LOADING

Share

Chronic inter- and intrapersonal dysfunction takes many forms. Interpersonal dysfunction can include conflicts in intimate and social relationships (attachment issues, unsatisfying or problematic social role patterns), maladaptive styles of interpersonal responding (passive, aggressive, avoidant), social isolation, and/or perceived lack of or unhealthy social support systems. Chronic intrapersonal dysfunction comprises problems such as enduring, negative perceptions of one’s environment and/or self, low self-esteem, long-standing clinical symptoms (depression, anxiety) and maladaptive mood states (e.g., anger, fatigue, etc.). These chronic patterns of inter- and intrapersonal problems often form the basis of Axis I and/or Axis II disorders, that are typically addressed in weekly or more psychotherapy sessions over months or years in therapy.

To address these chronic problems, the Breakthrough program at Caron Treatment Centers was created in 2009 by Ann Smith, MS, LPC, LMFT. In working with family members of individuals addicted to substances, Smith found common recurring themes with these families related to chronic dysfunction. In 1984, she created the intensive adult children of alcoholics program at Caron to address issues thought to be associated with growing up in an alcoholic family, including codependency (Smith, 1988). Since then, Smith and colleagues have expanded and updated the program’s scope to address the beliefs and behavioral strategies people develop in response to the chronic stress of growing up in a “painful family” with chronic emotional dysregulation, addictions, negativity, and/or abuse (Smith, 2013). The program thus evolved into its current form, a five-day residential program of intensive experiential group therapy for individuals with chronic problematic relationships and other dysfunctional life patterns. This is one of the first such residential programs in the country.

The program content is rooted in attachment theory (e.g., Obegi & Berant, 2010) and focuses on survival strategies that individuals develop early in life to cope with growing up in a stressful or painful family. Dysfunctional survival strategies—such as an external locus of control, repressed feelings, comfort with crisis, and difficulty regulating emotions in close relationships—are consistent with anxious, avoidant, or fearful-avoidant or disorganized attachment styles. These problematic survival strategies tend to persist throughout the lifespan, often resulting in frustrating and treatment-resistant inter- and intrapersonal problems.

Defining and Evaluating Targets of Personal Growth

The targets of personal growth can be understood in a framework of contemporary interpersonal and attachment theory (Gallo, Smith, & Ruiz, 2003; Gurtman, 1996; Stuart & Robertson, 2003) and can be subsumed under a validated, research-driven model—early maladaptive schemas (Young, Rygh, Weinberger, & Beck, 2008)—which focuses on enduring negative perceptions of self and environment that are developed early in life, and are associated with mood, anxiety, and/or personality disorders in adulthood. That is, survival strategies can be operationalized as early maladaptive schemas. The maladaptive schema model is based on the following five developmental schema domains (Young, Klosko, Weishaar, 2006).

Disconnection and Rejection

Common problems in this domain include abandonment, instability, mistrust, abuse, emotional deprivation, feelings of defectiveness or shame, and social isolation or alienation. This domain is often related to having unmet needs such as security, empathy, and safety in families of origin that might be rejecting, explosive, cold, unpredictable, and/or abusive.

Impaired Autonomy and Performance

Common problems here include dependence, incompetence, vulnerability to harm, enmeshment, and feelings of failure. Problems in this domain are often found in adult children whose parents often undermined their confidence and competence.

Impaired Limits

Common problems in this domain include entitlement and lack of control. These problems are usually associated with deficits in responsibility, ability to form or pursue long-term goals, and respect for others.

Other Directedness

Common problems here include subjugation (i.e., allowing oneself to be controlled by others as a way to seek approval), self-sacrifice, and the popular notion of codependency. People with active other directedness schema tend to focus on the needs of others at the expense of their own in order to feel accepted and loved. People with these problems often grow up in families that offer only conditional love and acceptance.

Overvigilance/Inhibition

Common problems in this domain include emotional inhibition, unrelenting standards, hypercriticalness, pessimism, and self-punitiveness. Problems in this area can be associated with a family of origin characterized by negative affect and perfectionism.

