LOADING

Share

Per recent legislation signed into law and subsequent requirement from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), all US health care settings should have successfully transitioned to ICD-10 diagnostic codes by October 1 of last year in order to maintain HIPAA compliance on claim submissions (CMS, 2014). Although the clinical use of the DSM classification system remains commonplace in the US, with the federal mandate that providers assign ICD-10 billing codes, empirical evidence is necessary to determine if the DSM-5 substance use disorder (SUD) diagnoses do in fact map onto their corresponding ICD-10 billing codes. Evaluating the compatibility of diagnostic classification systems is an important area of research in that the implications derived from such work directly impact all phases of SUD treatment from the initial intake assessment to billing and reimbursement for treatment services. The DSM-5 contains all necessary information to assign HIPAA-compliant ICD-10 codes to the SUD diagnoses included in the DSM-5. ICD-10 codes are embedded in parentheses within the diagnostic criteria box for each SUD. According to DSM-5 guidelines, individuals with either a moderate or severe SUD diagnosis are to be assigned the same dependence code for ICD-10 billing purposes, whereas those with a mild diagnosis are to receive a harmful use code.

As a result of conceptual and empirical problems noted for the DSM-IV (APA, 1994) SUD criteria (e.g., Hasin et al., 2013), as well as the issue of diagnostic orphans—that is, those individuals who meet one or more of the diagnostic criteria for DSM-IV substance dependence, yet fail to report indications of abuse, often going undiagnosed when applying traditional classification standards—the fifth edition of the DSM (APA, 2013) featured several changes to the classification of SUDs. Specific changes included, most notably, a shift from the traditional categorical approach to a dimensional approach, as well as the removal of the recurrent legal problems criterion (DSM-IV abuse criterion three), addition of a criterion representing craving, and collapsing the DSM-IV abuse and dependence criteria into a single unified SUD category of graded clinical severity. According to the DSM-5, a minimum of two criteria are now required to assign a SUD diagnosis, whereas only one was required for the DSM-IV. SUD diagnoses also now include three severity specifiers based on the number of positive symptoms from a total of eleven possible criteria: mild (two to three criteria), moderate (four to five criteria), and severe (six or more criteria).

