LOADING

Share

Substance and alcohol abuse and dependence is a widespread national and global issue, affecting the health, mental health, and economy of today’s society. According to the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), about 22.2 million people age twelve or older were classified as meeting DSM-IV criteria for substance dependence or substance abuse in the past year in the US (SAMHSA, 2013). Of this number, “17.7 million had alcohol dependence or abuse, and 7.3 million had illicit drug dependence or abuse” according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) (2013). Overall, the rate of alcohol dependence or abuse has declined from 2002–2012 by 7.7 percent, going from 18.1 million people who had alcohol dependence of abuse in 2002 to 17.7 million in 2012 (NIDA, 2014a).

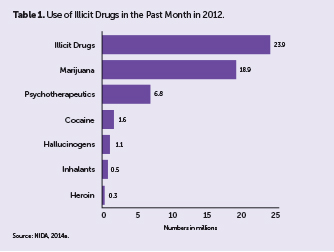

Although statistics show that rates of alcohol abuse and dependence are on the decline, the use of illicit drugs in American has been on the rise over the past ten years. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), “an estimated 23.9 million Americans aged twelve or older—or 9.2 percent of the population—had used an illicit drug or abused a psychotherapeutic medication (such as a pain reliever, stimulant, or tranquilizer) in the past month” in 2012 (2014a). This is an 8.3 percent increase since 2002, and is mainly attributed to the widely increased use of marijuana in recent years and possibly its legalization (see table 1 for numbers of use of illicit drugs types).

Marijuana

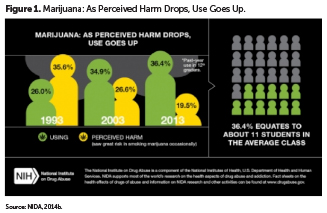

In 2013, the National Institute of Health (NIH) annual Monitoring the Future survey of eighth, tenth, and twelfth graders elicited information on the increased use of marijuana over the past two decades (NIDA, 2014b). The survey found that as the perceived harm of marijuana has steadily decreased, the use of marijuana has steadily increased (NIDA, 2014b). Figure 1 illustrates the statistics on this phenomenon.

Although 60 percent of high school students do not view marijuana use as harmful, the potency of THC in marijuana has increased to a significantly higher level in the past few years, which means that use of today’s marijuana may have greater health consequences than use of marijuana from ten to twenty years ago (NIDA, 2014b). As marijuana has the highest dependence or abuse rate of all drugs after alcohol, and with 4.3 million people meeting clinical criteria of abuse or dependence in 2012, this issue calls for heightened attention and research in the coming years.

Heroin

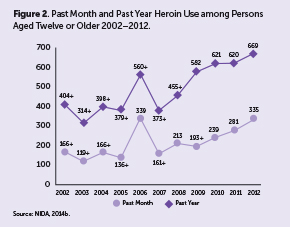

Another persistent issue is the rising rate of heroin use. Numbers have been on the rise since 2007, and according to the 2012 NSDUH, 669,000 people used heroin in the past year (NIDA, 2014c). Additionally, about 156,000 people used heroin in 2012, which is nearly double the number of people in 2006 (NIDA, 2014c). The NIDA report on the issue of heroin highlights the issue in St. Louis as well as Chicago, reporting that the heroin use in these cities has been on the rise not only in urban areas, but also in suburban and rural areas. There have been significant increases in the amount of heroin seized by officials in St. Louis, as well as shockingly high and tragic increases in the numbers of people dying of overdose by heroin (NIDA, 2014c). The changing scope and prevalence of the use of heroin is a particularly concerning and pressing issue in the US and globally, especially in light of the serious health risks associated with use of this highly addictive drug. Figure 1 displays the recent heroin use numbers.

