Share

The aim of this article is to highlight how organizational knowledge and the experience of providing residential rehabilitation for people with drug and alcohol dependencies can inform the design and delivery of community-based services. It will also highlight how the development of these services can play a critical role in preventative and early intervention opportunities, protecting adults and children from harm whilst expediting the pathway to recovery or a life of independence.

Introduction

The Nelson Trust is a charity that works with and beyond addiction to inspire change. We lead and innovate where the constellation of substance misuse, trauma, offending, and abuse lead to severe and multiple deprivation, which affects whole families and often perpetuating problems from one generation to the next. We enthusiastically champion our belief in the capacity for personal change and growth and promote the values of lived recovery from addiction. We look beyond addiction to develop support programs to address areas of people’s lives that keep them entrenched in or at risk of addiction and dependence. We seek a world where no people need to become addicted; and if they do, they know that there is a way out before it destroys them.

We run an abstinence-based, residential rehabilitation facility for people with drug and alcohol dependencies. Based in the Cotswolds in England, we have operated for over thirty years and have a forty-four bed capacity across four units. We run a further twenty-three beds across another four units, providing housing for clients requiring support as they transition to independent living. The units work on average with 150 people per year.

The Trust also runs two community-based women’s centers: one in Swindon and one in Gloucester. We will soon open another in Bridgwater. These currently work with approximately 1,250 women a year. The organization has a reputation for working successfully with clients with multiple and complex needs. It has won many national awards and staff have won individual national “Outstanding Achievement” awards in recognition of their passion and commitment.

Background

Typically in 1986, individuals accessing rehabilitation at The Nelson Trust would have been in their late thirties or early forties, would likely have been alcoholic, would have been three times more likely to have been male, would probably have a mild to moderate affective disorder, would have been educated until at least the age of sixteen, would have a defined occupation or profession, would have little or no meaningful contact with the criminal justice system, would retain family contact and support (though sometimes the imminent breakdown of a significant relationship would be the precipitating event that directed individuals towards support), and would have a home to return to.

In 2018, clients typically present in their mid to late twenties; are mostly poly-drug-users; are just as likely to be male as female; often have co-occurring mental health problems including affective, eating, and psychotic disorders; often have been poorly educated with little or no employment history; will have frequent contact with the criminal justice system for low level offending; have unstable family relationships; and have no meaningful home to return to (that is, while all are not strictly homeless, to return to the chaotic environment they entered treatment from would be wholly incongruous with an ambition for abstinence-based recovery).

In the years between 1986 and 2018, the organization has grown and adapted to respond to the changing needs of the clients who access the service. For example, in 1999 its employment, training, and education resource began life as an afternoon slot where a member of staff offered advice on how to access local college courses. It now consists of four enterprises: a cafe in the center of Gloucester, a drug- and alcohol-free venture in Cheltenham, a small business doing building and maintenance work, and an academy offering accredited training courses for clients. Together, these offer employment and training opportunities, and because of their public profile, work to dismantle the stigma associated with drug and alcohol dependence. The first of these, the cafe in Gloucester, had an independent social return on investment analysis carried out by the Public Health Institute at Liverpool John Moores University. It found that for every £1 invested, there was a return of £9.71 of social value (Harrison et al., 2017).

Another example is the women’s only service which began in 2003. Following the United Kingdom National Outcome Research Study (Gossop et al., 1997; Gossop et al., 2003), client retention and planned completion of treatment episodes were seen as a proximal indicator of a likely outcome of sustained recovery at five-year follow-up.

Research and Review Findings

In 2003, we reviewed a cohort of our treatment population who had not completed treatment. The usual reason for noncompletion is relapse while in an abstinent setting. However, there were a number of people who were leaving in relationship with another and they would usually relapse further down the line sometimes with fatal consequences. For women, it looked disproportionately high, as males then made up between 66 and 75 percent of the treatment cohort.

With closer analysis, we discovered that these women shared a number of common characteristics. They tended to have experienced childhood trauma, usually sexual abuse; they tended to have children who were in the care of the local authority or of extended family, and the clients had often been through the care system themselves; they had multiple experiences of domestically abusive relationships; many had mental health problems; some had sex worked to fund their addictions; most had frequent contact with the criminal justice system; most had housing problems; and they also had drug and alcohol issues.

