LOADING

Share

It is widely known that a positive therapeutic alliance is a critical and necessary component of successful treatment outcomes for those who seek therapy. The therapeutic alliance is often cited as the most important aspect of a client’s substance abuse treatment and subsequent recovery. This article seeks to discover if a positive therapeutic alliance is also helpful in the treatment of substance use disorders and how substance abuse treatment providers can develop positive therapeutic alliances with their clients. In the first section we will explore the current standard treatment modalities for substance use disorders. We will then define the therapeutic alliance in more detail and discuss various aspects of a therapeutic alliance. Next we will discuss the efficacy of the therapeutic alliance in substance abuse treatment and the counselor characteristics and treatment techniques that can assist in developing a positive therapeutic alliance. This article will then explore how development and maintenance of a positive therapeutic alliance can be taught to substance abuse counselors, looking at specific training programs and the use of clinical supervision. We will conclude with a few recommendations for best practice training methods on therapeutic alliance-building.

Usual Therapeutic Practices in the United States

Before discussing therapeutic alliance in the United States, one must understand the usual therapeutic practices within addiction treatment. According to Fisher and Harrison (2012), motivational interviewing (MI) is a therapeutic modality in which a counselor can stimulate a person who is addicted to alcohol and other drugs to seek help. This client-centered therapy has four key factors: “Express empathy, develop discrepancy, roll with resistance, and support self-efficacy” (Fisher & Harrison, 2012, pp. 125). Therefore, a therapist would utilize these skills to influence self-change within the client. Again, this type of therapy is client-centered—Fisher and Harrison state “the main role that the therapist plays is to elicit a client’s ambivalence about changing, thoroughly explore this ambivalence, and facilitate the resolution of the ambivalence” (2012, pp. 125).

However this is just one type of therapeutic practice. Fisher and Harrison (2012) also mention some brief interventions that are often used as common therapeutic practices within agencies: “The procedures can range from a five-minute explanation of the harm of AOD by a health care provider, to a mental health counselor encouraging a client to see if he or she can stop drinking on his or her own, to more structured programs” (pp. 132). Therefore, this type of therapeutic practice is varied, though this might be seen as a practice that is used most with clients.

Another therapeutic modality used often with clients who are addicted to alcohol and other drugs (AOD) is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), a highly functional modality that can be used to examine a client’s AOD use (Carroll, 1998). Through this therapy the counselor is able to individualize a client’s treatment by giving the client tools to identify and recognize cravings and then process where these thoughts originate. Thus, a client can practice skills such as stopping negative thoughts and replacing them with positive and encouraging thoughts (Carroll, 1998). One might think that CBT is a therapy that involves too many confusing factors; however CBT is a modality that can be precise and very individualized in aiding a client with their AOD addiction.

Therapeutic Alliance

The term “therapeutic alliance,” or “therapeutic relationship” as some may call it, refers to the actual trust between the counselor or therapist and the client (Cabaniss, 2012). This trust allows the counselor to work effectively with the client. Specifically for AOD users, therapeutic alliance can aid in the relationship that one has with their counselor, therefore helping them with their recovery. Cabaniss (2012) describes the key part of a therapeutic relationship between a counselor and a client as the empathy that the counselor provides. For example, letting the client know how difficult it may be to go through the events that have led them to the agency. What may seem like a simple technique such as empathy can go a long way when establishing trust and therapeutic alliance with a client.

A study about deconstructing the therapeutic alliance describes what clients and counselors identified as being primary aspects to a functional relationship: “Clients must experience from their therapists in order to have a good therapeutic relationship: (a) acceptance, (b) trust, and (c) feeling understood” (Krause, Altimir, & Horvath, 2011, pp. 271). This data sheds light upon how important a client must feel for a therapeutic alliance to be formed. A client must be shown that the counselor genuinely cares and is able to empathize with the client for a relationship to be established (Krause et al., 2011).