A goal of relational or schema-focused therapy is to weaken and replace these negative schemas with more positive, adaptive cognitions and perceptions of self and environment, thus enhancing self-esteem, optimism, the ability to seek and tolerate supportive relationships, and improved overall psychosocial functioning. Classic schema-focused therapy typically includes stepwise components of assessment and change, over at least sixteen individual therapy sessions (Young et al., 2008). An emphasis is placed on the therapeutic relationship, exploring childhood origins of problems, experiential techniques such as imagery and role playing, active addressing of maladaptive cognitions and behaviors, and overcoming cognitive and behavioral avoidance. The level of affect in the therapy is generally high. Breakthrough can be seen as an intensive five-day alternative or adjunct to such courses of individual schema-focused therapy that utilizes similar approaches to target maladaptive beliefs about self, attachment patterns, and chronically dysfunctional interpersonal behaviors.

Participants

Generally, participants appropriate for intensive experiential group-based work have typically been in long-term individual psychotherapy, possibly for several months or years, to address long-standing relationship difficulties and other life problems. Clients who “plateau”—meaning they stop making consistent progress toward their goals in outpatient therapy, but do not require a higher level of care—might particularly benefit from a referral to an experiential treatment experience. For these clients whose long-standing, treatment resistant problems tend to cluster in the interpersonal realm and/or are driven by maladaptive schema, a group-based experiential approach might be especially helpful. While changes to early maladaptive schemas via discussions in the context of individual therapy may lack the follow-through by the client in his or her everyday life, experiential group workshops that utilize an immersion format where participants spend twenty-four hours a day with their group members are designed to activate these maladaptive schemas and to process them in real time. This allows the participant to see immediately the effect of the schemas in his or her life. The ability to recreate through family sculpture from the client’s viewpoint, for instance, provides a visible representation of the family dynamics that often led to the adaption of the particular schemas involved. On the other hand, intensive, group-based experiential work would be contraindicated for patients with active substance use disorders, and/or unstablized Axis I or II disorders that require a higher level of care.

All activities are done in a group context which allows clients to receive group support while experiencing and providing empathy. At the same time, clients are encouraged to develop and practice healthier ways of relating and managing emotions in the moment.

Thus, intense experiential work is targeted to accelerate therapeutic work on important issues such as changing long-standing dysfunctional relational and attachment patterns, enhancing self-esteem, decreasing guilt and shame, addressing residual difficulties from childhood, and changing long-standing and underlying maladaptive beliefs about self. The successful client, upon return to individual therapy, has a better understanding of what has created the “stuck points” in his or her life.

Program

Through decades of experience in the five-day model several essential elements have emerged.

- A peer group in a contained supportive environment makes it possible for participants to risk in ways that they never have before. There are no “exits” for them to retreat to and they tend to work things out with the group rather than escape.

- Thorough screening for appropriateness creates group cohesion and trust and prevents the break down of trust and safety in the group.

- Use of language of normalization to reframe clients’ ineffective patterns along with a lack of negative patterns reduces shame and increases their confidence in their own ability to change and grow.

- Cofacilitation in experiential aspects of group, including psychodrama, makes the group feel safer, counteracts transference issues, provides multiple perspectives, and helps therapists to see all group members’ responses when attention is on one client.

Groups during the day are often kept small, no more than ten participants, so that all individuals are engaged. Both groups remain together during the evening. Breakthrough is intense as it is five days in duration. The program views issues from family systems and attachment theory perspectives, and draws on psychodrama, psychoeducation, family sculpture, discussion of chronic patterns as well as current problems, imagery, affect activation, corrective emotional experience, somatic experiencing, and group bonding, to examine how past events and/or parenting impact current interpersonal and coping struggles.

The program starts with an introduction to attachment patterns utilizing lecture, discussion, visualization, and brief experiential activities. This provides a gentle introduction into the more intense emotional work ahead. Action methods are the basis of most group exercises. Specific, therapist-led experiential components include:

- A triad activity to demonstrate each client’s method of handling attachment anxiety

- A group session on managing painful feelings

- Guided imagery

- Letter-writing to parents focusing on early childhood that is read and processed within small groups

- A session on grief and loss

- Two days of individual psychodrama segments

Group exercises are interspersed with lectures and discussions which provides participants down time between the more intense emotional work. Discussions are interactional and generally include eliciting examples from group members. Handouts are provided each day for the evening program to address compulsive behaviors, boundaries, and detachment; validation and affirmation; and guidelines for writing a “letter from one’s future self, to one’s current self.”