A senior team within Nelson Trust determined that trauma was a significant issue: if we were to reverse the dropout rates, we would need to address it. They also determined that a mixed gender environment was inappropriate, so a women’s only unit was opened in 2004. A trauma-informed approach was developed and we began to establish programs and interventions with the particular cohort in mind. We employed a systemic family therapist to develop a family program, including facilitating genograms. We located a family apartment beside the unit so children could visit and stay overnight in preparation for the women resuming parenting responsibility. We employed more psychotherapists to facilitate resilience as part of the trauma work. Within a year, the women’s only unit was achieving better retention rates than the mixed gender unit.

In 2007, the United Kingdom government published The Corston Report about the female prison population, which had been commissioned to examine the unacceptably high number of women committing suicide in prison and who had been imprisoned for very low-level and nonviolent offenses (Corston, 2007). Around 60 to 70 percent of these women would re-offend within a year. What was interesting about the report was it came to very similar conclusions as Nelson Trust had: women with multiple vulnerabilities need to be supported with an awareness of and in all their areas of need. Along with Corston, we had identified nine pathways of need:

- Accommodation

- Employment, training, and education

- Physical and mental health

- Relationships with children and families

- Drugs and alcohol

- Finance, benefits, and debt

- Attitudes, thinking, and behavior

- Domestic abuse and sexual violence

- Sex work, prostitution, and trafficking

Not all women accessing the service have support needs on all the pathways, but all women have needs on a number of pathways, usually four or five. We categorize the needs by determining which are critical (usually accommodation or health), which are current (usually drugs and alcohol), and which are ongoing (usually children and families). A support plan is constructed accordingly and regularly reviewed.

In 2016, the women’s only unit was evaluated by the National Addiction Centre at King’s College London, London (Tompkins & Neale, 2016). The research explored how and why the service appeared to be helping female drug and alcohol users with a history of trauma and which components of the service worked or did not work in producing measurable outcomes. Findings suggested that when trauma-informed treatment worked, women remained abstinent from alcohol and other drugs, improved relationships with others, and improved their physical, mental, and psychosocial health and well-being. Additionally, women seemed less affected by previous traumas, recognized their past experiences as traumatic, appreciated how trauma had affected them, and felt more equipped to manage trauma- and substance-related triggers. Once abstinent, women no longer engaged in criminal activities and they felt more positive about their future. Women felt safe in an exclusively-female environment and treatment appeared to be most successful when clients felt safe and when they developed trusting and close therapeutic relationships with staff. Developing this relationship was easier when staff had lived experience of addiction, believed in the women’s ability to change, and when they listened.

Reducing Reoffending

In 2008, we came to the attention of the Ministry of Justice because the cohort of women we worked with were not reoffending if they completed treatment. If they did not have treatment, they were 60 to 70 percent more likely to re-offend within the first year of release from prison. The same profile of women were victims of high suicide rates and self-inflicted harm within the penal system, and so in 2009 we were asked if we could develop a service in the community, but under the auspices of a criminal justice pathway (i.e., funded by criminal justice agencies and focused on reducing reoffending).

In February 2011, we opened a women’s center in Gloucester, building on and adding to a network of about forty women’s centers that already existed across the UK. The evidence demonstrating the efficacy of women’s centers that work with women with multiple vulnerabilities has been well documented (Page & Rice, 2011). There is also evidence from the Ministry of Justice data lab that women’s centers have a significant statistical impact on reducing reoffending (Ministry of Justice, 2015).

We set about developing a holistic, one-stop shop service—gender-specific and trauma-informed—where we sought to deliver support along all of the pathways or provide support along some of the pathways by bringing in partner agencies. With this model, we engage women if they are arrested for a petty offense and before they move along the criminal justice pathway to court. We engage women who have reached the court stage, and some are offered support at the women’s center instead of a custodial sentence. We engage women who are incarcerated, identify their needs, develop a support plan, meet them at the gate on release, and bring them to the women’s center to begin implementing the support plan.