With that said, the therapeutic alliance does change over the course of the therapy sessions. In the study by Krause, Altimir, and Horvath (2011) the counselors describe that a key point within their therapeutic relationship was when their clients disclosed personal information. This may seem like a simple act, but it does denote trust to the counselor. Another key factor that clients in the study pointed out was if the session invoked strong emotions for them. Having strong emotions during the session made the client evaluate the sessions more positively (Krause et al., 2011). The evolution of the therapeutic relationship can be subtle yet helpful for the client in their recovery.

In another study conducted about therapeutic alliance and mindfulness intervention trainings for smokers, it was shown that the therapeutic relationship aided in the mindfulness training. According to Goldberg, Davis, and Hoyt, “this study provides evidence to suggest that therapeutic alliance plays a role in particular positive outcomes associated with a mindfulness-based intervention and suggests that researchers and clinicians may benefit from considering therapeutic alliance as an unexplored aspect of mindfulness treatments” (2013, pp. 946). Although the therapeutic alliance did not help with the smokers quitting, it did assist with the mindfulness skills training and interventions (Goldberg et al., 2013, pp. 946). Thus, this study depicts that a therapeutic relationship can help promote a modality’s intervention, such as mindfulness. More so, this study shows that having a therapeutic alliance with a client is a best practice especially when delivering an intervention and skills training.

Efficacy

Meier, Barrowclough, and Donmall (2005) conducted a comprehensive review of studies on the effect of the therapeutic alliance on addiction treatment. This review evaluated the impact of the therapeutic relationship on retention, engagement, and treatment outcomes for substance using clients. Although Meier and colleagues (2005) attempted to draw firm conclusions from this comprehensive analysis, methodological variance made it difficult to identify solid findings from the studies regarding the role of the therapeutic alliance.

The authors did find that successful engagement of clients in the drug treatment program predicted positive treatment outcomes (Meier et al., 2005). Counselors who were able to engage their clients early on in the treatment process consistently had better long-term recovery outcomes. Additionally, certain counselor characteristics were found to be strong predictors of engagement in treatment differentially among men and women. For men, positive ratings of the counselor in terms of helpfulness were related to engagement, and for women, the counselor’s caring was associated with treatment engagement (Meier et al., 2005). These findings may be important factors for counselors to take into consideration when they are trying to engage clients in treatment.

In regards to retention in treatment, Meier and colleagues (2005) found moderate effect sizes between positive therapeutic relationships and long-term retention in treatment. The studies that were reviewed analyzed the therapeutic alliance only at certain points in treatment, usually in the early stages, which makes this finding difficult to confirm. It appears that an early positive therapeutic alliance was significant in determining retention, but the authors were unable to make conclusions evaluating the alliance over time (Meier et al., 2005).

Unfortunately, this comprehensive analysis could not determine a consistent finding regarding the effect of the therapeutic alliance on treatment outcomes and recovery. Of the multiple studies reviewed, Meier et al. (2005) found inconsistent and contradictory results. However, the study did find that an early favorable therapeutic alliance was effective in engaging and retaining clients in addiction treatment. A positive therapeutic alliance was also found to predict positive early recovery outcomes, but findings were inconsistent regarding long-term recovery.

Teaching Therapeutic Alliance-Building

Given the evidence suggesting that a positive therapeutic alliance is a critical component of successful drug addiction treatment outcomes, it is worthwhile to examine how a positive therapeutic alliance can be taught to counselors. In this section we will also examine specific counselor behaviors and treatment techniques that contribute to a positive therapeutic alliance.

In a preliminary study designed to evaluate the impact of alliance-fostering therapy on the therapeutic alliance, Crits-Christoph and colleagues (2006) found that specific techniques of alliance-fostering therapy could lead to improvements in the therapeutic alliance. This study trained five therapists in alliance-fostering therapy, which is based on Bordin’s (1979) conceptualization of the therapeutic alliance, and assessed for changes in client evaluation of the therapeutic alliance. Bordin’s definition of the therapeutic alliance is “the emotional bond between patient and therapist, agreement on tasks, and agreement on goals” (Crits-Cristoph et al., 2006, pp. 268). While this study looked specifically at therapists who were treating clients with major depressive disorder, the alliance-building treatment approach could also be utilized with clients seeking substance abuse treatment.

