Over the past three decades the addiction treatment field has shown a marked interest in using experiential methods for treating psychological trauma. A unique feature of our field is the camaraderie that healers share with those they are helping. Many in our field come from lives that have been deeply affected by addiction and have experienced firsthand the trauma that addiction engenders not only in the addict but in those who love, need or are in close relationship with the addict. We as healers and as people seeking healing have collectively recognized the profound and life-changing effect of forms of healing that go beyond talk. “Fundamentally, words can’t integrate the disorganized sensations and action patterns that form the core imprint of the trauma,” says Bessel Van der Kolk (Wylie, 2004). “The imprint of trauma doesn’t ‘sit’ in the verbal, understanding part of the brain,” he continues, “but in much deeper regions—amygdala, hippocampus, hypothalamus, brain stem—which are only marginally affected by thinking and cognition” (Wylie, 2004).

The part of our brain that orders and reflects upon experience is temporarily offline when we’re overwhelmed by psychic pain and shock. The psychic fear, pain, rage, and helplessness of those moments sinks into deeper regions of the brain along with the sights, sounds, smells, and feelings that surround the experience. What is unavailable to us is the through line, the narrative. What we do have stored within us is a jumble of sense impressions and emotions that sit within us waiting to be triggered to the surface through life circumstances that trigger sense or feeling memories. In the case of relational trauma, it is relationships that often act as the trigger. A change in mood, raised voices, a tense atmosphere or even darting eyes can trigger the hidden wounds of relational trauma that occurred in one relationship, to be felt and even expressed or acted out in subsequent relationships. In this way, unresolved pain from the past can get seamlessly imported into the present and pain can become intergenerational. Additionally, this entire process may occur without our awareness of what is happening; that is, we do not know that we don’t know.

Therefore, we ask a patient that most baffling question, “Tell me about your trauma and how it made you feel,” we may well be faced with the blank stare of someone who, for the life of them, cannot. The defenses that we mobilize to make a moment less overwhelming and frightening are designed by nature to block the emotional experience of the moment. As we said earlier, our thinking mind shuts down momentarily and we become all limbic, all sensorial and physiological action. When we’re very frightened or overwhelmed, we’re charged with the action chemicals and blood flow to get us to act without thought, to flee for safety or run headlong into some form of fight. The last thing we’re doing is consciously reflecting on how the moment makes us feel. In fact, that is what our defenses of numbing and splitting are essentially for, to temporarily make us unaware of what we’re feeling so we can continue to function because our thinking mind is not ordering our experience of the moment as it normally would. Later, as we move away from immediate threat of the frightening circumstance, the contents or significant parts of that moment may be unavailable to us on a conscious level. If a patient feels put on the spot to answer a question that they have no good answer for, they may well say what they think we would like them to say. While this may satisfy the expectations of the moment, it may do little to heal the particular wound of the person who is still holding pain. While words can be a royal road to freedom, they need to be the right words associated with the right nuanced feelings. They need to arise directly from the inner experience of the client, tailored and shaped according to the inner impulse that longs to find expression. My experience in working with the healing of trauma is that words that truly need to be said in order for a patient to find his or her voice are often come upon delicately, with tender trepidation. They can be barely audible as often as they reveal themselves as part of a catharsis of pain or rage. They are often hard won and they emerge when something in the environment—whether another person’s story, their face, attitude, voice or shift in mood—triggers them. Often times triggering simply leads to frozenness on the part of a client and words remain unsaid.

When asked, seven years ago by Velvet Mangen, to create a model that could be used in her treatment centers I was challenged with coming up with an experiential approach that could be easily taught to therapists and effective with patients that was contained and predictable. Much of what I incorporated were those processes I had developed that I knew worked and had been working over a long period of time. Essentially I have been slowly developing and implementing my own hybrid of psychoeducational exercises, “psychosocial metrics,” that integrate current research on neuroscience and attachment with experiential approaches and sociometry, part of J. L. Moreno’s triadic system of psychodrama, sociometry (concretized group dynamics), and group psychotherapy. I had developed the “Trauma Time Line” and “Feeling Floor Checks” in response to requests of trainees to have vehicles through which to address trauma issues that were contained and experiential. Psychodrama, though powerfully healing in treating trauma, was less easy for clinicians to learn and feel comfortable doing. Therefore my model has two levels, the first is based on contained experiential exercises and the second level uses psychodrama. However, level one is very adequate in and of itself and can be incorporated into existing therapeutic models. Clinicians can choose which processes or exercises to use and where to apply them. These exercises act as “safe triggers” that allow clients to revisit their triggered parts in a contained, group process. The warm up of the exercise both focuses healing and triggers emotion that can be felt, articulated and shared in a supportive, relational context. Feelings can be regulated over and over again through translating them into words and sharing them with others who are doing the same thing. Clients learn experientially and thus are more easily able to incorporate the skills of emotional regulation.