Economic Cost to Society

Substance abuse—including abuse of alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drugs—is highly costly to American society, “exacting over $600 billion annually in costs related to crime, lost work productivity, and health care” (NIDA, 2012). According to NIDA (2012):

- Tobacco costs $96 billion in health care and $193 billion overall

- Alcohol costs $30 billion in health care and $235 billion overall

- Illicit drugs cost $11 billion in health care and $193 billion overall

These high costs to the country illustrate the need for increased efforts to invest in effective prevention and intervention programs across the US. Despite the high costs to society, a large treatment gap continues to persist across the board as the number of people needing treatment for substance abuse or dependence is significantly higher than those receiving treatment (NIDA, 2014a).

Treatment Need vs. Treatment Received

The availability and utilization of substance abuse treatment is highly disparate from the prevalence of the need for such services. According to NSDUH, 23.5 million people age twelve and older needed substance abuse treatment in 2009 (NIDA, 2011). However, according to NIDA only 2.6 million (11.2 percent) actually received treatment at a specialized addiction treatment facility (2011). In 2012, eight million people aged twelve and older needed treatment for illicit drug use, while only 1.5 million or 19.1 percent of those people received specialized treatment (SAMSHA, 2013). For alcohol abuse treatment in 2012, 18.3 million people aged twelve and older needed treatment, while only 1.5 million or 8.2 percent received specialized treatment for the issue (SAMSHA, 2013). There is clearly an issue regarding the disparity between the need for and receipt of treatment for problems with substance abuse and dependence.

From 2006–2012, NSDUH collected information on the most common reasons that those needing treatment for substance abuse did not receive appropriate specialized services. It states:

Based on 2009–2012 combined data, the six most often reported reasons for not receiving illicit drug or alcohol use treatment among persons aged twelve or older who needed and perceived a need for treatment but did not receive treatment at a specialty facility were (a) not ready to stop using (40.4 percent); (b) no health coverage and could not afford cost (34.0 percent); (c) possible negative effect on job (12.0 percent); (d) concern that receiving treatment might cause neighbors/community to have a negative opinion (11.6 percent); (e) not knowing where to go for treatment (9.1 percent); and (f) had health coverage but did not cover treatment or did not cover cost (7.9 percent) (SAMSHA, 2013).

This data presents important information regarding the barriers to receiving treatment. After not being ready to stop using, the most common barrier to receiving treatment was lack of health insurance and inability to afford treatment. These issues point to a huge problem in the field of substance abuse: the continued stigma against those struggling with substance abuse or dependence. Due to the stigma against and blame on people with substance abuse issues or viewing the issue as sinful and due to a lack of willpower or morality, there is a clear lack of funding for treatment facilities and a failure of health insurance to cover the costs. Additionally, 9.1 percent of those needing treatment did not know where to go for treatment. Together, the persisting stigma and lack of knowledge of treatment facilities highlight the continued need for outreach, spreading awareness, and distributing correct information to reduce stigma and advocate for more funding and more affordable specialized treatment facilities.

Common Models and Methods for Treatment

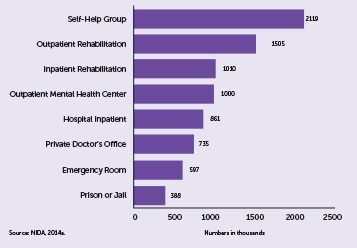

There are various settings for substance abuse and dependence treatment. The most common settings reported in the 2012 NSDUH are as follows, starting with the most common (SAMHSA, 2013):

- Self-help group

- Outpatient rehabilitation

- Inpatient rehabilitation

- Outpatient mental health center

- Hospital inpatient

- Private doctor’s office

- Emergency room

- Prison or jail

Table 2 provides the numbers of people receiving treatment at each location.

There are several traditional approaches upon which substance abuse treatment is commonly based, including the medical model, the social model, and the behavioral model (US Department of Health and Human Services, 1999).

The Medical Model

The medical model views addiction as a biological disease and emphasizes the need for lifelong abstinence through long-term recovery and support programs (US Department of Health and Human Services, 1999). The medical or disease model defines addiction as “a primary, chronic, and progressive disease, probably cause by a genetic predisposition” (Fisher & Harrison, pp. 38, 2013). This approach can be compared to the way that other chronic diseases, such as diabetes, are viewed and treated.