At the end of each day program, clients complete written exercises which are then shared in the evening peer group. Monitored by an evening counselor, these self-directed peer sessions provide an opportunity to address important issues and provide a real-time experience of modifying problematic patterns within a healthy support system.

Therapist Experience

Clinical staff for intensive, group-based experiential programs can be therapists with a range of certifications, including licensed professional counselors, certified experiential therapists, licensed marriage and family therapists, psychologists, social workers, and certified addictions counselors. Therapists should be well-versed in group therapy and group dynamics and have a strong understanding of attachment patterns.

Clinicians facilitating experiential group therapy quickly identify the importance of doing their own therapeutic work. Experiential therapy is a powerful lens through which to view behavioral and relational patterns, as these patterns are personified and given “voices.” There is an increased “depth of field” available to both clinicians as well as fellow group participants, allowing them to see themselves from many different vantage points. A helpful metaphor when facilitating these experiential groups has been to describe fellow group members as “mirrors,” reflecting back different aspects of themselves and illuminating previous blind spots of unawareness—recognizing themselves as the common denominator in every relationship they are in.

Clinicians focus on highlighting relational patterns as adaptive attachment strategies. Awareness of and interventions involving recurring patterns—particularly around stress and anxiety—is more helpful in facilitating long-term change than delving into specific problem resolution (e.g., putting out fires). Many therapists agree that process is more valuable than content (although a certain amount of content can clarify the process), or that focusing on content can result in a futile chase for details that won’t produce sustained change.

Therapists working in the program have described their work as a continuous growth process, both professionally and personally. As one therapist expressed, “Each week I see reflections of myself in the stories and struggles of our clients which helps me continue my growth as a professional and more importantly as a human.” In addition, personal self-care emerged as a key ingredient in this intensive work.

Program Evaluation

Very little empirical research is available to examine process and effectiveness of personal growth workshops. In order to develop an evaluation of these kinds of programs, the content of the interventions and exercises, as well as the stated goals of the program need to be analyzed and matched to a larger scientific literature examining similar constructs. For instance, the Breakthrough survival strategies were determined to be akin to maladaptive schema (Young et al., 2008) and thus were measured by the young schema questionnaire (YSQ-S3) before and after the workshop and up to twelve months later (Young, 2005). Attachment issues related to dysfunction in families of origin dysfunction was measured through a validated scale of attachment patterns and interpersonal functioning, the inventory of interpersonal problems (Horowitz, Alden, Wiggins, & Pincus, 2000). Reductions in overall distress were measured using the outcome questionnaire-45 (OQ-45) (Lambert, Gregersen, & Burlingame, 2004), and a measure of self-esteem called the Rosenberg self-esteem scale (Rosenberg, 1979). Changes in social support were examined using the social provision scale (SPS) (Zaki, 2009). Referring therapists, responding to mailed surveys sent six weeks after client completion of Breakthrough, provided reports of progress in therapy following participation in Breakthrough. Data from a twelve-month outcome study are currently being analyzed to examine change in target areas from program entry to program completion and over a twelve-month follow-up period after participation.

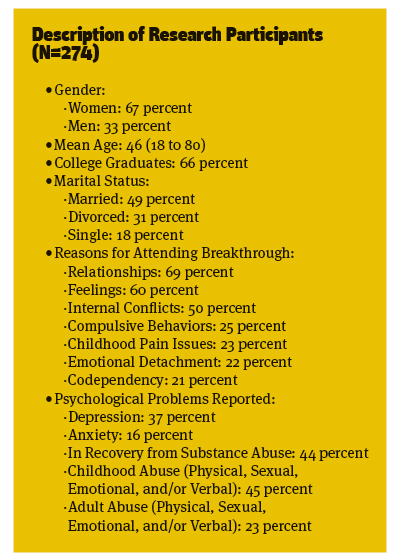

Overall, the most prevalent problem areas noted by participants as reasons for attending the Breakthrough personal growth workshop included relationships, feelings, internal conflicts, compulsions, childhood pain issues, emotional detachment, and codependency. Most (71 percent) of the participants had an outpatient therapist at entry to the workshop. Depression, anxiety, and recovery from an addictive substance were the most commonly reported psychological problems. A history of childhood abuse—physical, sexual, emotional, and/or verbal—and physical, sexual, emotional, and/or verbal abuse as an adult were common. Statistical analyses assessing change from baseline to a week after participation (retention rate=95 percent) and over a twelve-month follow-up (retention rate=64.6 percent) were examined using the measures previously described.