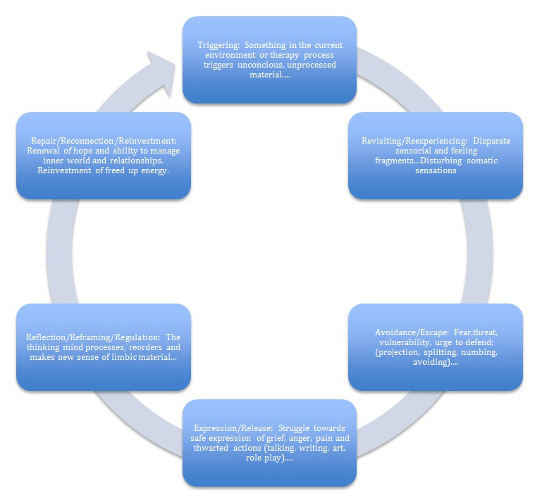

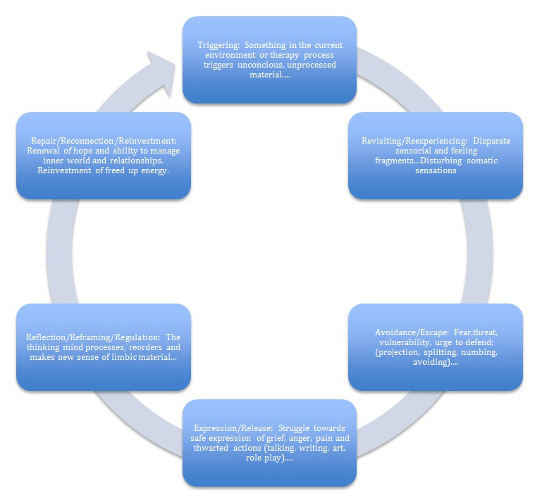

The Experiential Therapy Healing Cycle

Psychosocial metrics are psychoeducational processes that are based on the principals of J. L. Moreno’s sociometry. They are essentially a combination of experiential processes that are informed by current research on attachment and neuroscience. For example in “The Feeling Floor,” one is asked to actually choose, walk towards, and stand next to a feeling they may be having. This very simple process helps patients to get up out of their chairs, tune in with themselves, focus in on what’s going on in their inner world and own that particular feeling. They may find themselves standing in the same place as others, which gives them an immediate point of identification and spring board for the kind of sharing that has common ground. Having done this they take a next step in developing both emotional intelligence and literacy as they describe what their inner experience is in words so that they can better understand it themselves and communicate it to others. They stand and listen as others go through a similar process; they can further clarify their feelings by identifying or differentiating from others. Throughout this experience their emotions are churning around inside of them and becoming more felt and conscious; they are revealing and reflecting on what is in their inner world. At some point in the exercise they can connect with others by sharing more intimately in pairs or clusters with those standing near them or with someone in particular who said something that resonated with them. If the papers on the floor are describing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, they become aware of and educated about how those symptoms actually manifest for others. If the questions on a spectrogram involve symptoms of grieving, they learn about the dynamics involved in the grief process. Their own grief is triggered through a contained and slow process that allows the feeling to be felt, to grow in intensity, be translated into words, shared with others, and dissipated in intensity through processing it. This whole process constitutes a path of emotional regulation, clients who may have avoided certain feelings because they felt unmanageable can experience a way of managing them and right-sizing them. Not only do they see the actual emotions or symptoms, but they hear how they might manifest for a variety of people. Healing and learning happen simultaneously in a relational environment.

Taken from Relationship Trauma Repair (RTR): Therapist’s Guide by Tian Dayton

Additionally, there are positive words and criteria that can be equally taken hold of and shared. Healing isn’t just about understanding our pathology, but about marshaling and owning our strengths as well. Owning both pain and strength in a group context helps to solidify these qualities within the self. According to Van der Kolk, “If clinicians can help people not become so aroused that they shut down physiologically, they’ll be able to process the trauma themselves” (Wylie, 2004). Experiential psychoeducational exercises, journaling, guided imagery, and psychodrama can stimulate memories and provide a safe arena in which they can be shared and processed.