The Social Model

The social model for treatment focuses on long-term abstinence and encourages peer support or self-help groups to maintain sobriety (US Department of Health and Human Services, 1999). Social treatment models may be based in sociocultural or biopsychosocial models of addiction, which view addiction in light of multiple interacting variables, including cultural, religious, ethnic, and environmental factors (Fisher & Harrison, 2013).

The Behavioral Model

The behavioral treatment model focuses more on diagnosis and treatment of other problems which can interfere with the recovery process (US Department of Health and Human Services, 1999). In light of behavioral theory, behavioral treatment views addiction as a learned and reinforced behavior and recognizes the need for relearning and reinforcing new behaviors that are necessary for leading a sober life (Fisher & Harrison, 2013). This implies that behavioral treatment is based in the psychological model of addiction, which views addiction as a symptom of other underlying psychological disorders.

Current Treatment Practices

A variety of practices are currently being used in the field of addiction treatment. Despite the fact that there are numerous evidence-based treatment practices in existence, treatment facilities do not necessarily implement all of these practices. Different approaches to treatment exist based on the model of addiction to which an agency adheres (Fisher & Harrison, 2013).

Two common treatment practices for alcohol and substance use disorders involve the use of pharmacotherapy: detoxification and aversion therapy (Fisher & Harrison, 2013; Fuller & Hiller-Sturmhofel, 1999). Detoxification, or the process of removing toxic substances from a person’s system, is often employed with clients who are addicted to Central Nervous System (CNS) depressants, which have harmful withdrawal effects. The “withdrawal syndrome from CNS depressants can be medically dangerous” and symptoms may include “anxiety, irritability, loss of appetite, tremors, insomnia, and seizures” (Fisher & Harrison, 2013, pp. 21). Clients undergoing withdrawal from CNS depressants may be in serious danger due to withdrawal symptoms, and withdrawal may even be lethal. Therefore, in a clinical setting, minor tranquilizers can be used to reduce the severity of the withdrawal symptoms. Detoxification can provide a relief of withdrawal symptoms to clients and prevent relapse.

Another use of pharmacotherapy is in aversion therapy, a behavioral technique commonly used in the treatment of problematic AOD use. Aversion therapy “seeks to develop in the client, via classical Pavlovian conditioning, a conditioned negative response to the sight, smell, taste, and even thought of alcohol” (Fisher & Harrison, 2013, pp. 140). This response is typically achieved through the introduction of negative stimuli, which are learned to be associated with the user’s drug of choice. This may be induced using pharmaceuticals that cause nausea and sickness when the drug is used, such as the drug Antabuse, which is used as aversion therapy for alcohol. In the past, shock therapy and various images have also been used as aversion therapy.

Nonmedication treatment practices include therapeutic models such as the Minnesota model, contingency management programs, motivational interviewing, brief outcome interventions, and Twelve Step facilitation. The Minnesota Model is one of the most widely used treatment approaches for severe substance abuse across the US (Winters, Stinchfield, Opland, Weller, & Latimer, 2000), and it is comprised of four components:

- The first component is the belief that clients can change their “attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors” (Fisher & Harrison, 2013, pp. 139).

- Secondly, the Minnesota model aligns with the medical model of addiction, which views addiction as a disease rather than a lack of morality or a choice.

- The third component of the Minnesota model emphasizes the importance of remaining abstinent from mood-altering chemicals.

- The fourth component of the Minnesota model is the integration of Twelve Step programs in treatment, such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous (NA).

Other common current treatment practices include programs such as AA and NA, which have a heavy emphasis on peer support and spirituality (CSAT, 1997; Fisher & Harrison, 2013; Fuller & Hiller-Sturmhofel, 1999). Treatment practices that emphasize behavioral change include contingency management plans and cognitive behavioral therapy. Lastly, brief interventions are used in primary care settings for people who may be presenting drinking problems or are at a higher risk of developing substance abuse or dependence (Fuller & Hiller-Sturmhofel, 1999). Brief interventions differ from therapeutic interventions in that brief interventions are more focused on motivating a client to make a particular change or perform a particular action, such as entering treatment or changing a behavior.

