Share

It may come as a surprise to some that the major threat to the health of clients with behavioral health issues is not the underlying mental health condition or the use of substances such as alcohol, cocaine, or heroin. As serious as those problems are, they are not the chief killer of persons with behavioral health issues. Rather, the adverse health consequences of tobacco use are the main culprits. Currently we are in the midst of a culture change, as behavioral health treatment evolves from a situation where cigarette smoking was either tolerated as the lesser of evils or even encouraged as a way to reward “good behavior,” to one in which smoking cessation is viewed as a major treatment goal. This article will review why that is so and what behavioral health treatment providers can do to help preserve the health of their clients.

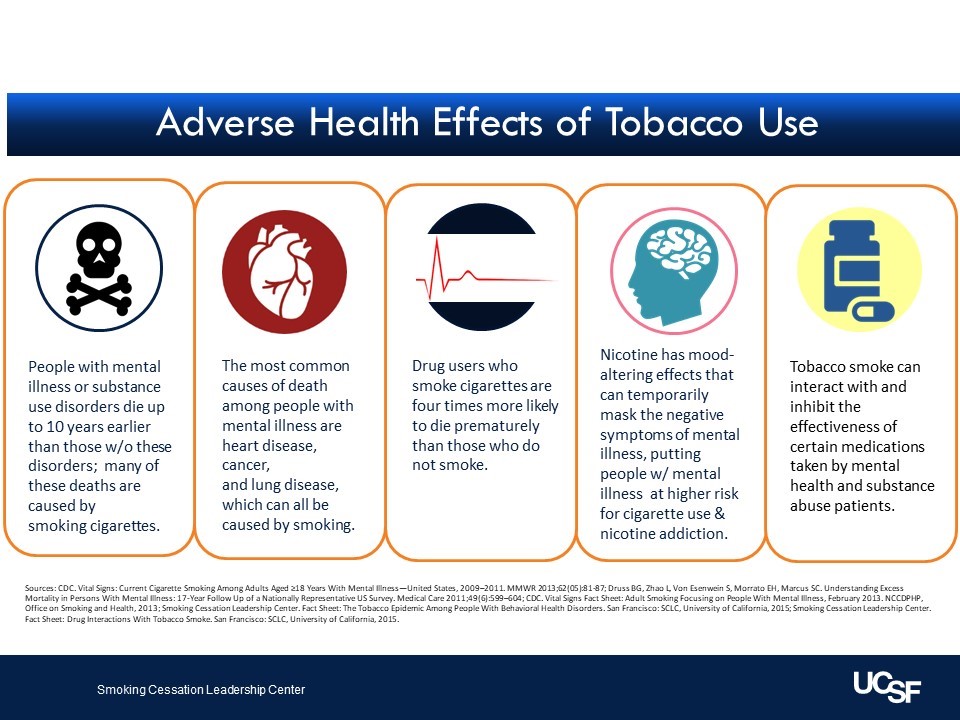

Figure 1 briefly summarizes the health consequences of tobacco use and explains why it is important to help smokers quit.

Figure 1

The goal of all behavioral health treatment providers is to improve the health and wellness of their clients. A key component of that improvement should be to support clients in leading healthier lives protected from exposure to tobacco products. That means ensuring both that they are not using tobacco and that they live in an environment free of secondhand smoke. Crucial to health and wellness is living free from the burden of tobacco use.

Despite what many think, smoking remains the leading cause of premature, preventable death among adults in the United States (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2014). And although smoking rates among adults are now at a modern low of 14 percent, smoking has become concentrated among vulnerable populations (Creamer et al., 2019). For those with behavioral health conditions, the toll is quite great. Targeted marketing, pressure from the burden of behavioral health conditions, stigma, and little to no access to cessation services are just some of the reasons this population is smoking at a rate that is two to three times greater than that of the general population.

Figure 2

As a result, this population is far more likely to die of smoking-related diseases than from causes related to their mental health or substance use disorders (SUDs). These deaths cut over ten years from their life spans and additional burdens are also created, including the disability from such conditions as chronic lung disease, the financial toll from having to purchase tobacco products, and the stigma that arises today from tobacco use.