The exercises in relational trauma repair (RTR), particularly in level one, are very basic and clients soon learn their progression by heart so that they can focus more exclusively on their own experience of self and self in relation to others. Clients in treatment are in a highly sensitive state and often worry about getting therapy “right”; making RTR simple helps to lift this anxiety so that clients can experience a healing process that becomes organic and familiar. Additionally, because the process encourages autonomy, clients have an easier time incorporating the skills of self-regulation and emotional literacy within themselves. They are less dependent on the interpretation of the therapist and get more practice in tuning in on and developing their own inner awareness.

Knowing the basic process also begins to introduce an almost game-like quality that clients can relax into, which allows the emotional climate of the group to run the full gamut from momentary catharsis or tears, to lighthearted laughter. The energy in the room can move from deeply moving and serious to an easy and playful sense of camaraderie. Learning to laugh is as important as learning to cry and both run through the same body/mind channels. A catharsis of laughter is every bit as healing as a catharsis of pain and developing the ability to play and celebrate life is as important as developing the ability to process pain. I encourage my groups to laugh as well as cry and to play right alongside doing deep work. Most groups find their way instinctually to perceiving which moments to bear witness to respectfully and quietly and which moments to lighten. If they are off kilter, that too is useful for healing; they can recalibrate their responses according to what feels appropriate to the rest of the group.

Groups have a magical way of intervening on the most tender corners of our minds and hearts. Through sharing one another’s stories, feelings are pulled from their hiding places towards the surface. The dynamics of identification, transference, and projection make groups a hot bed of dynamics. All at once you feel your mother is sitting in the chair across from you, your father has just opened his mouth, your sibling is there to buddy up with you for safety or taking the lion’s share of the therapist’s attention and gobbling it all up for himself. Relying on the warm and alive dynamics that are part of most groups can bring forth more than enough material to work with. In my experience however, much more can be mined through experiential processes that focus in on the particular issues and dynamics of a given population.

What is Relational Trauma?

Relational trauma is the kind of emotional and psychological trauma that occurs within the context of relationships. Nature evolved the ability to form powerful bonds into our species to insure that partners will pair bond and parents will remain securely enough attached to children until they can thrive on their own. Without this formidable form of bonding, our species would become extinct, baby animals and human children would wander away from parent figures, and parents would forget about their young.

Because we attach so powerfully in order to accomplish this awesome task of people making, when these bonds are ruptured, that rupture can feel traumatizing. Nature rewards connection and punishes disconnection. Our bodies are designed to reward emotional closeness with feel-good body chemicals like oxytocin (“the bonding chemical”) and serotonin. These are the body’s natural mood stabilizers or emotional regulators, built into us to ensure that attachment is a pleasurable and sustainable experience. Emotional rupture, neglect or disconnection, on the other hand, is punished by stress chemicals, like cortisol, that can cause fatigue, nervousness, depression, anxiety or even weight gain. Chronic stress, conflict, abuse, and neglect are distancing behaviors that undermine feelings of closeness, trust, and connection and can contribute to emotional dysregulation. When our environment is chaotic or fear-inducing we may have a hard time staying in emotional balance.

When family relationships feel unsafe or alternate between feeling safe and secure and then suddenly frightening, that is when deep, intimate connection can become woven together with feelings of fear. While relationships represent love and security, they may also and more unconsciously carry the scent of anxiety, pain, humiliation or even abandonment if there has been too much trauma in the home and if that trauma or rupture was never repaired. Difficult circumstances are the norm for anyone, how they are handled is what defines whether or not they feel traumatizing or provide fodder for growth, understanding, and maturity.

Childhood pain can lie dormant for days, weeks, months or even years. We may function on our own perfectly well, but when we form relationships in adulthood, unresolved pain from the past can get triggered and projected onto present day relationships without our understanding of what’s happening. For the soldier with PTSD, a loud sound like a car backfiring can trigger fear and he can interpret that sound as gunfire and tremble, fall to the ground or run. For the person who has experienced family trauma, relationships are that gunfire. The feelings of vulnerability, attachment, and dependence that are part of any intimate relationship trigger unresolved neediness, fear, and pain. We feel small and vulnerable all over again and may overreact in the present to relationship dynamics that bring up fears of humiliation and rupture from the past. In this way our unresolved and unconscious pain from the past interferes with our relationships in the present because what we don’t know can still hurt us. What we can’t consciously feel can still have great power over us. Working with relational trauma therapeutically can allow us to use our pain as fodder for inner growth rather than as fuel for continuing dysfunctional relational dynamics. It allow trauma to become a window into new possibilities in life and relationships.

References

Wylie, M. S. (2004). The limits of talk: Bessel Van der Kolk wants to transform the treatment of trauma. Psychotherapy Networker. Retrieved from http://www.psychotherapynetworker.org/populartopics/trauma/485-the-limits-of-talk

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.