Effectiveness of Current Practices

Pharmacotherapy practices are commonly used to treat AOD disorders. Medications frequently prescribed to treat AOD disorders include methadone, buprenorphine, Antabuse, naltrexone, and acamprosate. According to Fuller and Hiller-Sturmhofel, “Therapists primarily use two types of medications in alcoholism treatment: (1) aversive medications, which deter the patient from drinking, and (2) anticraving medications, which reduce the patient’s desire to drink” (1999, pp. 75). Antabuse is a common drug used to treat alcohol use disorders. Researchers found that poor compliance taking Antabuse nullified its effectiveness and recommend client supervision from therapists or family members to be most effective for clients on this drug (Fuller & Hiller-Sturmhofel, 1999). Fuller and Hiller-Sturmhofel also studied the effects of anticraving medications such as naltrexone and acamprosate (1999). Research revealed naltrexone has been effective at resulting in a reduction in relapse rates, whereas acamprosate treatment has been shown to double the abstinence rate among recovering alcoholics (Fuller & Hiller-Sturmhofel, 1999). Thus, certain pharmacotherapy approaches can be effective treatment methods for substance abuse and dependence.

When analyzing the effectiveness of therapeutic approaches, Fuller and Hiller-Sturmhofel (1999) conducted a multisite study designed to identify patient characteristics that would predict the most beneficial treatment approaches for alcohol abuse. Two groups of participants made up the sample: the aftercare sample and the outpatient sample. Participants were randomly assigned to receive cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), motivational enhancement therapy (MET) or Twelve Step facilitation therapy (TSF). Interventions were administered over twelve weeks in individual outpatient sessions. In the aftercare sample, “no differences were found in the efficacy of CBT, MET, and TSF during the year following treatment” (Fuller & Hiller-Sturmhofel, 1999, pp. 74). However, differences that did exist favored TSF as the most effective practice to maintain client abstinence from alcohol use. Additionally, brief interventions implemented by a primary care physician have been shown to be “effective in reducing drinking among people who have alcohol-related problems or who are at risk for such problems” (Fuller & Hiller-Sturmhofel, 1999). Overall, CBT, MET, TSF, and brief interventions are effective and valuable treatment options for substance abuse and dependence and can be utilized in a variety of settings, including inpatient, outpatient, and doctor’s office settings.

Treatment Demographics

As previously mentioned, about twenty-three million persons over the age of twelve needed some level of treatment for an illicit drug or alcohol abuse problem (NIDA, 2011). Of these, the NSDUH 2012 study discovered only 2.6 million (11.2 percent) of those who needed treatment received it at a specialty facility. In 2008, there was a reported 1.8 million admissions to rehabilitation facilities. Alcohol use accounted for the majority of treatment admissions at 41.4 percent. Additionally, heroin and other opiates accounted for the largest percentage of admissions (20.0 percent) for drug use, followed by marijuana (17.0 percent) (NIDA, 2011).

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (2011), 60 percent of admissions were white, 21 percent African American, 13.7 percent Hispanic, 2.3 percent American Indian or Alaska Native, 1.0 percent Asian/Pacific Islander, and 2.3 percent identified as “other.” Data shows that younger adults are at a greater risk for developing a substance use disorder. In fact, the age range with the highest proportion of treatment admissions was the twenty-five to twenty-nine age group at 14.8 percent, followed by those aged twenty to twenty-four at 14.4 percent and those aged forty to forty-four at 12.6 percent (NIDA, 2011). In stark contrast, persons sixty-five and older accounted for less than 1 percent of admissions. Moreover, persons under the age of eighteen accounted for approximately 7 percent of all clients in substance abuse treatment facilities (NIDA, 2011).

The 2012 National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS) surveyed 14,311 substance abuse treatment facilities nationwide. The survey revealed that both the total number of substance abuse facilities and the number of clients in treatment increased by 5 percent between 2008 and 2012. In terms of specific interventions, the number of clients receiving methadone treatment increased 3 percent during this time frame. In addition, clients receiving buprenorphine ranged from 1 to 3 percent in the period of 2008 to 2012 (SAMHSA, 2012).