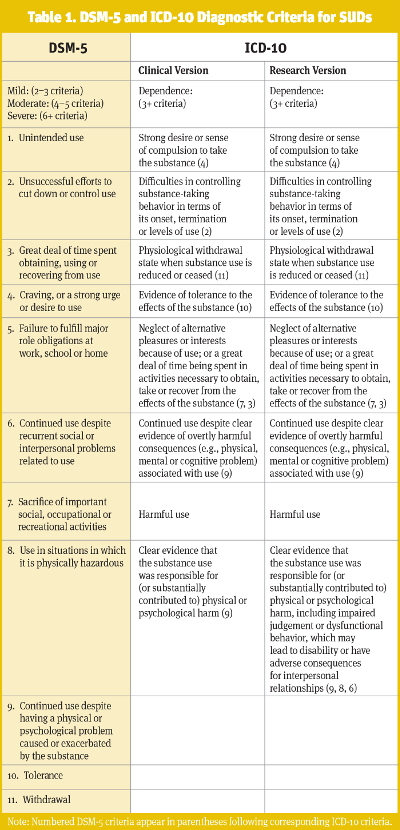

In addition to the DSM-5, providers may use the World Health Organization’s (WHO; 1992a) ICD-10 to formulate diagnostic determinations. Although the DSM-5 is most commonly used in clinical practice—especially in the US—the ICD-10 is to be used for billing and reimbursement. While both the DSM-5 and ICD-10 may be used for diagnostic purposes, there is wide variation in the specific criteria and number of symptoms used to arrive at a SUD diagnosis. That is, the ICD-10 utilizes a categorical approach to the classification of SUDs and includes two primary diagnoses: harmful use and dependence. Harmful use is broadly defined as a pattern of psychoactive substance use that causes damage to the mental (e.g., depressive episodes secondary to heavy consumption of a particular substance) or physical (e.g., hepatitis C) health of the substance user. Dependence, on the other hand, requires the presence of three or more of six specific individual criteria, occurring within a twelve-month period. There are also two versions of the ICD-10 currently available: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines, the clinical version (ICD-10-C; WHO, 1992b), and Diagnostic Criteria for Research, the research version (ICD-10-R; WHO, 1993). However, the clinical version is the one most commonly used in practice on claim submissions. The research version is more inclusive than the clinical version in that the definition of harmful use per the research version is expanded to include impaired judgment and/or dysfunctional behavior in addition to mental and physical harm only, as it is defined in the clinical version. Given that the clinical version is more restrictive and presumably used more often by providers in routine practice, providers may elect to assign the “other” specified code (F1x.8) in instances in which individuals may not qualify for a dependence or harmful use diagnosis under the more restrictive clinical definition, but still present with alcohol-related impairment. A detailed comparison of diagnostic criteria for each of the three approaches—the DSM-5, ICD-10-C, and ICD-10-R—is presented in Table 1.

Agreement between the DSM-5 and ICD-10

Current published work in this area has largely focused on evaluating the compatibility between the DSM-5 and ICD-10 for alcohol, marijuana, and cocaine use disorders (Hoffmann & Kopak, 2015; Kopak, Hoffmann, & Proctor, 2015; Proctor et al., 2016). In terms of the observed past twelve-month prevalence rates of SUDs, our research has shown that DSM-5 criteria performed similarly to ICD-10 criteria in that a comparable number of individuals with any DSM-5 diagnosis also met ICD-10 criteria for a harmful use or dependence diagnosis. Additionally, virtually all of those with no diagnosis per the DSM-5 continued to have no diagnosis when ICD-10 criteria were applied, and nearly all of those with a DSM-5 severe SUD diagnosis received an ICD-10 substance dependent diagnosis. However, concordance between systems for the other diagnoses was considerably lower. Much of the variation between classifications was accounted for by those with a DSM-5 mild or moderate SUD diagnosis. Specifically, roughly one-third of DSM-5 mild cases did not meet criteria for an ICD-10 diagnosis. Furthermore, approximately half of those with a DSM-5 moderate SUD did not meet ICD-10 criteria for substance dependence, and instead most received a harmful use diagnosis.

It is important to mention that the three aforementioned research studies investigating the compatibility between the DSM-5 and ICD-10 criteria for SUDs focused on alcohol, marijuana, and cocaine only. As such, although we have found that these three studies produced similar results, we do not have data on opioids or other simulants (e.g., amphetamines) to verify that the relationships also hold true for other substances. Replication work with samples in clinical treatment settings for the other substances is a logical next step for future research efforts.

Implications for Clinical Practice

Together, the preliminary findings from these three studies translate to potentially reduced access to treatment services for a fairly large number of individuals based on the classification system used. Also of interest, results revealed that for the DSM-5 moderate SUD diagnosis, its corresponding ICD-10 dependence billing code may not accurately represent the symptom constellation present for many DSM-5 moderate cases. From a reimbursement perspective, although DSM-5 moderate and severe SUDs are both to receive an ICD-10 dependence billing code, the provision of more intensive services and expectations of abstinence may not be required for all individuals with a moderate SUD. Considering the limited amount of longitudinal studies in this area to date, the question regarding the potential impact of the observed differences cannot be addressed, and warrants further research. Given the differential outcome expectations for individuals with a DSM-IV substance dependence diagnosis compared to individuals with a DSM-IV substance abuse diagnosis (e.g., Dawson, Ting-Kai, Chou, & Grant, 2009; de Bruijn, van den Brink, de Graaf, & Vollebergh, 2006; Schuckit et al., 2001), the variation in the observed findings may be noteworthy. Therefore, findings suggest that for some individuals, differentiating between DSM-5 moderate and severe SUDs in terms of their billing codes may be indicated. Additional work is clearly warranted in order to answer the question of whether the three SUD designations represent distinct conditions with different clinical courses and treatment outcomes.