Preliminary results for improvement of symptoms after participating in the experiential, group-based program indicated that compared to baseline, participants had significant improvements on all measures at the end of the five-day program. In addition to the gains made during the treatment week, over the twelve-months following treatment, participants continued to report significant reductions on fourteen of the seventeen maladaptive schemas that were measured, and maintained improvements in symptom distress and maladaptive interpersonal behavior.

In terms of feedback from referring therapists, the study found generally positive results. Fifty-five percent of referring therapists reported their client’s feeling “less stuck in old patterns” after treatment and 73 percent of therapists said their client was more willing face “previously blocked issues.”

Case History

Matt is not a real individual, but represents a combination of clients’ stories typically seen in Breakthrough and the results that were found in this study. Matt, age forty-eight, was the father of two grown children and had worked for the same company for twenty years as a systems analyst manager. He was referred to Breakthrough by his therapist who described him as “shut down.” He was also strongly encouraged by his spouse who wanted him to access his emotions and increase intimacy in his marriage of twenty-four years. Matt’s stated problem was dissatisfaction in his relationship with his wife. His major complaint was that his wife was very critical and demanding of him. He felt that he could not “put up with it” for much longer. Resentment was building as he found himself unable to please her. In contrast, he reported feeling satisfied with all other areas of his life—work, sibling relationships, and social. The only exception was his relationship with his twenty-one-year-old son, which was strained and distant due to the son’s active drug abuse and recent admission to a treatment center.

Matt’s perception of himself was that he was a nice person and a good man who was being wrongly criticized in ways that he did not understand. He wanted a calm, happy, stress free marriage. When asked about his feelings around his marriage he said “It would be great if my wife could just let go and see the good things we have.”

He described his childhood history as “Fine,” “Okay I guess,” and “Pretty good.” He recalled his childhood as perfect until age five when his parents divorced. He did not remember closeness with anyone in particular. He felt that his parents did the best they could, but that feelings were never talked about. There was no history of abuse, but Matt admitted that he tended to distance himself from anything unpleasant in his family so he didn’t remember much.

During the first group session addressing attachment patterns Matt began by describing his wife’s problematic behavior toward him as the cause of all of his distress. He was encouraged to consider the possibility that his own withdrawal and distancing may increase his partner’s anxiety which then results in more defensive reactions. Several experiential exercises helped him open his mind to his lifetime pattern of passivity, withdrawal, and avoidance of conflict as a possible contributor to his struggle with his wife. The most significant change events for Matt were in the following areas.

Family Sculpture

Matt volunteered to play a role in a family sculpture of a hypothetical family. In role, he was the father and husband in a very active family with three children. His fictional wife was described by the Breakthrough therapist as a very decisive, hardworking, and busy—a perfectionist who was task-oriented. The husband’s role, played by Matt, was one of support, playing with the children, coaching their sports, doing outside chores, and working at his job. Through the years the couple’s relationship had become strained. The wife in this drama became overwhelmed with responsibilities and had frequent complaints. At the same time her husband became inattentive, forgetful and distant. They were no longer affectionate with each other and all activity revolved around the children and home. The therapist asked Matt and his “wife in role” to have a conversation this couple might have had at the end of a typical day of work. As the wife in this scenario became irritable and frustrated about her husband’s passivity, Matt—without being coached by the therapist—became quiet and compliant, offering to help out more, apologizing for being forgetful, and physically leaning away from her. The therapist then asked each partner to express to the group what they were really feeling and wanted to say to their role partner, but could not. Matt said he was afraid of her criticism and rejection and that he wanted to run away. He needed respect and acceptance from her. His “wife” said she wanted him to see her and be there when she needed him. She wanted him to be closer and by her side. This exercise was followed by processing with the group. Many members of the group understood and related to each of the partners in this relationship; Matt was not alone in his struggle. After this exercise Matt stated that “I just wanted to run out the door” and “I could not have spoken that openly because of my fear, but I want to be able to do that.”

