Share

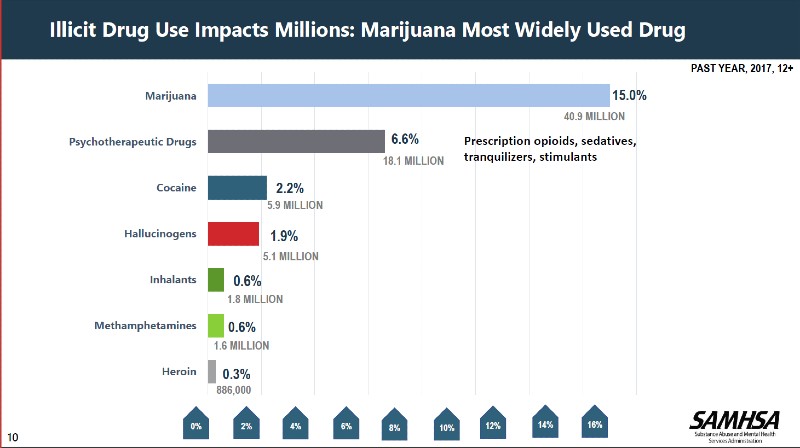

On Prevention Day 2019, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Assistant Secretary Elinore F. McCance-Katz declared that, “Marijuana is the most widely used drug in the United States.” For the professionals who work in the prevention and treatment fields, this is not a surprising or shocking statement. According to National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) data, 40.9 million Americans used marijuana over a one-year period (McCance-Katz, 2019). That is more than double the number of Americans that reported using prescription opioids at 18.1 million (McCance-Katz, 2019).

In 2018 the number of Americans that used marijuana increased to 43.5 million users (SAMHSA, 2019).

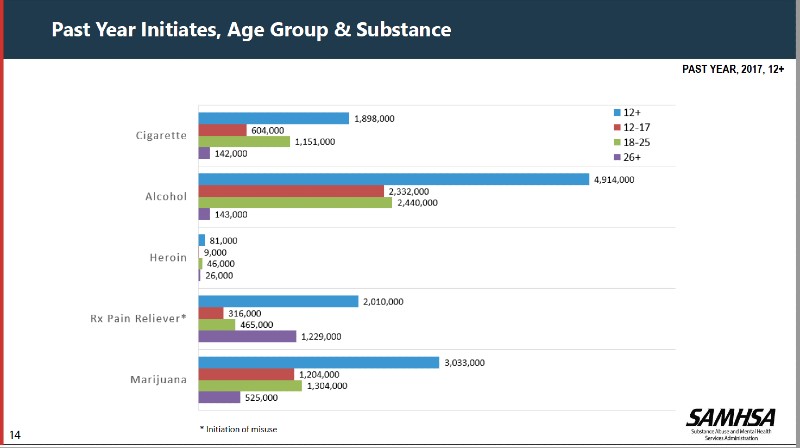

National data also reveal there has been an increase in marijuana use since 2002. Analysis of 2015–2017 NSDUH data show a 37 percent increase in overall marijuana use since 2007, with frequent use having increased by 37 percent since 2002 (McCance-Katz, 2019). Over three million respondents reported age of initiation of marijuana as twelve years and older. Marijuana initiation at this age group is second only to alcohol at over four million (McCance-Katz, 2019).

Results of the 2019 Monitoring the Future Survey showed a national increase in the daily use of marijuana in younger grades (Johnston et al., 2020). Additionally, over 6 percent of students in eighth grade and 18 percent of students in tenth grade reported using marijuana in the previous thirty days. Also, 22 percent of students in twelfth grade reported marijuana use within the previous month with more than 6 percent reporting daily use (Johnston et al., 2020). What is responsible for this increase in use across the United States?

The current marijuana landscape and change in perceptions regarding the harms of marijuana use may be responsible. In 1996, California became the first state in the nation to pass a comprehensive medical marijuana law (NCSL, 2020). Since then, thirty-six states have followed this trend. Fifteen states, including California, have legalized the recreational use of marijuana for adults age twenty-one and older (NCSL, 2020). When both medicinal and recreational use of a substance is made legal, there is a higher likelihood that the public will see the substance as less harmful. Declining perception of harm is a significant indicator to monitor because it is tied to the potential increase in use. In other words, the less a substance is viewed as harmful, the more likely people are to use it.

