Share

Substance use, both alcohol and drug related, impacts communities differently. This is especially true for rural communities throughout America (Dew, Elifson, & Dozier, 2007). Rural communities experience especially high rates of both alcohol and methamphetamine use (Gfroerer, Larson, & Colliver, 2007). This research aims to shed more light on some of the reasons for this and possible early prevention and intervention programs to address these areas of concern.

Background

Twenty percent of the US population live in rural places (Pruitt, 2009). This represents one in every five Americans and brings special challenges to living—access to adequate health care, namely mental health and substance abuse care, is chief among them. Incentivizing health care systems (e.g., hospitals, clinics, labs) and providers (e.g., doctors, nurses, counselors) to operate in rural America is challenging in itself. These are not new challenges, rather they are now more widely discussed due to substance use epidemics that have damaged rural communities greatly. Stories circulate in popular media about the devastating effects of opioid and methamphetamine use across the country.

Oftentimes, when substance use is discussed in many communities, professionals have a tendency to tell consumers what they need. More work is needed to solicit input from communities, particularly those in rural areas, regarding their unique substance use challenges and early prevention/intervention needs. This project hopes to capture some of these challenges and the appropriate early prevention and intervention techniques.

Substance use prevention and intervention programs and/or services should be implemented early in adolescence. Some research identifies over half of those seeking substance abuse treatment having an onset of drug use experimentation before the age of fifteen (Jiloha, 2017). Again, this is not a new finding. Researchers and practitioners need to identify programs and services that meet the threshold of reducing substance use among youth. One such prevention/intervention technique that has received empirical support is the mentorship program (Hanlon, Bateman, Simon, O’Grady, & Carswell, 2002). Mentorship programs can provide structure and stability where it may be either lacking or absent for youth. They may also offer a kind of support which youth may not have access to elsewhere. Mentorship programs provide a type of guidance which is not always available for youth.

The Study

In December of 2018, members of the Substance Abuse Subcommittee of the Community Justice Collaborating Council (CJCC) of St. Croix County, Wisconsin came together to discuss some of the substance use issues facing the community. Out of this meeting was born a task force to develop a survey aimed at collecting self-report information on substance use, mental health, criminal justice involvement, family history, social/behavioral history, and community connections challenges.

Survey development went through a rigorous process. Each of the survey items are grounded in theory and have been explored in other studies. After the items were developed, the researchers presented the survey to the Substance Abuse Subcommittee and received feedback for revisions. The final step in this process was a formal presentation to the entire CJCC committee in March 2019 and approval of the project. Because of the affiliation of one researcher, the project was required to receive approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Wisconsin – River Falls (UWRF) before data collection would begin. This condition was satisfied in August 2019.

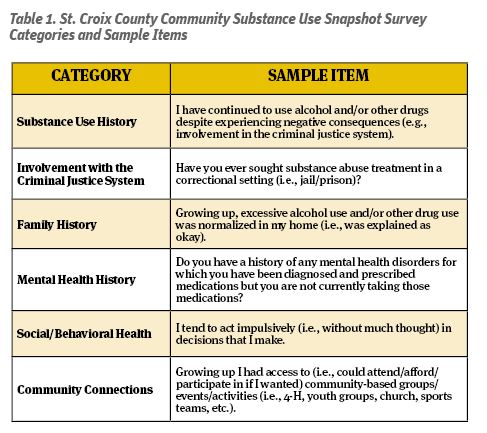

The St. Croix County Community Substance Use Snapshot Survey is comprised of fifty-nine questions, broken down into six categories (please see Table 1 for a breakdown of the six categories and a sample item from each). The intent of constructing the survey in this manner was to capture as much information surrounding substance use as possible. We believe this goal was accomplished.

Data Collection

Beginning in September 2019, the researchers teamed up with two members of the recovery community in St. Croix County to distribute the survey to willing participants. This was a valuable approach for several reasons. First, participants from the recovery community are in a unique position to comment specifically on substance use history and dependency. Second, starting with this population would hopefully allow for a snowball sampling methodology where willing participants may introduce the researchers to others in the recovery community. Some of this was realized, while some was not.