The N-SSATS (2012) also polled treatment facilities to gather information about specific client types most frequently served and found that the most common types of clients in treatment facilities are as follows:

- Clients with co-occurring disorders (5,288)

- Adult women (4,470)

- DUI/DWI offenders (4,107)

- Adolescents (4,008)

- Adult men (3,550)

Other client types include criminal justice clients, persons who have experienced trauma, pregnant or postpartum women, persons with HIV/AIDS, veterans, seniors, LGBTQ individuals, active duty military, and members of military families (SAMHSA, 2012). The survey also found that the majority of clients, 11,764, fell within the any program or group category, which is an open group (SAMHSA, 2012).

Cultural Considerations in Treatment

It is important to consider how factors of diversity impact clients’ treatment and recovery processes. Treatment for diverse groups such as racial minorities, the elderly, adolescents, persons with disabilities, pregnant women and mothers, the criminal justice population, and persons with co-occurring disorders should be carefully adjusted and adapted to ensure that the population’s particular needs are met and that they receive culturally sensitive, high quality services. Therefore, when working with ethnically diverse populations, it may be important to be mindful of the diversity of the treatment staff in an effort to increase client comfort. When working with individuals from differing backgrounds, treatment staff should be aware that “the attitude of an ethnic group toward AOD problems may present a barrier for the individual seeking treatment” and find ways to approach that issue in a culturally sensitive manner (Fisher & Harrison, 2013, pp. 153).

For example, in the African American community, some may view alcoholism as immoral. In a study conducted by Acevedo et al. (2012), African American clients were 14 percent less likely to initiate treatment for AOD use than white clients. It is imperative that treatment facilities address potential barriers to treatment and assess whether or not they administer culturally sensitive and appropriate care. In an effort to ensure that individuals from varying cultures receive adequate care, “substance abuse screening in medical settings should continue to be promoted for all patients, and this may play an especially strong role in increasing access to treatment in minority [populations] . . .” (Acevedo et al, 2012, pp. 14). This data again shows the importance of the role of primary care practitioners in the continuum of AOD treatment.

Providing services to the elderly population brings about unique challenges. Specifically, society tends to hold more lenient attitudes toward elders who use AOD, which places this population at greater risk for developing a substance use disorder (Fisher & Harrison, 2013). Elderly individuals have a slower metabolism, which is important to consider because it impacts tolerance. Another factor to consider is that members of this population are beginning a new phase in life with retirement and often the loss of loved ones. Elderly individuals may be dealing with issues of bereavement from the loss of a spouse or friend, which could lead to the use of AOD as a coping mechanism (Fisher & Harrison, 2013).

Persons with disabilities represent another vulnerable population in the AOD use field. Treatment programs may require clients to complete extensive reading and writing exercises, which may be difficult for persons with learning disabilities (Fisher & Harrison, 2013). For persons with physical disabilities, AOD use may serve as a coping mechanism for loss of autonomy or independence. Furthermore, Fisher and Harrison state that treatment programs may not accommodate the hearing impaired, seeing impaired or low literacy level clients (2013).

Pregnancy is a unique challenge to women in treatment settings. However, “family-centered approaches such as family drug courts and residential treatment for pregnant and parenting women have shown promising results” (Stevens, Andrade, & Ruiz, 2009, pp. 354). The prevalence of extensive trauma history is particularly high for women with substance abuse issues. Many women may present with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms in treatment settings as a result. Research has shown women-only treatment centers are not more effective than mixed-group treatment centers, but should be taken into consideration when addressing sensitive topics in therapy such as unresolved trauma, pregnancy, and parenting (Fisher & Harrison, 2013; Stevens et al., 2009).