The Monitoring the Future data reported in 2016 that there was a 21 percent decrease in the national perception of harm associated with marijuana use since 2009 (Johnston, O’Malley, Miech, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2017). While underage use of marijuana remains illegal in California and other states where recreational use has been legalized, the perception of harm by youth continues to decline. In 2009, 52 percent of students in twelfth grade thought regular marijuana use was harmful, compared to 31 percent in 2016 (Johnston et al., 2017).

Data collected by the California Healthy Kids Survey (CHKS) show a slower decline in perception of harm (Austin, Hanson, Polik, & Zheng, 2018). However, monitoring this indicator over time will be necessary to identify and respond to shifts in perception. Data collected between 2015 and 2017 shows that perception of harm for both occasional and regular marijuana use decreased slightly for youth in grades nine and eleven only, with a one- to two-point change. This change, while lower than the national decline, still points to a lower perception of harm related to regular marijuana use (Austin et al., 2018).

The availability of and access to marijuana are important metrics that are predictors of youth use. With the advent of medical marijuana dispensaries, communities across the state have seen an increase in storefronts that have made marijuana, in various forms, more available to the public. Easier access for adults may also lead to easier access of marijuana in the home for youth. In California, youth have reported easy access to marijuana; based on CHKS data, half of ninth graders and two-thirds of eleventh graders found marijuana fairly—or even very easy—to obtain (Austin et al., 2018).

Marketing and promotion of medicinal and recreational marijuana has made it much more visible in the public sphere. While advertising restrictions have been in place for decades regarding legal substances like alcohol and tobacco, no such regulations are in place for marijuana. On average, youth are now exposed to more billboards, signage, and social media advertising for marijuana products. According to one study of approximately eight thousand youth with a mean age of thirteen, researchers found that sixth and eighth graders’ exposure to medical marijuana advertising was associated with both intentions to use marijuana and marijuana use one year later (D’Amico, Miles, & Tucker, 2015). This underlines the importance of regulations for marijuana advertising, similar to the regulations in place for tobacco and alcohol (D’Amico et al., 2015).

This increase in marketing and social media advertising is particularly concerning when it comes to youth, as young people are connected to social media now more than ever. Accessibility to social media “influencers” as well as information about marijuana and its supposed benefits of use (whether accurate or inaccurate) has skyrocketed. Also worrisome: marijuana is now available in multiple forms—it no longer needs to be smoked. The marijuana industry is filled with edibles and other THC products that are sweet or combined with sugary treats like candies, baked goods, and beverages, which arguably targets youth for consumption.

While state-level data does not currently show an increase in marijuana use by youth, national trends of increase in use, decrease in perception of harm, and increase in availability and promotion are important to monitor to ensure that protections are in place to prevent an increase in youth use as time progresses.

Risks Associated with Marijuana Use

While states have both legalized medicinal and recreational use of marijuana for adults, risks associated with frequent and long-term marijuana use by youth have been identified. Strong evidence exists that shows frequent youth marijuana use can impact brain functioning and development. This includes the following (Oleson & Cheer, 2012):

- Impaired decision-making

- Long-term effects on perception, reasoning, and judgment

- Verbal learning and memory impairments

- Increased risk of other substance use disorders

- Reduced reaction time

- Associations with mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety

The impact of youth marijuana use on cognitive development is more alarming when one realizes that today’s marijuana is stronger than in previous generations. On average, the THC content has risen from almost 4 percent in the 1990s to over 12 percent in 2014 (ElSohly et al., 2016). Considering the increase in potency of today’s marijuana, the full ramifications of marijuana’s impact on young people is still not fully known.

While both national and statewide data continues to emerge, there is evidence to suggest that marijuana use by youth can have negative ramifications for future substance use. Research conducted by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine concludes that there is substantial evidence that early initiation and frequency of marijuana use by young people is a risk factor that leads to cannabis addiction later in adulthood (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2017).

Another concern related to the growth of marijuana use is the national increase in marijuana-impaired driving. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine also found “substantial evidence of a statistical association between cannabis use and increased risk of motor vehicle crashes” (2017).

This is certainly a concerning risk factor considering young people are reporting higher rates of driving under the influence of marijuana versus alcohol. Results of one study show that of the 20 percent of youth that reported driving under the influence of marijuana, 34 percent believed their driving improved due to marijuana use (O’Malley & Johnston, 2013). In Washington, where alcohol- and drug-impaired driving is the leading contributing factor of fatal crashes, traffic safety survey results report that “52 percent of those who are driving under the influence of cannabis and alcohol are likely to feel too impaired after drinking and use cannabis to sober up” (Finely, 2019).