Behavioral health agencies have a unique opportunity to improve the health and wellness of their clients by creating tobacco-free environments where tobacco use is prohibited and cessation treatment is promoted and well supported. This article serves to provide a current view of smoking among the behavioral health population and what behavioral health providers and facilities can do to address tobacco use among this community.

Smoking in the Behavioral Health Community

While smoking rates in the general population have decreased over the last decades (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2014), this is not the case for people with behavioral health conditions. In spite of measures that have greatly reduced smoking in general—clean indoor air laws, higher cigarette taxes, and effective media campaigns—the behavioral health population continues to smoke at very high rates, putting them at increased risk of tobacco-related disease and death. There are about seven thousand chemicals in tobacco smoke, many of which can cause cancer, and many others can cause cardiovascular disease and other health problems (ALA, 2019).

In California the adult smoking rate in 2017 was 10.1 percent, well below the national rate of 14 percent (Vuong, Zhang, & Roeseler, 2019). This was in large part due to the state’s groundbreaking and comprehensive approach to tobacco control. However, adults identifying as having psychological distress (26.7 percent) still smoke at rates far higher than others, and males with psychological distress (33.5 percent) smoke at more than three times the statewide rate (Vuong et al., 2019). Smoking is also more common among those who have SUDs (SCLC, 2019). Additionally, in California those who report binge drinking smoke at nearly three times the rate of those who do not binge drink (SCLC, 2019).