While the researchers acknowledged that existing studies of the therapeutic alliance have usually focused on client characteristics that are predictive of alliance-building, this study sought to focus on counselor characteristics. Earlier studies “conclude that when the therapist conveys a sense of being trustworthy, affirming, flexible, interested, alert, relaxed, confident, respectful, and empathic and is more experienced and communicates clearly, a more positive alliance is present” (Crits-Cristoph et al., 2006, pp. 269). Alliance-fostering therapy seeks to instill these qualities in counselors as well as enhance specific therapeutic techniques such as agreement on treatment goals, regular review of goals and tasks, as well as enhanced quality of the patient-therapist bond (Crits-Cristoph et al., 2006). The counselors were also instructed on how to establish a collaborative approach, communicative contact, and mutual affirmation between the counselor and client for therapy.

The therapists in this study were trained in alliance-fostering therapy with an initial workshop and intensive supervision throughout the study. The supervisor was a clinician with extensive practical and training experience. The supervisor reviewed the sessions with the therapists and provided suggestions for future interventions utilizing alliance-fostering therapy techniques. Assessment of the therapeutic alliance was conducted using the California Psychotherapy Alliance Scale-patient version (CALPAS-P) and the Helping Alliance Questionnaire (HAq-II) (Crits-Cristoph et al., 2006).

Crits-Cristoph et al. (2006) found that alliance-fostering therapy was successful for some counselors in improving their alliance-building techniques. While the results of this study were not statistically significant, there was some evidence that training programs, such as alliance-fostering therapy, may be helpful in improving the therapeutic alliance. The results were inconsistent among the therapists in the study however, which suggests that some counselors may be more receptive to alliance-building training.

Another study by Duff and Bedi (2010) examined particular counselor behaviors and characteristics that were predictive of a positive therapeutic alliance as evaluated by clients. Again, these clients were not specifically in treatment for substance use, but the results of the study could be generalizable to most populations involved in a therapeutic relationship. Duff and Bedi’s (2010) study looked at fifteen counselor behaviors that were identified in their previous research and asked clients to rate the importance of each in the development and maintenance of a positive therapeutic alliance. The clients in this study used the Therapeutic Alliance Critical Incidents Questionnaire (TACIQ) and the Working Alliance Inventory, Short Form, Revised (WAI-sr) to measure their perspective of the strength of the therapeutic alliance.

The study found a positive relationship between the frequency of the previously identified counselor behaviors and the strength of the positive therapeutic alliance. The fifteen characteristics can be divided into four main categories: behaviors that exhibited validation, nonverbal attending skills, behaviors not correlated with alliance, and behaviors that portray positive regard for the client.

Duff and Bedi (2010) found the following in their study on positive counselor behaviors:

- The behaviors that can be characterized as validation include “asking questions, making encouraging comments, identifying and reflecting back the client’s feelings, making positive comments about the clients, and validating the client’s experience” (p. 99)

- Physical attending skills such as “making eye contact, greeting the client with a smile, referring to details discussed in previous sessions, being honest, sitting still without fidgeting, and facing the client” were identified as positively enhancing the therapeutic alliance (p. 101).

- The four behaviors that were not found to influence the therapeutic alliance were “telling the client about similar personal experiences, letting the client decide what to talk about, providing verbal prompts, and keeping administration outside of session time” (p. 101).

- The behaviors that portrayed a sense of positive regard towards the client were identified as “making encouraging comments, making positive comments about the client, and greeting the client with a smile” (p. 101).

The aforementioned client-identified behaviors should be encouraged in counselors in order to develop and maintain a positive therapeutic alliance. Of course cultural differences should always be taken into consideration when a counselor is meeting with a client. Furthermore, counselors should be engaging in these behaviors in an authentic and genuine way and not think of them as a script to conduct their therapeutic sessions by.

