LOADING

Share

Chemical dependency counselors often recognize that a personal network approach is helpful in understanding how people enter, stay, make, and maintain gains in treatment. Because support from family members, friends, and peers in treatment can help maximize the recovery process, establishing network resources is often a treatment goal and part of the relapse prevention plan for women in treatment (Covington, 2002). However, building and changing women’s networks to be more supportive of sobriety can be a challenge because women often enter treatment with very little personal network support, and are often surrounded by many substance-using network members, including their partners, family members, and friends (Grella, 2008; Savage & Russell, 2005). In fact, women are likely to have first used alcohol and/or drugs with family and/or friends (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2009).

In residential treatment, women are separated from their usual environment and daily interactions; during treatment they meet and interact with a new set of people, professional staff, as well as peers in treatment and self-help programs. While this might be an initial advantage, little is known about whether network changes that take place in treatment carry over outside of treatment. Intensive outpatient treatment also provides a chance for women to interact with a new network of professional staff and peers in treatment and self-help programs—at the same time, they are also able to interact with their pretreatment network of family and friends. Our research examines women’s personal networks over time to determine if women’s networks changed or if they stayed the same during and following a treatment episode. The primary purpose of our study was to compare changes in women’s personal networks for those in residential versus outpatient settings; we examined changes in network composition, in the support provided from the network and in network structure. We felt that this type of study would provide information to develop network-based interventions that would be most appropriate for women in residential versus outpatient settings.

Study Design and Sample

Our sample consisted of 377 women who volunteered to become part of the Women’s Network Project, a federally funded study of the role of personal networks in posttreatment functioning. The women had all begun treatment in one of three inner-city, county-funded women’s substance abuse treatment programs: two intensive outpatients (n = 258) and one residential (n = 119) in Cleveland, Ohio. Their age was thirty-six years old on average. Sixty percent identified as African American and 41 percent had less than a high school education. The majority were on welfare assistance. Forty-three percent had experienced homelessness at some time in their lives, and 45 percent reported current legal involvement.

Information was collected from the women in face-to-face interviews conducted by trained research interviewers at one week (T1), one month (T2), six months (T3), and twelve months (T4) after treatment intake. Women who participated in the study received a $35 gift card for each interview. All participants signed a written, informed consent and a certificate of confidentiality was secured from the National Institute of Health (NIH) to further protect the confidentiality of the information collected (see Tracy et al., 2012 for further information on the larger study). Overall retention of the sample in the study was good; 81 percent of the women returned for both the six- and twelve-month interviews.

Data Collection

We used a software program EgoNet (McCarty, 2002; McCarty, Molina, Aguilar, & Rota, 2007) to collect personal network information.

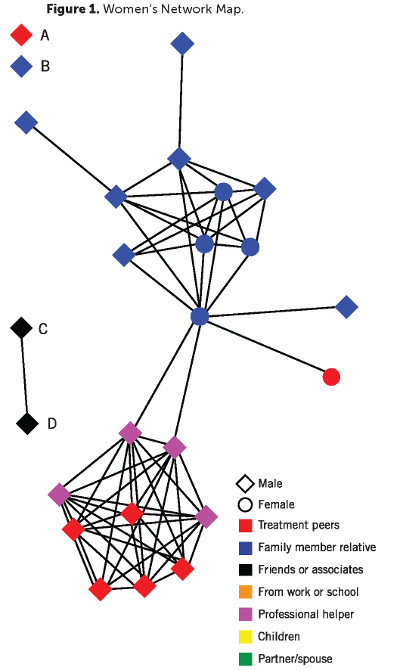

The first step using EgoNet was to list twenty-five people known by the women over the past six months. We then asked how they knew each person listed, whether or not each person used alcohol and/or drugs, and whether or not that was someone with whom they “had used alcohol and/or drugs.” We calculated the total number in the network of treatment related people (combining the number of professional helpers and the number of peers from treatment and self-help programs), the number of people using substances (alcohol, drugs or both), and the number of people with whom the woman reported as having used alcohol and/or drugs.

We also counted the number of people reported as almost always available for concrete (“giving you a ride or loaning you money”), emotional (“being there for you or listening to you”), and sobriety support (“give you support to stay clean”).