We also engage women who are identified as being at risk of offending. Working outside the criminal justice system has enabled us to understand that the label women pick up is a consequence of which service door they walk through. She can be identified as a woman with mental health issues, a woman with a drug and alcohol problem, and so forth, though many women have multiple and complex needs. Unfortunately, the UK public health, mental health, and social care systems are commissioned in silo fashion, so they are not designed to respond to multiple and complex needs.

Women and Children

In 2010, the UK government began implementing a policy of austerity. Massive funding cuts made it increasingly difficult for women with drug and alcohol dependencies to access residential treatment. All the women we worked with in community services were reliant on public funding, so we knew we would need to bring significant influence to bear on the referral pathway.

We knew the women were snared in a toxic trio of mental health, domestic violence, and substance misuse issues. Related issues manifested in the remainder of the nine pathways. These women also had children, and we knew from evidence on adverse childhood experiences that these children were likely to have experiences that perpetuated an inter-generational recycling of the same problems (Bellis et al., 2015). We understood this as a real opportunity to achieve early intervention and preventative outcomes.

For example, in 2016 a serious case review anonymized as “Philip” was published by our local children’s services. Serious case reviews are undertaken when abuse or neglect are known or suspected, or a child dies or is seriously harmed, and there are concerns about how professionals and organizations worked together to protect the child (GSCB, 2016). In this instance, a three-year-old boy suffered broken ribs and a perforated intestine and had to be rushed out of the county for life-saving treatment. At the time, the mother was on a substitute prescription (she had been for six years and was reported in the review as still reducing), was a victim of domestic violence, suffered from mental health problems, and was living with a partner who was a heroin addict and a perpetrator of domestic violence. From the review, her drug treatment seemed to consist of a fortnightly appointment to pick up a prescription and submit a urine sample.

From our point of view, this is a tragic example of how things could be done differently. While there is no guarantee that the incident would have been avoided, we believe that had she been accessing the women’s center for her drug treatment, the following might have made a difference: the center has crèche facilities, making the service more accessible; a member of staff may have picked up signs and symptoms earlier; the mother would have had a dedicated keyworker available for assertive outreach giving us an insight into her home life; she could have accessed a perinatal mental health service at the center; she could have participated in a general health and well-being program; she could have attended a domestic abuse program; crucially, she would have attended the center with other mothers who had begun to turn their lives around, offering hope and the belief that change could be achieved.

Sex Workers

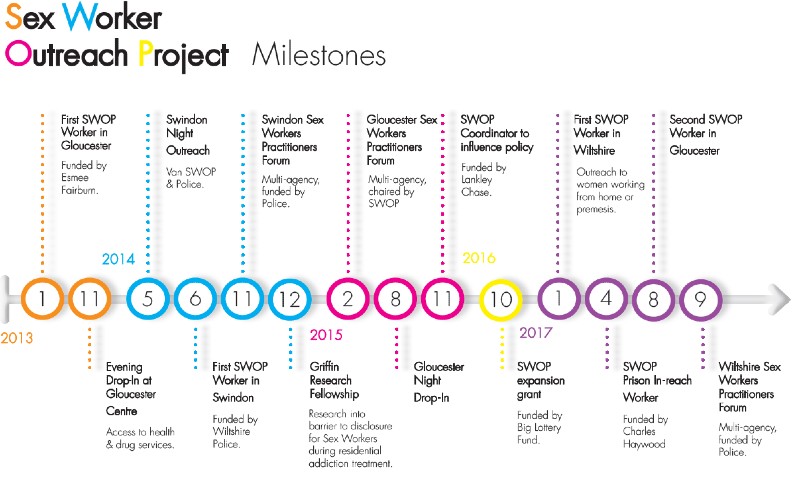

In 2013, we opened another women’s center in Swindon and part of the services were funded by the local Police and Crime Commissioner (PCC) in order to develop a sex worker outreach project (SWOP) for street sex-working women. PCCs are elected every six years, and there are forty across England and Wales. They are responsible for the totality of policing, ensuring the needs of their communities are met.