Skill Development

One way a counselor can develop their therapeutic relationship skill development is through clinical supervision. Clinical supervision is when a counselor receives knowledge about skills—which in this case pertains to AOD treatment—from their supervisor (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2009). This clinical supervision becomes highly important especially within the substance abuse field because it assists with the promotion of counselor’s skills as well as encourages continuing education amongst staff (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2009). Hence, if the counselor feels confident in their skills and is supported by his or her supervisor, then the therapeutic alliance will also be strong, which trickles down to the delivery of services.

To break it down even further, the supervisor plays four main roles in the relationship with the counselor. First the supervisor takes on the role of a teacher; in this role he or she assists in providing knowledge of counseling skills and promotes growth on a professional level (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2009). Secondly, the supervisor functions as a consultant. In this function, the supervisor incorporates the monitoring of job performance as well as assesses the counselors (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2009). The supervisor’s third role is as a coach to the counselor. In this role, the supervisor provides “morale building, assesses strengths and needs, suggests varying clinical approaches, model, and prevents burnout” (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2009). Lastly, the supervisor provides the role of a mentor or role model—a significant role because the supervisor teaches the counselor overall skills and knowledge through modeling of professional development (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2009). Again, having a supervisor within the substance abuse field who is able to support and guide his or her counselors is highly important. Through clinical supervision, a counselor can assess their skills and therapeutic alliance with their clients. Therefore, clinical supervision with a supervisor who exudes the four aspects as stated above is extremely important when developing a therapeutic relationship with a client.

Best Practice Training Methods

Muran and Barber’s (2010) text provides an excellent overview of evidence-based approaches to initiating and enhancing a positive therapeutic alliance. While it would be out of the scope of this article to review the text fully, the authors list five recommendations for training of staff in therapeutic alliance-building. These recommendations are not specifically for training of addiction counselors and are aimed more towards general therapists, but are nonetheless useful in instruction on how to train clinical staff in therapeutic alliance skills.

- The first recommendation is that counselors become familiar with how to repair ruptures in the therapeutic alliance. There are several manuals on how to do so and the Muran and Barber text provides a list of them.

- The second recommendation encourages therapists to review their alliance with their clients regularly by checking in with them during therapy and asking for feedback or concerns.

- The authors also recommend that counselors regularly assess their alliances in a formal manner with standardized evaluations, such as those mentioned previously in this paper (HAq-II, WAI-sr, etc).

- The fourth recommendation is to utilize role plays, case studies, videotaped sessions, and other didactic methods to train staff in alliance-building.

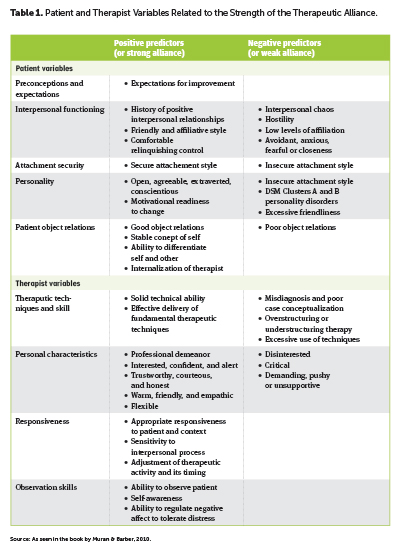

- The final recommendation is that staff should be trained to be “self-aware, interpersonally sensitive, and able to regulate their affect to best effect” (Muran & Barber, 2010). Other patient and therapist characteristics that are predictive of the therapeutic alliance can be found in Table A.