Data collection in the recovery community took place through December 2019, at which time the researchers decided to take the project in a new direction. Beginning in January 2020, researchers solicited participation from individuals involved in the treatment court program in St. Croix County, Wisconsin. Data collection with this population has been impactful and remains ongoing.

The Treatment Court in St. Croix County is similar to the many “drug courts” throughout the country that became popular in the late 1980s starting in Miami-Dade County, Florida (Goldkamp, 1994). Individuals have to apply for admission into the intensive program, which is done through a referral process. Some of the criteria for admission include being at least seventeen years of age or older (i.e., an adult) and a resident of the county; having a pending drug- or alcohol-related offense (mostly felonies, but misdemeanors are accepted occasionally) and no other pending felony charges; and not being designated as a violent offender by Wisconsin State Statute (St. Croix County Government Center, n.d.). Status hearings are held every Wednesday as the therapeutic team meets to discuss each individual case. This team includes the individual, judge, treatment court coordinator, prosecutor, and other treatment staff. Individuals move through phases and “phase up” when certain therapeutic and legal goals have been accomplished. Many of the individuals in this program are at risk for failing to complete “traditional” methods of legal intervention (e.g., probation) due to substance use issues and are instead diverted to the Treatment Court for additional supervision.

Results/Discussion

As of February 2020, twenty-four individuals had completed the St. Croix County Community Substance Use Snapshot Survey (n=24). While this is a small sample size, the results yield some important and worthwhile findings. What follows below are some of the demographic results.

More work is needed to solicit input from communities, particularly those in rural areas, regarding their unique substance use challenges and early prevention/intervention needs.

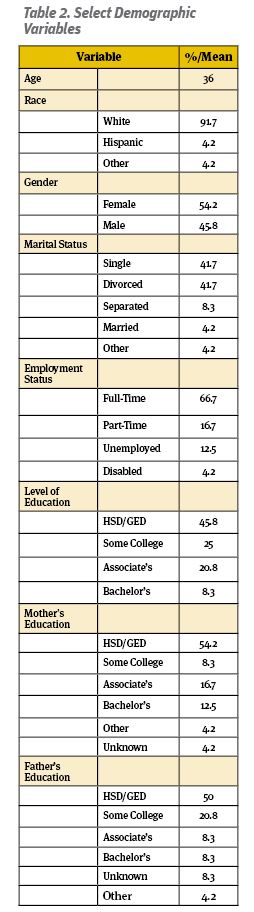

The mean age of the respondents was thirty-six (see Table 2 for all demographic variables). Approximately 92 percent of the respondents identified as white, close to the roughly 96 percent of the county’s general population who identify with this racial group (US Census Bureau, 2016). Over half (54.2 percent) of the respondents identified as female, possibly a note to women in the recovery community fulfilling the traditional spot of “help-seeking behavior” (Windle, Miller-Tutzauer, Barnes, & Wilte, 1991)—that is, the gender stereotype that women are more likely to seek help for problematic behavior than men. Only 4.2 percent of the sample were married, with much larger percentages (41.7 percent) of being single and divorced, which may be a reflection of substance abuse history damaging past relationships. Interestingly, 66.7 percent of the sample were employed full-time, showing that many of the respondents may be able to navigate both substance use and gainful employment. This goes against many of the anecdotal thoughts behind alcoholism and drug abuse that these individuals are unable to hold a legitimate job. Finally, 45.8 percent of respondents claimed a high level of education as high school diploma/GED. This is increasingly interesting as these same individuals report that their parents (54.2 percent of mothers, 50 percent of fathers) obtained that same highest level of education. This also shows that many of the respondents are undereducated, at least by St. Croix County standards, as only 25.9 percent of the county’s overall population reports a high school diploma/GED as their highest level of education received. That is, greater percentages of the county’s overall population report higher levels of educational attainment in categories such as having a bachelor’s degree, for example.

A few other notes regarding educational attainment. If parents are only educated at a certain level, they may be unaware of how to effectively communicate about drug and alcohol use to their children. Additionally, if some of the intervention and prevention services are happening later in academic life (i.e., college and university programs against problem drinking and drug use), some of our respondents are not getting these messages. It may also be that if education is not a priority in some of these households, any messages about continued learning—let alone about substance use—are not taking place.