Smoking Cessation Services in Behavioral Health Treatment Facilities

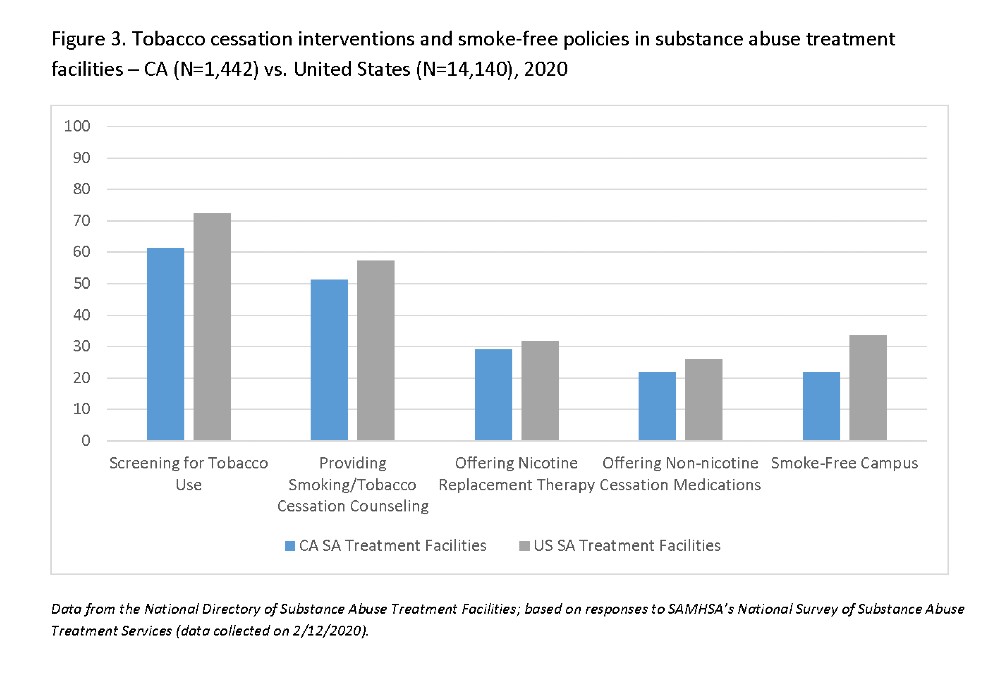

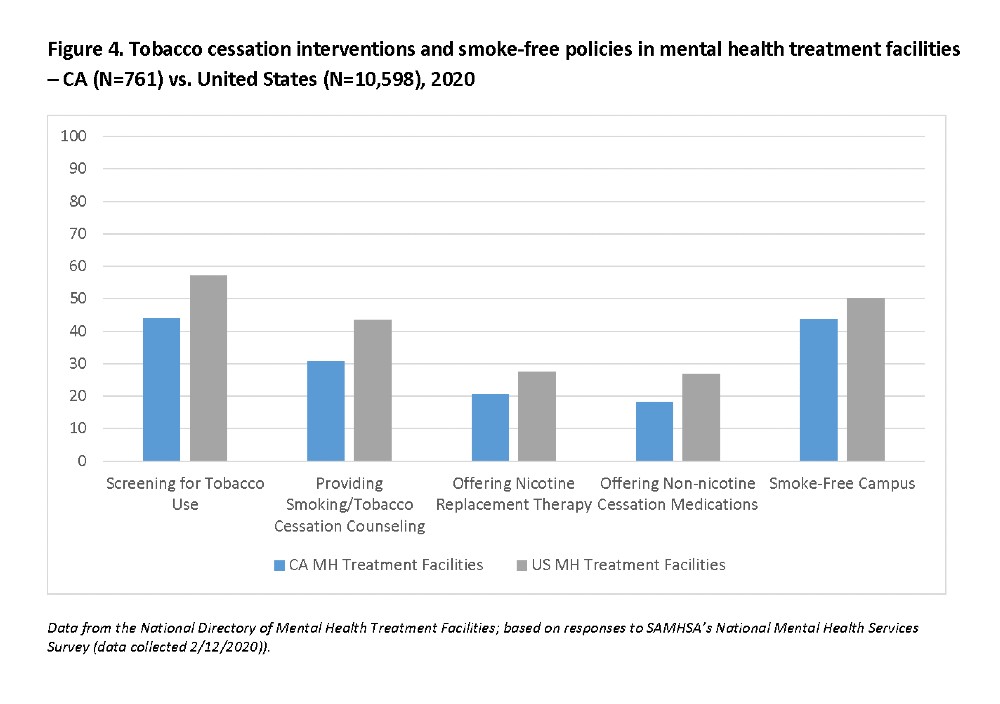

Rates of addressing tobacco use are lagging in behavioral health treatment settings. According to a 2018 article, in substance use treatment facilities California is ranked ninth lowest in the nation for tobacco use screening, eighteenth lowest in providing cessation counseling, tenth lowest in utilization of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), and fourth lowest in percentage of smoke-free campuses (Marynak et al., 2018). These are puzzling statistics, because in most other respects California has led the nation in developing and executing strategies to help smokers quit and to discourage young people from starting to smoke. It appears as though the behavioral health treatment community has been absent from these efforts.

Figure 3

Figure 4

Dispelling the Myths

Contrary to popular belief, people with behavioral health conditions want to quit smoking, want information on cessation services and resources, and most importantly, can successfully quit using tobacco. One study found that 52 percent of cocaine users, 50 percent of alcoholics, and 42 percent of heroin users were interested in quitting smoking at the time they began treatment for their other addictions (Sullivan & Covey, 2002).

This is in contrast to the assumptions of many treatment specialists: that their clients need to keep smoking while they grapple with their behavioral health conditions. Although smokers with behavioral health conditions are slightly less likely to succeed in a quit attempt than the general population, many are able to do so, especially when helped by clinicians.