Guided Imagery

In an imagery exercise focusing on grief, Matt reconnected with his feelings of loss when his father left their home during the divorce, and realized that the grief reminded him of the feelings he currently had about his son’s descent into drug use. Feeling like he was “losing” his son made Matt want to hide or distance himself from his son in order to avoid feeling the grief. Matt was given support from the group by commenting on the love he had for his son. He expressed gratitude for the empowerment he was feeling from their feedback.

Individual Psychodrama

In a fifty-minute session the therapists and group assisted Matt in setting up a role-play of a typical interaction with his wife. During the role-play he noticed that whenever his “wife” asked him a question, he felt blamed and wanted to withdraw by checking his e-mail or going outside. The group member playing the role of his wife was able to express her pain and loneliness when he did that. By reversing roles with his wife’s role-player he felt the pain of being ignored. Matt’s understanding of the emotional pain they were both experiencing in their conflicts set the stage for changes he wanted in their relationship. This solidified his realization that his silence and withdrawal from his wife were protecting him from pain but creating more distance between them. Matt bravely admitted to the group that he was not always honest with her because he was afraid of making things worse. He wanted to do better and needed to take the risk of being open and direct with her. At the end of his psychodrama Matt told his “wife” about his fear of her criticism and expressed his willingness to be honest and present in their marriage.

Starting with that first lecture on survival strategies and attachment patterns and continuing throughout the first two days of treatment, Matt was able to see his interactional patterns with his wife, and to begin to change his reactive, unassertive behavior in the context of the group. Through a peer group, for instance, he began to experience openness and emotional sharing without feeling defensive. He could also see the value of conflict. The psychodramas he witnessed and the roles he played for others provided deeper insights and emotions than he had ever experienced. In his personal family psychodrama he was able to see a connection between his past pain about his parents’ divorce and the current problems with his wife and son. Through Matt’s pre-post questionnaires, his showed improvement in self-esteem, healthier attachment patterns, and weakening of the maladaptive disconnection and rejection schema domain.

In summary, preliminary data suggest that the participants who attended the experiential, group-based, personal growth workshop in general experienced benefits from their work during the week. These benefits included improvements in well-being, self-esteem, maladaptive schemata, and interpersonal functioning. The brief but intensive group-based experiential format appears to be a viable platform for sustained change in behaviors, beliefs, and attachment styles long thought to be chronically resistant to improvement.

References

Gallo, L. C., Smith, T. W., & Ruiz, J. M. (2003). An interpersonal analysis of adult attachment style: Circumplex descriptions, recalled developmental experiences, self-representations, and interpersonal functioning in adulthood. Journal of Personality, 71(2), 141–81.

Gurtman, M. B. (1996). Interpersonal problems and the psychotherapy context: The construct validity of the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems. Psychological Assessment, 8(3), 241–55.

Horowitz, L. M., Alden, L. E., Wiggins, J. S., & Pincus, A. L. (2000). IIP inventory of interpersonal problems inventory manual. San Antonio, TX: PsychCorp.

Lambert, M. J., Gregersen, A. T., & Burlingame, G. M. (2004). The Outcome Questionnaire-45. In M. E. Maruish (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment: Volume 3: Instruments for adults (3rd ed.). (pp. 191–234). New York, NY: Routledge.

Obegi, J. H., & Berant, E. (2010). Attachment theory and research in clinical work with adults. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Rosenberg, M. (1979). Conceiving the self. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Smith, A. (1988). Grandchildren of alcoholics: Another generation of codependency. Deerfield Beach, FL: Health Communications.

Smith, A. (2013). Overcoming perfectionism, revised & updated: Finding the key to balance and self-acceptance. Deerfield Beach, FL: Health Communications.

Stuart, S., & Robertson, M. (2003). Interpersonal psychotherapy: A clinician’s guide (pp. 13–34). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Young, J. E. (2005). Schema-focused cognitive therapy and the case of Ms. S. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 15(1), 115–26.

Young, J. E., Rygh, J. L., Weinberger, A. D., & Beck, A. T. (2008). Cognitive therapy for depression. In D. H. Barlow (Ed)., Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual (4th ed.) (pp. 250–305). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Young, J. E., Klosko, J. S., & Weishaar, M. E. (2009). Schema therapy: A practitioner’s guide (pp. 13–21). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Zaki, M. A. (2009). Reliability and validity of the Social Provision Scale (SPS) in the students of Isfahan University. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 14(4), 439–44.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.