Using EgoNet, we also asked for each unique pair “What is the likelihood that person one and a person two talk to each other independently of you?” EgoNet then calculates the following relating to how the network is organized: the number of components, meaning connected groups within the network; the number of isolates, meaning people not connected to any one else; and the density score, between zero and one, which relates to a measure of cohesiveness.

We also assessed a number of other factors, which were either empirically or theoretically related to personal network composition, support or structure. At one week after treatment intake, we assessed the presence of co-occurring mental disorders, trauma symptoms associated with childhood and/or adult traumatic experiences, treatment motivation, and previous substance abuse treatment, along with demographic variables of age, race, marital status, and education. Also, at all four interview time points, we assessed abstinence efficacy (confidence to abstain from alcohol and drugs across high-risk situations), treatment status (in a treatment program vs. out of treatment), and alcohol or drug use in the past thirty days.

Findings

Residential treatment women entered treatment with a more limited support system as compared with women who began outpatient treatment. They had more people they had “used alcohol and/or drugs with,” more substance users, which added up to 40 percent of their network, and fewer people from treatment programs or self-help groups. They also had less social support availability. This could be due to the county referral and placement process, in that women with less supportive environments were considered more appropriate for residential treatment (American Society of Addictive Medicine, 2007). While some of these differences disappeared over time, women in residential treatment—as compared with those in outpatient treatment—continued to have significantly lower numbers of people providing concrete support at the six and twelve month interviews. They also continued to have a higher number of substance-using network members at the twelve month interview. This suggests that women entering residential treatment have a less supportive network to begin with and that they may continue to have problems mobilizing a network supportive of sobriety over time following treatment.

Residential treatment women in this study did show some improvements in their networks over time; they reported an increasing number of professionals and peers from treatment and a decreasing number of people with whom they had used substances over time. They also achieved a significant reduction in numbers of substance users remaining in their networks by six months, but not at twelve months. However, the networks of women in intensive outpatient treatment remained largely the same over time in terms of people from treatment, substance users, and those with whom they used alcohol and/or drugs. This indicates how difficult it can be to eliminate substance users from a network, particularly when, as is the case for many women, the substance users are family and relatives. Over time, both groups of women experienced higher levels of concrete, emotional, and sobriety support, but residential treatment women continued to have less concrete support as compared with the outpatient group. In terms of network structure, women in both treatment modalities reported greater network density over time, indicating that their networks were more interconnected and cohesive. The number of isolates—people not connected to anyone else in the network—decreased over time only for women in intensive outpatient treatment programs.

We examined a number of other treatment and clinical factors which could account for network changes over time. As expected, being in treatment at the time of the follow up interview was related to a higher number of treatment-related people in the network. Reflecting the well-established connection between trauma and substance use, higher trauma symptoms among the women in this study were associated with greater numbers of treatment-related people, as well as more substance users and more people with whom alcohol and/or drugs were used. Higher treatment motivation at one week after treatment intake was associated with a lower number of substance users over time and greater numbers of emotional support providers. Greater abstinence self-efficacy was associated with having more treatment-related people, emotional support providers, and sobriety support, but correspondingly with a lower number of substance users and people with whom alcohol and/or drugs had been used.

While we cannot say with certainty that treatment programming caused the changes we observed in personal networks over time, we did notice that many changes occurred between our first and second interviews, during the early phases of treatment. Overall findings suggest that network composition, support, and how the network was organized are important elements for practitioners to assess not only at initial treatment intake, but ongoing during treatment and recovery. Assessing personal networks early on could help identify women most in need of assistance with their networks. Assessing personal networks on an ongoing basis allows women to notice the way in which their recovery influences their network relationships and provides a means to measure change over time. We found that the women who participated in our study appreciated the opportunity to take a detailed look at their personal networks; for some it was the first time they were really honest about their relationships and over time they began to see that a woman’s recovery could be measured, as one participant noted, “by the company she keeps” (Brown, Tracy, Jun, Park, & Min, 2013). You might ask what difference these network changes make for treatment outcomes. While we do not have all the answers, we did find that those women with a greater number of substance users in the network at the six month interview were more likely to relapse into substance use over twelve months. We also found that less support from friends also increased the likelihood of future substance use. In terms of network structure, higher network density, and higher number of non-substance-using network isolates lowered the odds of substance use (Tracy, Min, Park, & Jun, 2013).