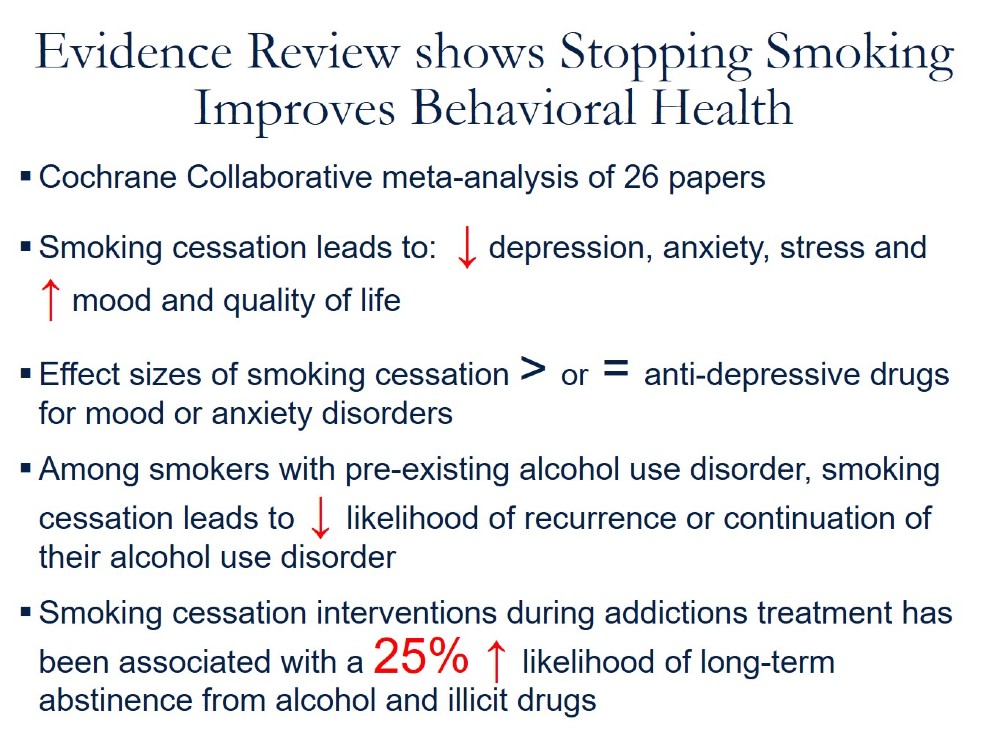

Another myth is that if people with behavioral health conditions stop smoking, their underlying mental illnesses or addictions will worsen. In fact, the opposite is true. There is mounting evidence that clients who receive concurrent cessation services for tobacco use while in treatment are more likely to reduce their use of alcohol and other drugs, have fewer psychiatric symptoms, and enjoy better behavioral health treatment outcomes overall (Taylor et al., 2014).

Figure 5

Treatment

Treating people with behavioral health conditions follows similar clinical guidelines as for people in the general population. This treatment aims at reducing cravings for the very addictive drug nicotine, which is such an important reason why smoking cessation proves so difficult. Treatment is also aimed at changing the behavioral cues that trigger smoking as well as providing motivations to quit.

Smoking cessation treatment consists of skilled counseling coupled with the use of FDA-approved smoking cessation medications. These medications include five forms of NRT as well as two oral medications.

The five forms of NRT include the patch, gum, lozenge, nasal spray, and inhaler. The first three may be purchased over the counter, while the nasal spray and inhaler require prescriptions. The patch provides long-acting nicotine release, which reduces the desire for nicotine intake, while the short-acting versions provide bursts of nicotine in order to respond to cravings. It is common to pair the long-term therapy of a patch with short-acting NRT such as the gum or lozenge.

The two oral medications are bupropion, an antidepressive drug that reduces the craving for nicotine, and varenicline, a nicotine receptor partial agonist. Bupropion, also known by its brand name Wellbutrin, is often used in combination with short- and/or long-acting NRT. Varenicline (brand name Chantix), has the highest reported quit rates of any of the approved medications (Burke, Hays, & Ebbert, 2016). There have been some reported trials of pairing it with NRT (Burke et al., 2016).

When varenicline first came on the market there were some reports of suicidal ideation and actual suicide events, prompting the FDA to put a black-box warning on the drug and to conduct more research on its safety. A subsequent large trial involving over one thousand psychiatric patients confirmed both varenicline’s safety and its efficacy in smoking cessation (Anthenelli et al., 2016).

Ideally, behavioral health specialists can become versed in the use of smoking cessation therapies, or even have an expert on-site at the treatment facility. An alternative strategy is referral to California’s state quitline, called “California’s Smokers’ Helpline,” a toll-free service that can be accessed by dialing 1-800-NO-BUTTS (California Smokers’ Helpline, 2017).