As we established the service, we learned that agencies working with SWOP clients traditionally did not have a great working relationship with the police. Anecdotally, this seemed to be around sustaining trusting relationships with the clients, as their experiences of the police were often negative—particularly when it came to reporting crimes that had been committed against them. Police would sometimes perceive the women as being unreliable witnesses and that their complaints lacked credibility, while the women felt the police did not believe them or, even worse, believed they got what they deserved. The women would be reluctant to report assaults to the police for fear of not being taken seriously and they considered assaults as “part of the job.”

An exception was where there was a statutory duty on agencies to report safeguarding concerns, usually related to children. However, evidence suggested that every woman doing sex work had a safeguarding concern either in relation to increased risk of murder (Ward, Day, & Weber, 1999) or multiple rapes (Roe-Sepowitz, Gallagher, Hickle, Loubert, & Tutelman, 2014). We made a controversial decision to work very closely with the police, sharing relevant information so the workers providing the outreach support had a female police vice liaison officer as part of the team. Support staff had direct radio contact with the police, and the police also gave the team a van they could use as a mobile unit for night outreach.

Simultaneously, the support team worked closely with the women, encouraging them to report crimes while making sure they were treated like any other victim. This meant that every single report of violence by the Swindon women was followed up and a number of convictions for serious offences were secured, with some attracting long custodial sentences.

The team also worked with the police to set up a conditional referral to the women’s center when women were arrested. Outreach workers realized the current sentence for soliciting (i.e., a fine) was counterproductive, as it only encouraged further sex work to pay the fine. Following joint promotional work by the police and Nelson Trust, magistrates now have at their disposal conditional cautions and engagement and support orders which sentence women to attend the women’s center in place of a fine.

In addition, the team established two local forums. One was a practitioner’s forum—multi-agency representatives met monthly to see how we could coordinate practical support for the women such as housing and access to community drug and alcohol services. The second was a quarterly strategic forum where senior policymakers and commissioners met to determine what systemic changes need to be made to ensure the practitioner forum worked effectively.

The shape the service began to take was one where we assertively outreached to engage and direct women towards the center to provide support with the ultimate aim of encouraging the women to disengage from street sex-working activity.

It was a good illustration of where our abstinence principle was applicable and transferable; the message was “if you abstain from this behaviour, we will be in a much better position to support you into a life free from the risks you currently face and with the liberty to determine what kind of life you want to live.” The capacity for change is a founding principle of The Nelson Trust. We believe people can change if they receive the right support at the right time.

As we developed the support pathway for sex workers in the community, one of the staff in our residential setting sought to understand the issues facing individuals in treatment who had done sex work to fund their addiction. She explored the barriers and facilitators of disclosure for sex-working women in residential treatment. The research took place over a year and was finalized and published as a research paper in June 2015 (Tate, 2015).

The scope of the research was framed by attempting:

- To ascertain the prevalence of awareness within UK drug rehabilitation services of the number of sex workers in their services through their referrals, admissions, and assessment procedures

- To explore the meaning, barriers, and enablers of peer disclosure of sex-working history in a residential treatment setting

- To explore the meaning and experiences of disclosure of sex workers posttreatment at varying stages of recovery/relapse

The “Losing My Voice” research paper (Tate, 2015) made three recommendations for those providing residential drug and alcohol treatment to sex-working women:

- Sensitive allocation of support staff for sex workers is crucial to relationships being fostered where disclosure can take place. Female staff are essential for women to feel safe and understood.

- Specific workshops, group work, and assignments are critical to the process so that disclosure is not only encouraged, but supported and transitioned into a process of further healing.

- Opportunities should be established for women to share experiences in a safe environment, allowing them to develop perspective and resilience. Group settings that encourage women with enough agency to explore this topic would be beneficial.

As a direct response to these recommendations and the findings of the study as a whole, three gender-specific and trauma-sensitive interventions were developed:

- The Griffin Program: for women in residential treatment who have an identified sex-working history, who are not actively sex working, and who are abstinent from substances

- The Pegasus Program: for women in the community who are actively sex working and do not have to be abstinent from substances. It is deliverable on a one-to-one basis or as a group activity

- The Phoenix Program: for women three or more years in recovery who are still experiencing invasive and pervasive shame around sexual dysfunction in current sexual relationships

The core concepts of the three programs are research-based and incorporate principles of healing trauma (Covington & Russo, 2011), awakening sexuality (Covington, 2000), creating an ex-role (Månsson & Hedin, 1999), and tools for building safety (Navajits, 2002).