Conclusion

This article sought to answer the following question: How can treatment programs and providers develop positive therapeutic alliances with clients? Our research indicated that a positive therapeutic alliance, especially early on in the therapeutic relationship, can have a beneficial effect on treatment retention and recovery outcomes. While it cannot be said for certain that a positive therapeutic alliance will produce a positive treatment outcome, there is no evidence that a positive therapeutic alliance could or would have a detrimental effect on treatment. Although it is usually true in the substance abuse field that a client must be willing and committed to recovery, a positive therapeutic alliance with their counselor may increase their trust, self-efficacy, and ultimately their recovery. Substance abuse counselors should demonstrate empathy, validation, positive regard for the client, and flexibility in order to build a positive therapeutic alliance with their clients. Additionally, counselors should utilize clinical supervision in order to enhance their treatment modality delivery and to regulate their personal affect for the benefit of their clients. Regular review of the treatment plan and agreement on treatment goals is also crucial to a positive therapeutic alliance. Various training programs for staff professional development in regards to the therapeutic alliance are available and may be of use to some counselors, especially new counselors or those who were trained in more confrontational methods. While the provision of substance use treatment may be difficult, it appears that the development and maintenance of a positive therapeutic alliance will assist counselors in more efficiently and effectively serving their clients.

Acknowledgements: This work was supported by the Community-Academic Partnership on Addiction (CAPA).

References

Bordin, E. S. (1979). The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 16(3), 252–60.

Cabaniss, D. L. (2012). The therapeutic alliance: The essential ingredient for psychotherapy. Huffington Post. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/deborah-l-cabaniss-md/therapeutic-alliance_b_1554007.html

Carroll. K. M., (1998). A cognitive-behavioral approach: Treating cocaine addiction. Retrieved from http://archives.drugabuse.gov/TXManuals/CBT/CBT1.html

Crits-Christoph, P., Connolly Gibbons, M., Crits-Christoph, K., Narducci, J., Schamberger, M., & Gallop, R. (2006). Can therapists be trained to improve their alliances? A preliminary study of alliance-fostering psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 16(3), 268–81.

Duff, C. T., & Bedi, R. P. (2010). Counsellor behaviours that predict therapeutic alliance: From the client’s perspective. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 23(1), 91–110.

Fisher, G. L., & Harrison, T. C. (2012). Substance abuse: information for school counselors, social workers, therapists, and counselors (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Goldberg, S. B., Davis, J. M., & Hoyt, W. T. (2013). The role of therapeutic alliance in mindfulness interventions: Therapeutic alliance in mindfulness training for smokers. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(9), 936–50.

Krause, M., Altimir, C., & Horvath, A. (2011). Deconstructing the therapeutic alliance: Reflections on the underlying dimensions of the concept. Clinica Y Salud, 22(3), 267–83.

Meier, P. S., Barrowclough, C., & Donmall, M. C. (2005). The role of the therapeutic alliance in the treatment of substance misuse: a critical review of the literature. Addiction, 100(3), 304–16.

Muran, C. J., & Barber, J. P. (2010). The therapeutic alliance: An evidence-based guide to practice. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

US Department of Health and Human Services. (2009). Clinical supervision and professional development of the substance abuse counselor: A treatment improvement protocol TIP 52. Retrieved from http://www.readytotest.com/PDFs/TIP52.pdf

Suggestions for Further Reading

Ferreira, P. H., Ferreira, M. L., Maher, C. G., Refshauge, K. M., Latimer, J., & Adams, R. D. (2013). The therapeutic alliance between clinicians and patients predicts outcome in chronic low back pain. Physical Therapy, 93(4), 470–8.

Hartmann, A., Orlinsky, D., & Zeeck, A. (2011). The structure of intersession experience in psychotherapy and its relation to the therapeutic alliance. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(10), 1044–63.

Nissen-Lie, H. A., Havik, O. E., Høglend, P. A., Monsen, J. T., & Rønnestad, M. H. (2013). The contribution of the quality of therapists’ personal lives to the development of the working alliance. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(4), 483–95.

Richardson, D. F., Adamson, S. J., & Deering, D. E. A. (2012). The role of therapeutic alliance in treatment for people with mild to moderate alcohol dependence. International Journal of Mental Health & Addiction, 10(5), 597–606.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.