The California Smokers’ Helpline is one of the nation’s leading entities and the first quitline created (California Smokers’ Helpline, 2017). It is staffed by seasoned counselors who are able to tailor a treatment plan that fits the circumstances of individual clients. It provides services for non-English speakers, and has a quit rate comparable to that seen in traditional clinical settings. For those on Medi-Cal insurance, the Helpline can provide vouchers for free NRT medications.

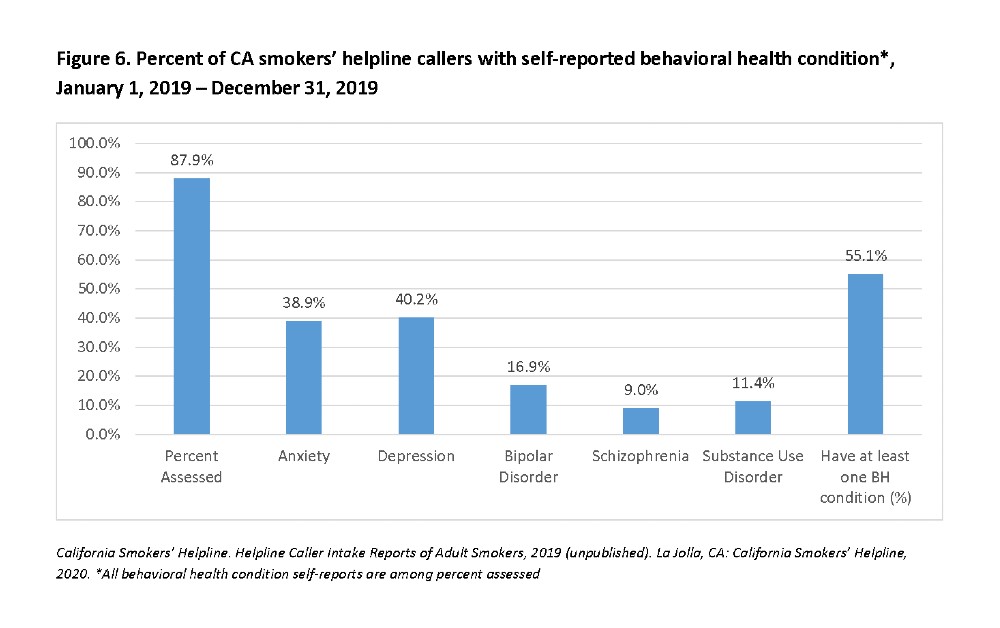

Despite the previously addressed myth that individuals with behavioral health conditions who smoke do not want or do not seek treatment for their tobacco use, call reports from the California Smokers’ Helpline have shown otherwise. According to compiled call reports from 2019, over 55 percent of callers to the Helpline reported having at least on behavioral health condition (California Smokers’ Helpline, 2019; see Figure 6).

Figure 6

As with any medications, care must be taken by the prescribers/providers to ensure that any contraindications from smoking cessation medications do not interfere with other medications clients are on. In fact, an added bonus of stopping smoking is that ingredients in tobacco smoke, not nicotine, increase the catabolism of many commonly prescribed psychiatric medications, often with side effects that are poorly tolerated (Schroeder & Morris, 2010). When patients stop smoking, they can then reduce the dosages of such medications and thereby reduce unwanted side effects.

Tobacco-Free Living in Behavioral Health Treatment Settings

To assist people with behavioral health conditions to live healthy, longer, and more meaningful lives, those who work in health care and social services need to promote behaviors that lead to improved overall wellness. Creating a tobacco-free environment is one of the primary ways that a community health care agency can create a safer and healthier environment for all clients, staff, and visitors.

It is an integral part of promoting and supporting whole-person health for both clients and staff at facilities. Replacing smoke breaks with organized outdoor activities like group walks, gardening, and basketball, or replacing indoor activities with yoga, meditation, and cooking, can help the transition to a tobacco-free life and recovery.