The working premise is that the sex-worker identity is a form of split-self developed to allow women to sex work in what is essentially a dissociative state—to enable them to perform and manage the emotional reality of their experiences. When coupled with dehumanization from their clients and stigma from the outside world, the sex-worker identity is solidified.

Sex work plays out for women long term in the same way that sexual trauma does. However, this often gets missed when women have not experienced childhood sexual trauma, so the presenting symptoms often do not make sense to practitioners as being linked to historical sex working.

The research illustrated that women exiting sex work and/or finding recovery is not enough to deconstruct the sex-worker identity and that it permeates for extensive periods of time. For example, one woman interviewed was twenty-two years in recovery and still experiencing ongoing effects.

All three programs exist to create safety, to explore the individual components of each woman’s sex-worker identity, and to deconstruct the foundations using connectedness, shared experience, reframing, sexual development awareness, relationship, and sexual reconnection tools. Timelines are created that examine when transactional sex became a reality (usually before sex working officially began) and the adolescent experiences that may have shaped a woman’s later decision to sex work, and explore the concept of choice and whether they really had one.

A program participant shared, “I never grew up just wanting to be a sex worker! Thinking about my experiences that shaped my decision to sex work opened my eyes to ‘how I got there’, which in turn subsided some of the guilt and shame.”

Secondary elements of each program aim to rebuild a recovery identity or connect the existing recovery identity with a fresh perspective on sexuality and relationships.

A core aim of each program is to allow women a safe holding space to explore their internal realities around sex working while providing emotional and practical support to promote recovery and healing. The shared experience between women directly challenges shame and the belief that they were the only one dealing with these issues.

Summary

Zooming in on the street sex-working pathway for this article appealed as it was the latest area of our work to be independently evaluated. The research was carried out from 2015 to 2018 by Professor Sylvia Walby and Dr. Susie Balderston. The research was funded by Lankelly Chase (a grant-making trust) to share learning and improve future provision. Professor Walby and Dr. Balderston presented their initial findings at a conference in Swindon in 2018.

The final report has yet to be published, but has found that SWOP delivers highly effective crisis intervention on the streets at night and with casework through the day. The service is trauma-informed, gender-specific, and nonjudgemental.

The SWOP advocacy service engages and works with women who are selling sex on the street to build trust and address their immediate safety and survival needs so they are able to move towards being healthy and protected from violence. This pathway works from the point of need on the street. Specialist casework and advocacy assists clients to navigate complex welfare, housing, social care, health, criminal justice, and family court systems. This includes diversion from custody when appropriate and support for mothers and children. The caseworkers then work with clients and other agencies to holistically tackle underlying causes, trauma, symptoms, and their entrenched, multiple, and complex social, health, safety, and justice problems correlated with sex work.

SWOP is achieving exemplary concrete outcomes for extremely marginalized and excluded women at serious risk of violence and harm. SWOP clients often cannot be reached by mainstream or statutory services because of their need for high levels of out-of-hours engagement not provided by commissioning contracts. Other services often exclude or fail to serve sex-working women. SWOP works with partner agencies in order to tackle exclusionary eligibility criteria. Conditionality, lack of gender-specific provision, and stigma can prevent women from accessing the welfare, health, or justice she requires in a timely way.

These women are our most vulnerable and complex clients, most difficult to engage, and when in their chaos more often in danger of violence and assault. This treatment pathway also enabled me to illustrate how we have sought to shape and organize a system to respond to the needs of these women in a way that is effective.

We know that these women do and will have children. We know that these children will witness and be victims of the chaos that surrounds them. We know this will perpetuate the intergenerational cycle of complex vulnerability manifesting at a later date as a mental health, domestic abuse, and drug and alcohol issues.

We know that if we can support these women before they bring children into lives that are fulfilling and meaningful, we can disrupt that intergenerational cycle. If they already have children, then we can intervene earlier and at the very least stop things from getting worse.

