Share

We’ve all played the game of “telephone” one or more times in our life. We laugh hilariously at the contorted version of a spoken sentence whispered from one person to another and are amazed at what the last person in the line reports they have heard. At first, we may believe the “breakdown in communication” occurs because the words are whispered from one person to the next, but if we think about it, there is a much simpler reason that the words become so jumbled – because each person is unique and hears from a different perspective.

Communicating what programs and professionals do on a daily basis when treating substance use disorder or working with people in recovery has become a complex game of telephone. In many instances–practitioners, administrators, billers, and payers seem to be speaking different languages. This is not surprising considering the inherently global nature of substance use disorder. Whether it be the physical impact of stimulant use disorder on the body’s cardiac system, the lack of maturity needed to get and hold a job after adolescent misuse of marijuana, or homelessness caused by years of an untreated alcohol use disorder, programs and professionals are often left searching for ways to describe the “inputs” to successful intervention of the disease.

Equally vexing is language to describe improvements to a person’s health and lifestyle, other than are you not deceased, not using, not incarcerated, and are you currently employed? Fortunately, there has been much development in the “recovery capital” front, leading to better methods to describe outcomes in a more “human” way. We are learning and teaching those in treatment and recovery how to classify recovery capital and how to measure it as well. I believe this will lead to significant advancement in outcomes tracking and great gains in people’s ability to guide their recoveries. But, wouldn’t it be great if we could use recovery capital concepts to also measure “inputs” as well as outcomes?

It turns out, we can. Several organizations, including the National Behavioral Association of Providers (NBHAP) in coordination with CCAPP and R1 learning, have meticulously mapped recovery capital terms and concepts to z-codes for social determinants of health for billing communications purposes. The US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion defines social determinants of health (SDOH) are “the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.” (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. [n.d.])

SDOH encompass five basic domains: economic stability, education access and quality, healthcare access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, and social and community context. These domains can contribute to or decrease a person’s overall health and play a significant role in supporting one’s recovery from both substance use disorder and mental health diagnoses. They also speak to the concepts described with recovery capital however clumsily. They are not an exact match to recovery capital terminology and concepts, in part because they are meant to describe one’s overall health and well-being potential and are not necessarily tied to addiction and recovery, but they do correlate in a “telephone game” like way. So, wouldn’t it be incredibly useful if someone could cut through the “crossed wires” and describe SDOH in recovery capital terminology so that z-codes could be established for them?