Despite a generally high level of agreement between the DSM-5 and ICD-10 diagnostic classification systems in terms of SUD prevalence and those individuals on the higher end of the severity continuum (i.e., DSM-5 severe and ICD-10 dependence), there are likely some very important individual differences between these groups in terms of their clinical presentation. That is, while the ICD-10 is concerned with the pattern of specific symptoms, the DSM-5 relies on a symptom count to assign a diagnosis. For example, clinicians assign a severe SUD diagnosis per the DSM-5 based on the presence of six or more of the eleven criteria, regardless of what specific symptoms are endorsed. The DSM-5’s symptom count strategy results in a minimum of 462 unique combinations of symptoms for a severe SUD diagnosis. In fact, one may indeed question if SUDs really constitute one syndrome with so many combinations. In light of the wide variation in the specific criteria used to arrive at a diagnosis between systems, additional research is necessary to identify relevant prognostic factors and determine the clinical course for the three SUD designations of the DSM-5: mild, moderate, and severe. An important question that has yet to be addressed in the research literature is whether the severe SUD designation of the DSM-5 will result in effectively identifying those with a more pronounced clinical profile and identify those with a more chronic course relative to the other DSM-5 diagnostic categories; particularly the moderate designation.

The Big Five Criteria

Another topic of interest is whether there is a natural hierarchy among DSM-5 SUD criteria. Interestingly, preliminary studies have identified five individual criteria that, when positive, tend to be found primarily among those with a DSM-5 severe diagnosis (Kopak, Metze, & Hoffmann, 2014; Kopak, Proctor, & Hoffmann, 2012; Proctor, Kopak, & Hoffmann, 2012, 2014). These five criteria—unsuccessful efforts to cut down; craving/compulsion to use; failure to fulfill major role obligations; sacrifice of important social, occupational or recreational activities; and withdrawal—first described by Dr. Norman Hoffmann, are referred to as the “Big Five.” These five criteria appear to operationalize the concept of “loss of control” over substance use (Belin, Belin-Rauscent, Murray, & Everitt, 2013), which posits that once use is initiated by an individual, he or she experiences difficulty moderating use and negative substance-related consequences ensue. This concept has been a cardinal indicator used to distinguish those who require abstinence to achieve remission from those who may be able to successfully moderate their substance use and still achieve remission. Previous research studies investigating the process of remission (i.e., recovery) from SUDs support the idea that remission can be achieved with both abstinence- and moderation-based approaches based on the severity of SUD (Rosenberg, 1993; Stea, Yakovenko, & Hodgins, 2015; van Amsterdam & van den Brink, 2013). This raises two important questions related to the DSM-5 criteria in terms of their potential clinical and economic impact:

- Clinically, do the moderate cases with indications of “loss of control” (i.e., more positive Big Five criteria) have different outcomes compared to moderate cases not positive on any Big Five criteria?

- Economically, should there be a distinction in expected reimbursement for the two moderate SUD groups (i.e., those positive on more Big Five criteria versus those not positive on any Big Five criteria)?

If the answer to the first question indicates that all moderate cases, regardless of their patterns of Big Five criteria, experience outcomes similar to severe cases, then the second question would be irrelevant. Longitudinal work exploring the relationships of the Big Five criteria either individually or collectively with the probability of requiring abstinence for achieving remission is necessary.