It is also common that the staff who work in behavioral health treatment facilities themselves smoke, especially those who are in recovery from SUDs. It is important to establish guidelines that restrict smoking to off-campus sites, and to offer smoking cessation treatment to these staff members.

In order to transition from a setting that allows smoking on-site, it is important to begin with an inclusive planning process that includes staff who smoke, clients who smoke, administrators, and therapists. In some settings there have been initial concerns about resultant discipline problems or the potential loss of clients. In fact, these have turned out not to be problematic. For more information on tobacco-free treatment centers in California, please see the SAMHSA Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator at https://findtreatment.samhsa.gov/.

Addressing Electronic Cigarettes and Vaping

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) are devices that provide aerosolized nicotine vapor in lieu of smoking combustible tobacco. The devices are in continuous evolution and come in many flavors. They have become very popular with youth, thereby causing alarm among public health experts.

The potential harms and benefits of e-cigarettes have been widely debated and have become a controversial topic in public health and health care. Some experts push for tighter regulation, including banning advertising and flavors, while others wish to preserve the potential of e-cigarettes to as a way for smokers to quit combustible tobacco if they are unable or unwilling to use standard smoking cessation therapies.

Here is what is known so far. E-cigarettes are not FDA-approved cessation devices. While e-cigarettes have the potential to benefit some adults (and harm others), scientists still have a lot to learn about whether e-cigarettes are effective for quitting smoking. Regarding potential harms, most e-cigarettes contain nicotine, which has known health effects, including being highly addicting, potentially harmful to developing fetuses, and interfering with adolescent brain development. There is also concern that e-cigarettes may induce young people to switch to combustible cigarettes (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018), although that does not yet seem to be the case at the population level.

Aside from the nicotine, e-cigarette aerosol can contain other substances that harm the body, including heavy metals and carcinogenic, tobacco-specific nitrosamines. In addition to harms from inhaling the aerosol, e-cigarettes can also cause unintended injuries. Defective e-cigarette batteries have caused fires and explosions, some of which have resulted in serious injuries. In some countries, notably the United Kingdom, e-cigarettes have emerged as a major route for smoking cessation. That is not the case in the United States, however, where their use is very low.

The Mayo Clinic developed a comprehensive questionnaire with intake questions for e-cigarette use (tailored for use in Epic EHR), which can be seen in the sidebar linked here.

Earlier this year an epidemic emerged of severe lung disease involving vaping, with almost three thousand cases involved and almost sixty deaths (CDC, 2019). This condition is called “e-cigarette or vaping associated lung injury” (EVALI). Careful investigation has traced the vast majority of EVALI cases to vaping products found on the black market that contain the cannabis substance THC dissolved in vitamin E acetate oil.

The resultant injury has been attributed to inhaling that oil. There are a small number of cases with no reported THC exposure, and whether they were caused by inhaling e-cigarette vapor is not clear (CDC, 2019). It is likely that e-cigarettes pose fewer health risks than smoking combustible cigarettes, but it is also likely that they are riskier than breathing regular air.

What the CDC Recommends

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advises the following in relation to e-cigarettes (CDC, 2019):

CDC and FDA recommend that people not use THC-containing e-cigarette, or vaping, products, particularly from informal sources like friends, family, or in-person or online dealers.

Vitamin E acetate should not be added to any e-cigarette, or vaping, products. Additionally, people should not add any other substances not intended by the manufacturer to products, including products purchased through retail establishments.

Adults using nicotine-containing e-cigarette, or vaping, products as an alternative to cigarettes should not go back to smoking; they should weigh all available information and consider using FDA-approved smoking cessation medications. If they choose to use e-cigarettes as an alternative to cigarettes, they should completely switch from cigarettes to e-cigarettes and not partake in an extended period of dual use of both products that delays quitting smoking completely. They should contact their health care professional if they need help quitting tobacco products, including e-cigarettes, as well as if they have concerns about EVALI.

The Bottom Line

Regardless of individuals’ behavioral health conditions, the most important thing people can do to improve their health, well-being, and life span is to quit smoking. As health care providers, the most effective ways we can assist those individuals in their journey to live tobacco free are by providing evidence-based cessation services and resources while supporting tobacco-free environments.