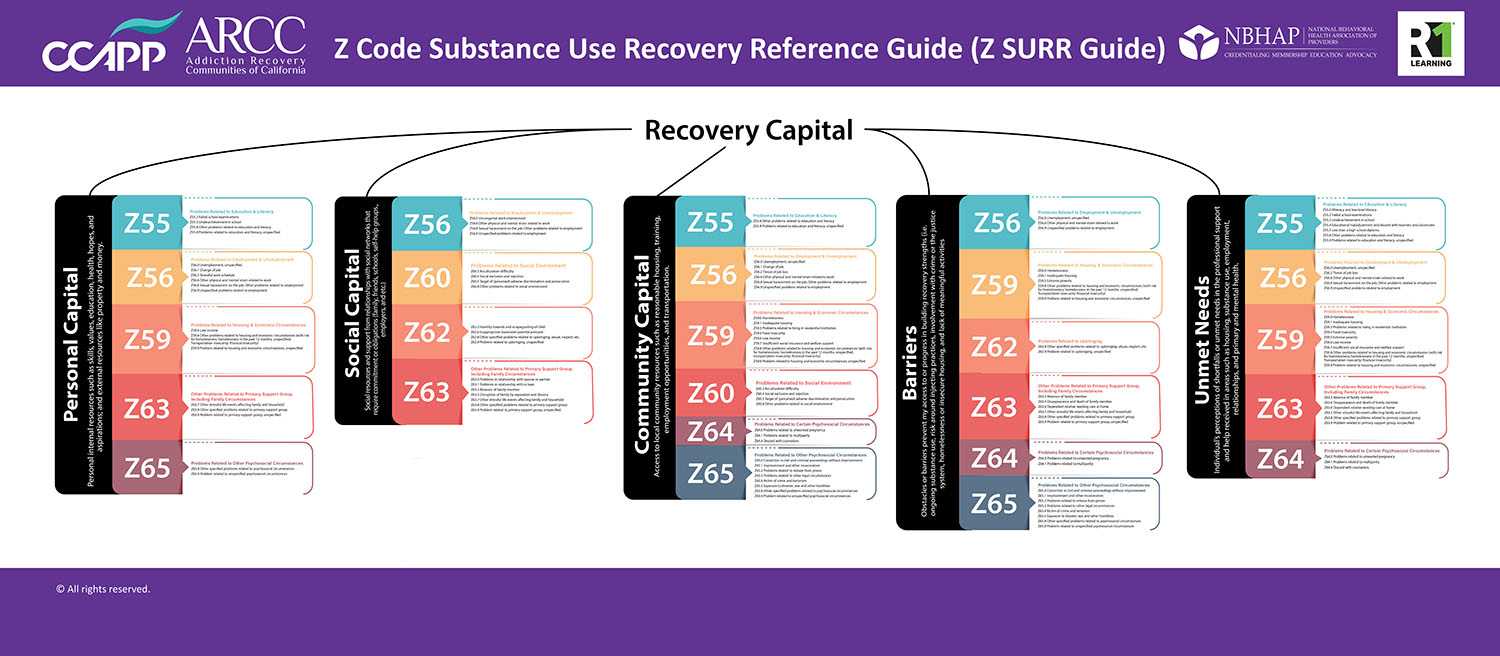

NBHAP and R1 Learning have both developed crosswalks to describe what substance use disorder programs and professionals do to impact SDOH and have categorized them according to recovery capital “buckets” so that practitioners can efficiently communicate to the rest of the world what “inputs” are being employed to improve recovery capital/SDOH in a z-code format. Z-codes for describing social determinants of health are rooted in the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) and offer an opportunity to improve data collection on SDOH, but they also provide an ability to describe substance use disorder treatment and recovery services in a language that all can understand.

Z-codes denote reasons for encounters. So, when a billing office uses this code, it is to be used along with a primary diagnosis code that describes the illness or injury, or as a primary code when an encounter involves a patient without a confirmed diagnosis or another billing code. Grouping these codes to align with recovery capital terminology reduces confusion, guides practitioners in documenting interventions, and creates avenues for valuing work performed in these areas In other words if you cannot adequately describe a service in ways that are generally understood, the potential for receiving reimbursement for them is ultimately reduced. Using a Recovery Capital screening tool such as the REC-CAP, RCS, or RCI might be a better way to screen for SDOH, because it can give more depth then a check box and the information can be used to help increase their Recovery Capital/SDOH factors. The Z Code Substance Use Recovery Reference Guide (Z SURR Guide) is a tool that can be used to crosswalk Z-codes to Recovery capital and vice versa. The RCS as an add layer of screening for barriers and unmet needs that can be helpful assist individuals’ immediate needs.

If we are to think in terms of aligning terminology, it is easy to see that working with a client who is experiencing social rejection and exclusion (stigmatization) neatly fits under the recovery capital category “Social Capital” while also falling under z-code 60 “Problems Related to Social Environment.” Counseling through a loss of job or a change in job due to the impact of substance use disorder would fall under “Personal Capital,” but also falls neatly into z-code 56 “Problems Related to Employment and Unemployment.” But figuring out which category each item belongs to and what z-code to use would be time-consuming and, due to the vague nature of some of the terms, could lead to conflicting results as to which category to choose.

NBHAP and R1 Learning have taken the guesswork out of aligning what we do to SDOHs with Z SURR Guide. We have cut the telephone lines and created a simple graphic that can be used to translate recovery capital to z-coding. As we move forward, we can now all speak the same language.

References

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.). Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health. Office of the Secretary. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from: https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health.

About Me

Pete Nielsen is the President & Chief Executive Officer for the California Consortium of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP), CCAPP Credentialing, CCAPP Education Institute, and the National Behavioral Health Association of Providers (NBHAP). CCAPP is the largest statewide consortium of addiction programs and professionals, and the only one representing all modalities of substance use disorder treatment programs. NBHAP is the leading and unifying voice of addiction-focused treatment programs nationally. Mr. Nielsen has worked in the substance use disorders field for 20 years. In addition to association management, he brings to the table experience as an interventionist, family recovery specialist, counselor, administrator, and educator, with positions including campus director, academic dean, and instructor.

Mr. Nielsen is the secretary of the International Certification and Reciprocity Consortium and the publisher for Counselor magazine. He is a nationally known speaker and writer published in numerous industry-specific magazines. Mr. Nielsen holds a Master of Science in Counseling Psychology and a Bachelor of Science in Business Management.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.