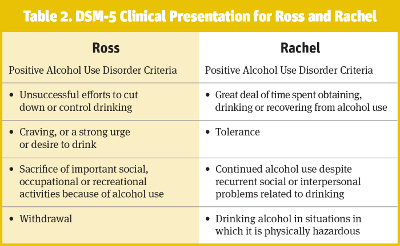

The concept of the Big Five criteria and potential shortcomings of the current DSM-5 dimensionally-based diagnostic system can be further illustrated using two clinical vignettes for the hypothetical cases of “Ross” and “Rachel” (see Table 2). For the purposes of this example, it is assumed both cases are matched on all relevant demographic characteristics known to impact substance use, such as age, race, education level, and socioeconomic status. Similarly, although the two cases differ in sex, it will be assumed that all other biological variables are held constant. Ross and Rachel both present with alcohol-related impairment and are seeking treatment for their problematic alcohol use. As can be seen in Table 2, the results derived from a standard intake assessment evaluation reveal that both cases would receive the same DSM-5 moderate alcohol use disorder diagnosis based on the number of reported symptoms. Although Ross and Rachel do not differ with respect to their assigned DSM-5 alcohol use disorder diagnosis, there are clearly several important distinguishing characteristics between these two cases. Specifically, Ross endorsed numerous indications of a loss of control over alcohol use consistent with the Big Five, while Rachel reported none. Despite these apparent differences in clinical presentation, both would be assigned a DSM-5 moderate alcohol use disorder diagnosis and subsequently receive an ICD-10 alcohol dependence billing code. When we examine the specific symptom endorsement for each case, we see that although Ross meets criteria for alcohol dependence, Rachel unequivocally does not. Rather, Rachel’s symptoms are more consistent with the ICD-10 “other” alcohol use disorder diagnostic category, or at best, a harmful use diagnosis depending on the version of the ICD-10 used. Following DSM-5 guidelines, therefore, would result in misdiagnosing Rachel as alcohol dependent for billing purposes given all DSM-5 moderate cases are to receive an ICD-10 dependence code. From a reimbursement perspective, the level of care and treatment expectations would be the same for both Ross and Rachel even though they likely require different levels of care and could potentially benefit from disparate treatment approaches.

Summary and Recommendations

US health care providers are required to assign ICD-10 billing codes on all claim submissions. According to DSM-5 guidelines, all DSM-5 moderate SUD cases are to be assigned an ICD-10 dependence billing code. However, the findings from our preliminary research indicate that a fairly large number of DSM-5 moderate SUD cases actually do not meet criteria for ICD-10 dependence. This suggests that assigning an ICD-10 dependence billing code to all individuals diagnosed with a DSM-5 moderate SUD may not be entirely accurate and could potentially have some very important clinical and economic implications for practice. Clinical issues include whether the patterns of positive DSM-5 criteria may be as important, in some cases, as the number of positive criteria. This is related to the question of whether the dimensionally-based diagnoses of the DSM-5 actually identify distinct conditions—as implied by the ICD-10—or simply variations in severity. This also raises the economic issue of appropriate reimbursement given the expectation is that dependent individuals have not only different treatment needs, but require more extensive and consequently expensive services.

One viable option for addiction treatment providers would be to move beyond simply documenting the presence or absence of a given DSM-5 diagnosis, and instead, monitor and record the frequency of each of the eleven individual DSM-5 diagnostic criteria. Such an effort would require assessing for the occurrence of each of the eleven criteria for the various substance classes—alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, heroin, and others—for a given individual, and entering those data directly into the patient’s chart or electronic medical record. Rather than assigning a DSM-5 diagnosis only, providers may be better served by documenting the specific criteria for which the patient is positive. Providers who regularly collect and document such information could then correlate those findings with treatment response and completion. If the treatment program has an established outcomes monitoring system in place in which patients are contacted at regular pre-determined intervals post-discharge (e.g., three, six, nine, and twelve months), it would also be possible to tie the Big Five findings to whether or not remission is achieved as well as additional relevant outcomes (e.g., health care utilization, employment functioning) that may be of great value to stakeholders. Such efforts would likely require minimal modifications to existing intake assessment practices, and would allow a treatment program to more precisely identify patients more or less likely to be successful and experience favorable outcomes. The patterns of positive diagnostic criteria could also potentially inform patients’ treatment plans and the selection of appropriate long-term treatment goals.