Recommendations for Addressing Youth Marijuana Use

With the legalization of adult use of marijuana, what approaches can be taken to address the general perception that marijuana is not harmful? How can the risks associated with youth use be addressed? Researchers note that approaches to addressing marijuana must take into consideration the unique differences related to the lack of perceived harm and the lack of immediate consequences from marijuana use. Providing better information on the long-term effects of youth marijuana use and its impact on developing brains will be key to changing the social norms related to marijuana use. Addressing the proliferation of marijuana marketing targeting youth, and then limiting youth access, may also reduce youth use. According to D’Amico and colleagues (D’Amico, Tucker, Pendersen, & Shih, 2017), specific prevention approaches include:

- Creating and disseminating accurate educational information on the impact of youth use and risks associated with use

- Creating campaigns, resources, and information to counter social norms promoting use

- Working with policymakers to develop and implement regulations that help to reduce access, availability, and use by adolescents

Prevention Strategies to Address Youth Marijuana Use: What Works?

While it may be too early to collect impact results for targeted prevention interventions for youth marijuana use, preventionists can utilize existing, evidence-based strategies that reduce the onset of substance use. Substance use disorder (SUD) prevention focuses on reducing the risk and protective factors associated with substance use for individuals as well as the social norms, availability, and accessibility of substances to reduce use in local environments regardless of the specific substance. SAMHSA’s Center for Substance Abuse Prevention (CSAP) developed six major categories for prevention activities found to be effective in preventing substance use (CSAP, 2017):

- Dissemination of information on substances

- Education on the impact and results of substance use

- Alternative activities to substance use

- Problem identification and referral

- Community-based processes to address social norms of substance use

- Environmental approaches to impact access and availability of substances in a community

These broad strategic prevention approaches provide the foundation for the development of programs, tools, and resources used by the prevention field to reduce marijuana use. While some strategies alone may have limited impact on individual behaviors related to substance use, incorporating multiple prevention strategies may be more effective in preventing long-term use. While all six strategies can be employed in a comprehensive community prevention approach, the most common prevention strategies to address marijuana use include information dissemination, education, and environmental approaches. These three strategies also align with research-based outcomes and recommendations to address youth use.

Information Dissemination

A long-standing SUD prevention strategy has been to disseminate accurate information regarding the impact of substance use and related risks. The influx of positive media messages tied to marijuana has increased over the last several years, and young people have been inundated with messages promoting marijuana use. Counteracting this approach with the provision of accurate information regarding the risks of youth marijuana use should be prioritized in order to prevent or decrease youth use. Research shows that “intervention and prevention programs must better address the effects of marijuana” while acknowledging that though there may be some medicinal benefits, “marijuana use can affect functioning during adolescence when the brain is still developing” (D’Amico et al., 2017).

Preventionists have learned over the years the most effective ways to communicate information on substance use. “Scare tactics” are no longer effective and are not the most impactful way to curb use by the general public. Instead, newer prevention approaches take into consideration sound marketing methods to ensure that preventative messages will not only be accurate—and without a doomsday hysteria—but will also be relevant and engaging for the focus population. This new approach of disseminating accurate information has been effectively used to combat existing positive social and community norms related to marijuana.

With the legalization of marijuana for adult use in California, youth, parents, and community members have been vocal in requesting information on how to talk to their children and peers about marijuana use. Prevention professionals have created numerous tools to equip youth and adults with sound, research-based information about the risks and impacts of marijuana use. These tools include social media campaigns, videos, websites, fact sheets, brochures, and public information and resources that present the impact of marijuana use in a factual, clear way. These resources have presented information about how marijuana impacts young people’s physical development, brain functioning, and future implications into adulthood. Developing and sharing accurate, research-based informational resources with the general public is a positive way to address the massive amount of inaccurate information shared by promarijuana advocates, supporters, and businesses.

See the bottom of the article for a list of several prevention resources developed to share accurate information on the effects of marijuana use.

Education

In the prevention field, the strategy of education is twofold: to provide youth with skills and abilities to make critical life decisions, and to provide them with nonjudgmental, facts-based information on the impact of substance use to help them make important life decisions. Prevention education curricula can take many forms, including module- and curriculum-based content, youth leadership development programming, and parent education. Programming can be implemented in both school and community settings. Existing curricula-based programs such as Caring School Community and Lifeskills Training outcomes have shown reductions in youth marijuana use.