Practice Implications

Some practice implications that can be suggested based on our findings include:

- Help women, particularly in residential treatment programs, to disentangle themselves from substance users in their networks and to disconnect from people with whom they had used before in an assertive yet respectful manner. Communication skills training and role-play practice may help women learn to deal with and plan for difficult interactions and settings.

- Recognize that these substance users may be family members who provide other types of support to women, making it even harder to disconnect and so a strategy of managing relationships might be more realistic over the long haul than breaking ties completely. For example, while it may not be possible to cut off a relationship it may be helpful to learn how to cut a stressful phone call short if such calls serve as triggers for use.

- Take advantage of those network members who serve a bridging role within the network as these people can help with information flow and communication, such as that needed to convene a family meeting. Assessing personal network relationships yields important information about who serves what roles in the network; this information is helpful not only to practitioners but to female clients as well.

- Interventions that build connections among network members may be helpful as higher network density was predictive of less likelihood to use substances. The very act of asking about personal network members provides insight as to how people are connected. Other ways to build or develop connections include family meetings, educational meetings, referrals to self-help groups, and alumni groups.

- Isolates, particularly those who are non-substance-using, may be a strength to cultivate in networks of women with substance use disorders. The addition of non-substance-using network ties may be achieved through participation in Twelve Step self-help groups, such as AA or NA, as well as through alumni groups.

We continue to be interested in the ways in which personal networks can support treatment efforts and how a growing understanding of the ways in which networks help, or do not help, recovery can lead to network interventions to meet the needs of women in residential and outpatient treatment settings.

Acknowledgements: The project described was supported by award number R01DA022994 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIDA or NIH.

References

American Society of Addictive Medicine. (2007). ASAM PPC-2R patient placement criteria for the treatment of substance-related disorders. Chevy Chase, MD: Author.

Brown, S., Tracy, E. M., Jun, M. K., Park, H., & Min, M. O. (2013). “By the company she keeps”: Client and provider perspectives of facilitators and barriers to personal network change for women in treatment for substance dependence. Paper presented at the Society for Social Work Research (SSWR), San Diego, CA.

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. (2009). Substance abuse treatment: Addressing the specific needs of women: Treatment improvement protocol (TIP) series, no. 51. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Covington, S. S. (2002). Helping women recover: Creating gender-responsive treatment. In S. L. A. Straussner, & S. Brown (Eds.), Handbook of women’s addictions treatment (pp. 52–72). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Grella, C. E. (2008). From generic to gender-responsive treatment: Changes in social policies, treatment services, and outcomes of women in substance abuse treatment. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, November(Suppl 5), 327–43.

McCarty, C. (2002). Structure in personal networks. Journal of Social Structure, 3(1).

McCarty, C., Molina, J. L., Aguilar, C., & Rota, L. (2007). A comparison of social network mapping and personal network visualization. Field Methods, 19(2), 145–62.

Savage, A., & Russell, L. A. (2005). Tangled in a web of affiliation: Social support networks of dually diagnosed women who are trauma survivors. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 32(2), 199–214.

Tracy, E. M., Laudet, A. B., Min, M. O., Kim, H., Brown, S., Jun, M. K., & Singer, L. (2012). Prospective patterns and correlates of quality of life among women in substance abuse treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 124(3), 242–9. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.01.010

Tracy, E. M., Min, M. O., Park, H., Jun, M. K., & Brown, S. (2013). Personal networks and substance use at twelve-month post treatment among dually diagnosed women. Paper presented at the Society for Social Work Research (SSWR), San Diego, CA.

Editor’s Note: This article was adapted from an article by the same authors previously published in the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment (JSAT). This article has been adapted as part of Counselor’s memorandum of agreement with JSAT. The following citation provides the original source of the article:

Min, M. O., Tracy, E. M., Kim, H., Park, H., Jun, M., Brown, S., . . . Laudet, A. (2013). Changes in personal networks of women in residential and outpatient substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 45(4), 325–34. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2013.04.006

Previous Article

Field Reports

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.