For more information on how to address smoking with your clients and how to implement a comprehensive tobacco-free policy, please see the “Tobacco-Free Toolkit for Behavioral Health Agencies” on the Smoking Cessation Leadership Center’s California Behavioral Health & Wellness Initiative (CABHWI) website at cabhwi.ucsf.edu.

References

- American Lung Association (ALA). (2019). What’s in a cigarette? Retrieved from https://www.lung.org/quit-smoking/smoking-facts/whats-in-a-cigarette

- Anthenelli, R. M., Benowitz, N. L., West, R., St Aubin, L., McRae, T., Lawrence, D., . . . Evins, A. E. (2016). Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet, 387 (10037), 2507–20.

- Burke, M. V., Hays, J. T., & Ebbert, J. O. (2016). Varenicline for smoking cessation: A narrative review of efficacy, adverse effects, use in at-risk populations, and adherence. Patient Preference and Adherence, 10(1), 435–41.

- California Smokers’ Helpline. (2017). California smokers’ helpline 1-800-NO-BUTTS. Retrieved from https://www.nobutts.org/

- California Smokers’ Helpline. (2019). Helpline monthly intake reports (January 2019 – December 2019). Retrieved from https://www.nobutts.org/california-monthly-intake-reports

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2019). Outbreak of lung injury associated with e-cigarette use, or vaping, products. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html

- Creamer, M. R., Wang, T. W., Babb, S., Cullen, K. A., Day, H., Willis, G., . . . Neff, L. (2019). Tobacco product use and cessation indicators among adults – United States, 2018. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(45), 1013–9.

- Marynak, K., VanFrank, B., Tetlow, S., Mahoney, M., Phillips, E., Jamal, A., . . . Babb, S. (2018). Tobacco cessation interventions and smoke-free policies in mental health and substance abuse treatment facilities – United States, 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(18), 519–23.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Committee on the Review of the Health Effects of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems; Eaton, D. L., Kwan, L. Y., & Stratton, K. (Eds.). (2018). Public health consequences of e-cigarettes. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- Schroeder, S. A., & Morris, C. D. (2010). Confronting a neglected epidemic: Tobacco cessation for persons with mental illnesses and substance abuse problems. Annual Review of Public Health, 31, 297–314.

- Smoking Cessation Leadership Center (SCLC). (2019). Tobacco-free toolkit for behavioral health agencies. Retrieved from https://smokingcessationleadership.ucsf.edu/sites/smokingcessationleadership.ucsf.edu/files/Downloads/Toolkits/362577_CABHWI_Toolkit_020420_WEB2.pdf

- Sullivan, M. A., & Covey, L. S. (2002). Current perspectives on smoking cessation among substance abusers. Current Psychiatry Reports, 4(5), 388–96.

- Taylor, G., McNeill, A., Girling, A., Farley, A., Lindson-Hawley, N., & Aveyard, P. (2014). Change in mental health after smoking cessation: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 348, g1151.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. (2014). The health consequences of smoking—Fifty years of progress: A report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: Author.

- Vuong, T. D., Zhang, X., & Roeseler, A. (2019). California tobacco facts and figures 2019. Retrieved from https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CCDPHP/DCDIC/CTCB/CDPH%20Document%20Library/ResearchandEvaluation/FactsandFigures/CATobaccoFactsandFigures2019.pdf

About Me

Brian Clark is the senior data and project analyst at the Smoking Cessation Leadership Center. He manages and oversees coordination of SCLC’s various projects while providing analysis of campaign metrics.

Catherine Saucedo is the deputy director of the Smoking Cessation Leadership Center. She provides oversight and executive level management for the Center.

Christine Cheng is the partner relations director at the Smoking Cessation Leadership Center. She is responsible for the provision of outreach to accomplish SCLC’s objectives across its local, state, and national network of partners.

Steven Schroeder, MD, is the director of the Smoking Cessation Leadership Center, which began in 2003. He founded the SCLC after serving as president and CEO of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.