Acknowledgments: I am deeply indebted to Professor Walby, Dr. Balderston, Dr. Stephanie Covington; to Marina Fontenla, our data analyst; to Kirsty Tate, our Griffin Fellow; the SWOP team, led by Katie Lewis, who does an amazing job; and the wider team at The Nelson Trust for their energy, passion, and commitment. Any disparities between their views and this article will be my mistake, so I apologize in advance.

References

- Bellis, M. A., Ashton, K., Hughes, K., Ford, K., Bishop, J., & Paranjothy, S. (2015). Welsh Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study: Adverse childhood experiences and their impact on health-harming behaviours in the Welsh adult population. Retrieved from http://www2.nphs.wales.nhs.uk:8080/PRIDDocs.nsf/7c21215d6d0c613e80256f490030c05a/d488a3852491bc1d80257f370038919e/$FILE/ACE%20Report%20FINAL%20(E).pdf

- Covington, S. S. (2000). Awakening your sexuality: A guide for recovering women. Center City, MN: Hazelden Publishing.

- Covington, S. S., & Russo, E. M. (2011). Healing trauma: Strategies for abused women [CD-ROM]. Center City, MN: Hazelden Publishing.

- Corston, J. (2007). The Corston report: The need for a distinct, radically different, visibly-led, strategic, proportionate, holistic, women-centered, integrated approach. Retrieved from http://criminaljusticealliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Corston-report-2007.pdf

- Gloucestershire Local Safeguarding Children Board. (2016). Serious case review: “Philip, (and his siblings, John and Darren).” Retrieved from https://www.gscb.org.uk/media/12924/philip-scr-version-10-301116-final.pdf

- Gossop, M., Marsden, J., Stewart, D., Edwards, C., Lehmann, P., Wilson, A., & Segar, G. (1997). The National Treatment Outcome Research Study in the United Kingdom: Six-month follow-up outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 11(4), 324–37.

- Gossop, M., Marsden, J., Stewart, D., & Kidd, T. (2003). The National Treatment Outcome Research Study (NTORS): Four- to five-year follow-up results. Addiction, 98(3), 291–303.

- Harrison, R., Cochrane, M., Pendlebury, M., Noonan, R., Eckley, L., Sumnall, H., & Timpson, H. (2017). Evaluation of four recovery communities across England: Final report for the Give It Up project. Retrieved from https://www.basw.co.uk/system/files/resources/basw_82546-6_0.pdf

- Ministry of Justice. (2015). Justice data lab reoffending analysis: Women’s centres throughout England. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/427388/womens-centres-report.pdf

- Månsson, S. A., & Hedin, U. C. (1999). Breaking the Matthew Effect – On women leaving prostitution. International Journal of Social Welfare, 8(1), 67–77.

- Najavits, L. M. (2002). Seeking safety: A manual for PTSD and substance abuse. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Page, A., & Rice, B. (2011). Counting the cost: The financial impact of supporting women with multiple needs in the criminal justice system – Findings from Revolving Doors Agency’s women-specific Financial Analysis Model. Retrieved from http://www.revolving-doors.org.uk/file/1793/download?token=_uhAj6qr

- Roe-Sepowitz, D., Gallagher, J., Hickle, K. E., Loubert, M. P., & Tutelman, J. (2014). Project ROSE: An arrest alternative for victims of sex trafficking and prostitution. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 53(1), 57–74.

- Tate, K. (2015). Losing my voice: A study of the barriers and facilitators to disclosure for sex-working women in residential drug treatment. Retrieved from http://www.thegriffinssociety.org/system/files/papers/fullreport/griffins_research_paper_2015-02_final.pdf

- Tompkins, C. N. E., & Neale, J. (2016). Delivering trauma-informed treatment in a women-only residential rehabilitation service: Qualitative study. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 25(1), 47–55.

- Ward, H., Day, S., & Weber, J. (1999). Risky business: Health and safety in the sex industry over a nine-year period. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 75(5), 340–3.

About Me

John Trolan is the chief executive of The Nelson Trust, a multiple-award-winning organization delivering residential treatment services for individuals with drug and alcohol dependencies and community services for women with multiple vulnerabilities. He has written numerous articles and presented at national and international conferences on the work of the Trust, which is based in the Cotswolds, UK.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.