The Caring School Community program was developed for youth in kindergarten through sixth grades with a focus on promoting positive youth development (Center for the Collaborative Classroom, 2020). The Lifeskills Training study—focusing on personal self-management skills, social skills, and resistance skills related to drug use—showed a 66 percent reduction in marijuana use among intervention group participants relative to controls (Botvin, Baker, Dusenbury, Botvin, & Diaz, 1995).

These are just two examples of education-based prevention programs that have been effective in reducing youth marijuana use. Additional programs, including study results, can be found at the Blueprints for Health Youth Development website operated by the University of Colorado Boulder (2020).

The Stanford School of Medicine has created innovative educational curricula to directly address youth marijuana use for educators and prevention professionals. While the Cannabis/Marijuana Awareness and Prevention Toolkit has just been finalized and released, it utilizes theory and evidence-informed educational approaches. Promoting the nonbiased approach, this new toolkit provides information on both the positive and the negative impact of marijuana use so youth can make informed decisions regarding use (Stanford Medicine, 2020).

Environmental Approaches

Environmental prevention strategies seek to bring about system-level change through the creation or modification of codes, legislation, ordinances, policies, and regulations related to substance use. The overarching goals are to limit access and availability of substances to bring about population-level change. Changing laws, implementing ordinances and regulations, and addressing outlet density can be extensive—it takes substantial time and effort by prevention professionals and partners including law enforcement, community organizations, affiliation groups, and, of course, lawmakers. However, the time and tenacity necessary is worthwhile as lack of existing marijuana policy is seen as a substantial risk factor for increased use. Research points to the need for regulations that can help reduce access and availability of marijuana by young people. The lessons learned from tobacco policy and regulation can be applied to marijuana (Pacula, Kilmer, Wagenaar, Chaloupka, & Caulkins, 2014).

Learnings from both alcohol and tobacco policy include the development of outlet density ordinances and taxation. Municipalities across California have coordinated efforts spearheaded by prevention professionals to create local ordinances related to licensing of medical marijuana dispensaries and recreational marijuana outlets and business tax requirements. The Public Health Institute (PHI) developed the Model Local Ordinance for Cannabis Taxation in California as a resource for California cities and counties to respond to legalization and outlet density in their communities (Silver & Colantuono, 2018).

Examples of alcohol outlet density ordinances have also been applied by to marijuana storefronts. Cities and counties have been able to create ordinances that ensure that outlets cannot be near schools and other child-centered businesses. Other ordinances have restricted the number of dispensaries in a community or neighborhood, thereby reducing access.

Environmental prevention efforts have also focused on addressing advertising and marketing in communities, at retail outlets, and on television commercials and in movies. In order to address the proliferation of advertising on new platforms such as social media, prevention professionals and lawmakers can work collaboratively to address this highly unregulated environment used to promote marijuana use.

Conclusion

Marijuana is currently the number one drug of use nationally (Azofeifa et al., 2016). While California data does not currently show an increase in use since legalization of recreational use, declining perception of harm (no matter how slight) requires all prevention and treatment professionals to closely monitor trends of use by young people across the state to prevent an increase in use.

In order to prevent an increase in use, prevention strategies can be used as the first line of defense to combat social norms, advertising, appeal, and availability of marijuana for youth. Proven prevention strategies successfully implemented to address and decrease alcohol and tobacco use in the past can be used to address youth marijuana use. These practices can help change the perception regarding positive social norms facing youth and communities in California and on the national level.

Marijuana Prevention Resources

- Ventura County Marijuana Fact Check: https://www.mjfactcheck.org/

- Center for Community Research Marijuana Prevention Initiative San Diego County: https://www.ccrconsulting.org/mpi

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Marijuana Research Report Series: https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/marijuana/what-marijuana

- Cannabis Decoded: San Mateo County: https://www.cannabisdecoded.org/

- SAMHSA: Know the Risks of Marijuana: https://www.samhsa.gov/marijuana

References

- Austin, G., Hanson, T., Polik, J., & Zheng, C. (2018). California Healthy Kids Survey: School climate, substance use, and well-being among California students, 2015–2017. Retrieved from https://data.calschls.org/resources/Biennial_State_1517.pdf

- Azofeifa, A., Mattson, M. E., Schauer, G., McAfee, T., Grant, A., Lyerla, R. (2016). National estimates of marijuana use and related indicators – National Survey on Drug Use and Health, United States, 2002–2014. Surveillance Summaries, 65(11), 1–25.

