & McCarty, D. (2015). The relationship of therapeutic alliance and treatment delivery fidelity with treatment retention in a multisite trial of twelve step facilitation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29(1), 106–13.

Carroll, K. M., Nich, C., Ball, S. A., McCance, E., & Rounsaville, B. J. (1998). Treatment of cocaine and alcohol dependence with psychotherapy and disulfiram. Addiction, 93(5), 713–27.

Carroll, K. M., Nich, C., Ball, S. A., McCance, E., Frankforter, T. L., & Rounsaville, B. J. (2000). One-year follow-up of disulfiram and psychotherapy for cocaine-alcohol users: sustained effects of treatment. Addiction, 95(9), 1335–49.

Covi, L., Hess, J. M., Schroeder, J. R., & Preston, K. L. (2002). A dose response study of cognitive behavioral therapy in cocaine abusers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 23(3), 191–7.

Crits-Christoph, P., Siqueland, L., Blaine, J., Frank, A., Luborsky, L., Onken, L. S., . . . Beck, A. T. (1999). Psychosocial treatments for cocaine dependence: Results of the NIDA cocaine collaborative study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56(6), 493–502.

Donovan, D. M., Daley, D. C., Brigham, G. S., Hodgkins, C. C., Perl, H. I., & Floyd, A. S. (2011). How practice and science are balanced and blended in the NIDA clinical trials network: The bidirectional process in the development of the STAGE-12 protocol as an example. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 37(5), 408–16.

Donovan, D. M., Daley, D. C., Brigham, G. S., Hodgkins, C. C., Perl, H. I., Garrett, S. B., . . . Zammarelli, L. (2013). Stimulant abuser groups to engage in twelve step: A multisite trial in the National Institute on Drug Abuse clinical trials network. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 44(1), 103–14.

Humphreys, K., & Moos, R. H. (2007). Encouraging posttreatment self-help group involvement to reduce demand for continuing care services: Two-year clinical and utilization outcomes. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research, 31(1), 64–8.

Humphreys, K., Wing, S., McCarty, D., Chappel, J., Gallant, L., Haberle, B., . . . Weiss, R. (2004). Self-help organizations for alcohol and drug problems: Toward evidence-based practice and policy. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 26(3), 159–65.

Kaskutas, L. A., Subbaraman, M. S., Witbrodt, J., & Zemore, S. E. (2009). Effectiveness of making Alcoholics Anonymous easier: A group format twelve step facilitation approach. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 37(3), 228–39.

Kingree, J. B., Simpson, A., Thompson, M., McCrady, B. S., Tonigan, J. S., & Lautenshlager, G. (2006). The development and initial evaluation of the survey of readiness for alcoholics anonymous participation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 20(4), 453–62.

Miller, W. R., & Tonigan, J. S. (1996). Assessing drinkers’ motivation for change: The stages of change readiness and treatment eagerness scale (SOCRATES). Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 10(2), 81–9.

Moos, R. H., & Moos, B. S. (2004). Long-term influence of duration and frequency of participation in alcoholics anonymous on inidividuals with alcohol use disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(1), 81–90.

Project Match Research Group. (1997). Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 58(1), 7–29.

Sklar, S. M., & Turner, N. E. (1999). A brief measure for the assessment of coping self-efficacy among alcohol and other drug users. Addiction, 94(5), 723–9.

Timko, C., & DeBenedetti, A. (2007). A randomized controlled trial of intensive referral to twelve step self-help groups: One-year outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 90(2–3), 270–9.

Timko, C., DeBenedetti, A., & Billow, R. (2006). Intensive referral to twelve step self-help groups and six-month substance use disorder outcomes. Addiction, 101(5), 678–88.

Timko, C., Sutkowi, A., Cronkite, R. C., Makin-Byrd, K., & Moos, R. H. (2011). Intensive referral to twelve step dual-focused mutual-help groups. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 118(2–3), 194–201.

Weiss, R. D., Griffin, M. L., Najavits, L. M., Hufford, C., Kogan, J., Thompson, H. J., . . . Siqueland, L. (1996). Self-help activities in cocaine dependent patients entering treatment: Results from NIDA collaborative cocaine treatment study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 43(1–2), 79–86.

Editor’s Note: This article was adapted from an article by the same authors previously published in the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment (JSAT). This article has been adapted as part of Counselor’s memorandum of agreement with JSAT. The following citation provides the original source of the article:

Wells, E. A., Donovan, D. M., Daley, D. C., Doyle, S. R., Brigham, G., Garrett, S. B., . . . Walker, R. (2014). Is level of exposure to a twelve step facilitation therapy associated with treatment outcome? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 47(4), 265–74.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.