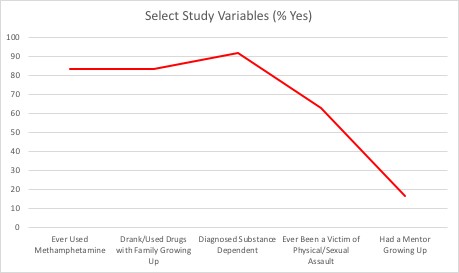

There are several noteworthy findings from select study variables. Figure 1 displays trends for a few items of interest from the study. The first is that 83.3 percent of participants reported ever using methamphetamine. While this is of particular interest to a county experiencing challenges with methamphetamine use, this is still a high number. Additionally, it is important to consider that this survey was given largely to a former substance-using population (i.e., people in the recovery community and in treatment court) and that reason alone may be responsible for the high number.

Similar to methamphetamine use, 83.3 percent of respondents reported drinking before the age of twenty-one and/or using drugs with family members growing up. This certainly points to a trend in drug and alcohol use being normalized. It may also be that respondents were socialized to accept problem alcohol and drug use. Regardless, this speaks to the need for early prevention, and in many cases it appears, early intervention.

Not so surprisingly, approximately 92 percent of the sample reported being diagnosed as substance dependent. Again, sampling from a recovery community and treatment court will likely yield these types of results. In a bit of a departure from substance use, 62.5 percent of participants reported ever being the victim of physical or sexual assault—this is a shockingly high number. While this may not speak directly to substance use, it definitely does allude to what may be referred to as “systemic crimes.” That is, it is not just that there is only a direct relationship between drugs and/or alcohol and some other unwanted behavior (i.e., crime). Instead, both physical and sexual victimization may be taking place in these situations as well. Finally, on a policy-related note, only 16.7 percent of participants reported having a mentor while growing up. This will be discussed in further detail later in this article.

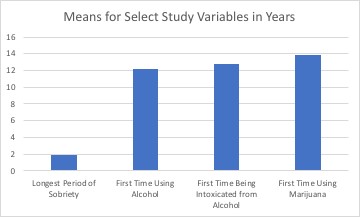

Figure 2 shows age of onset for select drug and alcohol use. Participants reported a mean age for first time consuming alcohol at 12.13 years, which would put many respondents in either the sixth or seventh grade (i.e., middle school). Following this, participants reported their first time being intoxicated from alcohol use at 12.83 years. This makes sense, as participants may experiment with alcohol use initially and drink to intoxication soon after. Regarding drug use, participants reported their first time using marijuana at 13.87 years. It is likely that many individuals are experimenting with marijuana use before even entering high school. Finally, and positively, the mean number of years for sobriety for the respondents was 1.95 years. This has important implications for policy.

Conclusions/Policy Implications

Because respondents report on average nearly two years as their longest period of sobriety, there should be enthusiasm surrounding substance use work in communities. Not only are individuals wanting to remain sober, but they are doing so without the assistance of new programming. These are encouraging results and point to the need for more effective programs and services to increase this number.

As only 16.7 percent of participants in the study reported having access to a mentor while growing up, this should be the main focus of practitioners. This is especially important given that few prevention and intervention techniques against substance use are being taught at home, highlighted by the roughly 83 percent of participants reporting normalization of drug use and/or problem drinking at home while growing up.

Mentorship programs may be difficult to implement for a number of reasons. Firstly, agencies do not always have the proper funding for mentorship programs. Additionally, these are often among the first programs cut during budget crises (Dombrowski, Crawford, Khan, & Tyler, 2016). Local practitioners should apply for grants and other funding opportunities to support these types of programs. Secondly, developing a pool of appropriate mentors may be challenging. These programs may require large time investments that not everyone is willing to make. Policy experts will need to find ways to incentivize individuals in communities to volunteer their time. Finally, policy analysts should engage in constant evaluation of their mentorship programs to ensure they are meeting the needs of the communities they serve. Too often, underperforming programs are allowed to continue when they are both ineffective and not accomplishing what they set out to (Dombrowski et al., 2016). We should not continue to throw good money at bad programs.