- Botvin, G. J., Baker, E., Dusenbury, L., Botvin, E. M., & Diaz, T. (1995). Long-term follow-up results of a randomized drug abuse prevention trial in a white middle-class population. JAMA, 273(14), 1106–12.

- Center for Substance Abuse Prevention (CSAP). (2017). Center for Substance Abuse Prevention strategies and CSAP activities: Definitions. Retrieved from http://www.ca-cpi.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/CSAP-Strategies.pdf

- Center for the Collaborative Classroom. (2020). Caring school community, K-8: SEL and discipline reimagined. Retrieved from https://www.collaborativeclassroom.org/programs/caring-school-community/

- D’Amico, E. J., Miles, J. N. V., & Tucker, J. S. (2015). Gateway to curiosity: Medical marijuana ads and intention and use during middle school. Psychology of Addictive Behavior, 29(3), 613–9.

- D’Amico, E. J., Tucker, J. S., Pedersen, E. R., & Shih, R. (2017). Understanding rates of marijuana use and consequences among adolescents in a changing legal landscape. Current Addiction Reports, 4(10), 343–9.

- ElSohly, M. A., Mehmedic, Z., Foster, S., Gon, C., Chandra, S., & Church, J. C. (2016). Changes in cannabis potency over the last two decades (1995–2014): Analysis of current data in the United States. Biological Psychiatry, 79(7), 613–9.

- Finely, K. (2019). Exploring Washington State’s traffic safety culture about driving under the influence of cannabis and alcohol. Presentation at the National Prevention Network Conference on August 29, 2019 in Boston, MA. Retrieved from http://npnconference.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/NPN_Exploring-Washington-States-Traffic-Safety-Culture-about-DUICA.pdf

- Johnston, L. D., Miech, R. A., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., Schulenberg, J. E., & Patrick, M. E. (2020). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2019. 2019 overview: Key findings on adolescent drug use. Retrieved from http://www.monitoringthefuture.org//pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2019.pdf

- Johnston, L. D., O’Malley, P. M., Miech, R. A., Bachman, J. G., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2017). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use. 2017 overview: Key findings on adolescent drug use. Retrieved from http://www.monitoringthefuture.org//pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2016.pdf

- McCance-Katz, E. F. (2019). Urgent and emerging issues in prevention: Marijuana, kratom, e-cigarettes. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/samhsas-15th-annual-prevention-day-afternoon-plenary-recording.pdf

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2017). The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: the current state of evidence and recommendations for research. Retrieved from https://www.nap.edu/read/24625/chapter/1#ii

- National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL). (2020). State medical marijuana laws. Retrieved from https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-medical-marijuana-laws.aspx

- Oleson, E. B., & Cheer, J. F. (2012). A brain on cannabinoids: The role of dopamine release in reward seeking. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine, 2(8).

- O’Malley, P. M., & Johnston, L. D. (2013). Driving after drug or alcohol use by US high school seniors, 2001–2011. The American Journal of Public Health, 103(111), 2027–34.

- Pacula, R. L., Kilmer, B., Wagenaar, A. C., Chaloupka, F. J., & Caulkins, J. P. (2014). Developing public health regulations for marijuana: Lessons from alcohol and tobacco. The American Journal of Public Health, 104(6), 1021–8.

- Silver, L., & Colantuono, M. G. (2018). Model ordinance regulating local cannabis retail sales and marketing in California. Retrieved at https://www.phi.org/thought-leadership/model-ordinance-regulating-local-cannabis-retail-sales-and-marketing-in-california/

- Stanford Medicine. (2020). The cannabis/marijuana awareness & prevention toolkit. Retrieved from http://med.stanford.edu/cannabispreventiontoolkit/about.html

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2019). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reportsNSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018.pdf

- University of Colorado Boulder. (2020). Blueprints for healthy youth development. Retrieved from https://www.blueprintsprograms.org/

About Me

Erika Green, MS, CCPS, ICPS, has twenty-two years of experience providing direct service, management, training, and field support at the local, statewide, and national level in youth substance use disorder (SUD) prevention and youth mentoring program services. She is currently the associate executive director at the Center for Applied Research Solutions (CARS) and is the Community Prevention Initiative (CPI) project director, providing training and support to the SUD prevention field in California.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.