References

American Psychiatric Association (APA). (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychiatric Association (APA). (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Belin, D., Belin-Rauscent, A., Murray, J. E., & Everitt, B. J. (2013). Addiction: Failure of control over maladaptive incentive habits. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 23(4), 564–72.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). (2014). Deadline for ICD-10 allows health care industry ample time to prepare for change. Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/mediareleasedatabase/press-releases/2014-press-releases-items/2014-07-31.html

Dawson, D. A., Ting-Kai, L., Chou, S. P., & Grant, B. F. (2009). Transitions in and out of alcohol use disorders: Their associations with conditional changes in quality of life over a three-year follow-up interval. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 44(1), 84–92.

de Bruijn, C., van den Brink, W., de Graaf, R., & Vollebergh, W. A. (2006). The three year course of alcohol use disorders in the general population: DSM-IV, ICD-10, and the craving withdrawal model. Addiction, 101(3), 385–92.

Hasin, D. S., O’Brien, C. P., Auriacombe, M., Borges, G., Bucholz, K., Budney, A., …Grant, B. F. (2013). DSM-5 criteria for substance use disorders: Recommendations and rationale. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(8), 834–51.

Hoffmann, N. G., & Kopak, A. M. (2015). How well do the DSM-5 alcohol use disorder designations map to the ICD-10 disorders? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 39(4), 697–701.

Kopak, A. M., Hoffmann, N. G., & Proctor, S. L. (2015). A comparison of the DSM-5 and ICD-10 cocaine use disorder diagnostic criteria. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 13(5), 597–602.

Kopak, A. M., Metze, A. V., & Hoffmann, N. G. (2014). Alcohol use disorder diagnoses in the criminal justice system: An analysis of the compatibility of current DSM-IV, proposed DSM-5.0, and DSM-5.1 diagnostic criteria in a correctional sample. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 58(6), 638–54.

Kopak, A. M., Proctor, S. L., & Hoffmann, N. G. (2012). An assessment of the compatibility of current DSM-IV and proposed DSM-5 criteria in the diagnosis of cannabis use disorders. Substance Use and Misuse, 47(12), 1328–38.

Proctor, S. L., Kopak, A. M., & Hoffmann, N. G. (2012). Compatibility of current DSM-IV and proposed DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for cocaine use disorders. Addictive Behaviors, 37(6), 722–8.

Proctor, S. L., Kopak, A. M., & Hoffmann, N. G. (2014). Cocaine use disorder prevalence: From current DSM-IV to proposed DSM-5 diagnostic criteria with both a two and three severity level classification system. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 28(2), 563–7.

Proctor, S. L., Williams, D. C., Kopak, A. M., Voluse, A. C., Connolly, K. M., & Hoffmann, N. G. (2016). Diagnostic concordance between DSM-5 and ICD-10 cannabis use disorders. Addictive Behaviors, 58, 117–22.

Rosenberg, H. (1993). Prediction of controlled drinking by alcoholics and problem drinkers. Psychological Bulletin, 113(1), 129–39.

Schuckit, M. A., Smith, T. L., Danko, G. P., Bucholz, K. K., Reich, T., & Bierut, L. (2001). Five-year clinical course associated with DSM-IV alcohol abuse or dependence in a large group of men and women. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(7), 1084–90.

Stea, J. N., Yakovenko, I., & Hodgins, D. C. (2015). Recovery from cannabis use disorders: Abstinence versus moderation and treatment-assisted recovery versus natural recovery. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29(3), 522–31.

van Amsterdam, J., & van den Brink, W. (2013). Reduced-risk drinking as a viable treatment goal in problematic alcohol use and alcohol dependence. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 27(11), 987–97.

World Health Organization (WHO). (1992a). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th revision (ICD-10). Geneva: Author.

World Health Organization (WHO). (1992b). The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: Author.

World Health Organization (WHO). (1993). ICD-10, the ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: Diagnostic criteria for research. Geneva: Author.

Previous Article

Substance Use and the Asian Client

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.