Mentorship programs can help to fill a void in someone’s life where there is either a gap or complete absence of support. One of the more important aspects of mentorship program implementation is they take place early in life. Our research identifies onset of alcohol use at age twelve and marijuana at age thirteen (see Figure 2). Thus, practitioners should target possible at-risk youth no later than age ten. It is not enough to meet youth right when substance use onset is taking place; rather, this should be done years in advance so bonds can be formed between mentor and mentee. This will also allow time for building skills such as coping strategies and establishing other prosocial outlets.

Limitations/Future Research

As with all research, this study is not perfect. The first limitation has to do with the current sample size. Twenty-four respondents is hardly a robust sample size, but it does provide room for a lot of growth. As of this writing, seven more treatment court participants completed the St. Croix County Community Substance Use Snapshot Survey, though data were not available in time for analysis in this article. Researchers are in the process of applying for external funding opportunities, which will allow for greater outreach in data-collection efforts.

The second limitation is that the current results are biased by the sampling methodology. That is, by engaging in a form of convenience sampling in the recovery community and treatment court, the current results will obviously be skewed towards greater reports of substance use history and dependency. It will be important for future research to sample from different groups which accurately represent the demographics of the community.

The design of the current study is cross-sectional in nature in that it collects responses from multiple respondents across one time point. Future research would benefit from a longitudinal design, where respondents participate in the survey across multiple time points (e.g., months, years, etc.). This would allow for drawing casual inferences and time-ordering, which cannot be done in its current format.

References

- Dew, B., Elifson, K., & Dozier, M. (2007). Social and environmental factors and their influence on drug use vulnerability and resiliency in rural populations. The Journal of Rural Health, 23(Suppl. 1), 16–21.

- Dombrowski, K., Crawford, D., Khan, B., & Tyler, K. (2016). Current rural drug use in the US Midwest. Journal of Drug Abuse, 2(3), 22.

- Gfroerer, J. C., Larson, S. L., & Colliver, J. D. (2007). Drug use patterns and trends in rural communities. The Journal of Rural Health, 23(Suppl. 1), 10–5.

- Goldkamp, J. S. (1994). Justice and treatment innovation: The drug court movement: A working paper of the first National Drug Court Conference, December 1993. Retrieved from https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/Digitization/149260NCJRS.pdf

- Hanlon, T. E., Bateman, R. W., Simon, B. D., O’Grady, K. E., & Carswell, S. B. (2002). An early community-based intervention for the prevention of substance abuse and other delinquent behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 31(6), 459–71.

- Jiloha, R. C. (2017). Prevention, early intervention, and harm reduction of substance use in adolescents. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 59(1), 111–8.

- Pruitt, L. R. (2009). The forgotten fifth: Rural youth and substance abuse. Stanford Law & Policy Review, 20(2), 359–404.

- St. Croix County Government Center. (n.d.). Treatment court. Retrieved from https://www.sccwi.gov/308/Treatment-Court

- US Census Bureau. (2016). ACS demographic and housing estimates. Retrieved from https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?d=ACS%205-Year%20Estimates%20Data%20Profiles&tid=ACSDP5Y2016.DP05

- Windle, M., Miller-Tutzauer, C., Barnes, G. M., & Welte, J. (1991). Adolescent perceptions of help-seeking resources for substance abuse. Child Development, 62(1), 179–89.

About Me

Phillip M. Galli, PhD, is a visiting assistant professor in the Department of Sociology, Criminology, and Anthropology at the University of Wisconsin – River Falls. His research interests include social support of justice-involved populations and substance use prevention/intervention strategies in communities. Galli’s dissertation work looks at the role of social support prior to incarceration on social support while in prison. Prior to working in academics, he was a probation/parole officer in the states of Missouri, Ohio, and Illinois for over eight years.

Kimberly Kitzberger joined St. Croix County as the juvenile treatment court coordinator in March of 2014 and was promoted to treatment court coordinator of the adult program in May of 2015. With over ten years of experience in the clinical treatment of substance use disorders, Kim brings a wealth of knowledge and compassion to her role as coordinator, case manager, and advocate.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.