The criminal justice population is often referred to drug court and DUI school as a means of treatment for problematic AOD use. These methods of treatment are often short-term solutions and lack comprehensive care. Additional “comprehensive service, community links and aftercare services” are needed for this population (Fisher & Harrison, 2013, pp. 158). Research has shown that the criminal justice system can provide incentive for inmates to participate in treatment because doing otherwise may mean a return to prison or jail (Acevedo et al., 2012). However, coercion into treatment is problematic because it eliminates clients’ autonomy and right to self-determination—clients may also lack the internal motivation needed for successful treatment.

Lastly, treatment of clients with co-occurring disorders is unique and requires special attention of its own. Other mental disorders are often viewed as secondary to the substance use disorder. As a result, clients with severe psychiatric problems can be viewed as inappropriate for AOD treatment programs (Fisher & Harrison, 2013). To further complicate the treatment process, the effects of AOD use can mimic schizophrenia and other mental disorders, making it difficult for clinicians and doctors to discern the etiology of clients’ behavior (Fisher & Harrison, 2013). Detoxification may be necessary to provide an accurate diagnosis. A team approach comprised of mental health and addiction counselors would effectively address clients’ needs with co-occurring disorders.

Conclusion

It is clear that substance abuse disorders continue to be a prevalent and pressing problem across the US. Although the issue is widespread and cuts across racial, socioeconomic, and geographical barriers, there continues to be a glaring gap in the numbers of people who need AOD treatment and the number of those who receive it. Fortunately, research continues to point to many effective treatment practices for substance abuse and dependence. Pharmacotherapy, behavioral approaches, cognitive behavioral therapy, motivation enhancement therapy, Twelve Step facilitation, and brief interventions are all effective in treating people struggling with substance abuse and dependence. It is critical to ensure that the practitioner takes care to meet the particular cultural differences of the individual client and approaches treatment from a culturally sensitive perspective, no matter which evidence-based practice is utilized. Lastly, as the substance abuse field continues to grow and change, it is essential for substance abuse practitioners to stay current with best practices in the research and remain adaptable and flexible to trends in the field.

Acknowledgements: This work was supported by the Community-Academic Partnership on Addiction (CAPA).

References

Acevedo, A., Garnick, D. W., Lee, M. T., Horgan, C. M., Ritter, G., Panas, L., . . . Reynolds, M. (2012). Racial and ethnic differences in substance abuse treatment initiation and engagement. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 11(1), 1–21.

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT). (1997). A guide to substance abuse services for primary care clinicians. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64827/

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT). (1999). Brief interventions and brief therapies for substance abuse. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64947/

Fisher, G. L., & Harrison, T. C. (2013). Substance abuse: Information for school counselors, social workers, therapists, and counselors (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Fuller, R. K., & Hiller-Sturmhofel, S. (1999). Alcoholism treatment in the United States: An overview. Alcohol Research & Health, 23(2), 69–77.

National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). (2011). DrugFacts: Treatment statistics. Retrieved from http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/treatment-statistics

National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). (2012). Trends and statistics. Retrieved from http://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics#costs

National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). (2014a). DrugFacts: Nationwide trends. Retrieved from http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/nationwide-trends

National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). (2014b). Monitoring the future 2013 results. Retrieved from http://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/infographics/monitoring-future-2013-survey-results

National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). (2014c). Heroin. Retrieved from http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/heroin/scope-heroin-use-in-united-states

Stevens, S. J., Andrade, R. A. C., & Ruiz, B. S. (2009). Women and substance abuse: Gender, age, and cultural considerations. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 8, 341–58.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2012). National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N—SSATS): 2012. Data on substance abuse treatment facilities. Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/DASIS/NSSATS2012_Web.pdf

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2013). Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of national findings. Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2012SummNatFindDetTables/NationalFindings/NSDUHresults2012.htm

US Department of Health and Human Services. (1999). Blending perspectives and building common ground: Report to Congress on substance abuse and child protection. Retrieved from http://aspe.hhs.gov/hsp/subabuse99/subabuse.htm

Winters, K. C., Stinchfield, R. D., Opland, E., Weller, C., & Latimer, W. W. (2000). The effectiveness of the Minnesota Model approach in the treatment of adolescent drug abusers. Addiction, 95(4), 601–12.

Previous Article

Sculpturing Frozen Moments

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.