Clinicians working in adolescent substance use treatment programs know that youth they see frequently have co-occurring mental health problems that need to be addressed during treatment. Studies report that between 55 percent and 88 percent of youth presenting for substance use treatment also meet criteria for a psychiatric disorder, most commonly conduct disorder, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, anxiety, and disorders related to traumatic stress (Chan, Dennis, & Funk, 2008; Diamond et al., 2006). Current research suggests these youth have more severe problems, are more difficult to engage and retain in services, and have worse substance use outcomes than those without co-occurring disorders (CODs) (Grella, Joshi, & Hser, 2004; Shane, Jasiukaitis, & Green, 2003; Winters, Stinchfield, Latimer, & Stone, 2008).

To address these youths’ needs, experts have made the case for the delivery of integrated treatments that address both substance use and CODs. Recommended components of integrated treatment are:

- A comprehensive assessment that helps identify both substance use and psychiatric problems

- A clinical approach that uses empathic and nonconfrontational engagement and retention techniques, while being collaborative with youth to create treatment plans

- Inclusion of several skill-based training techniques such as problem solving and decision making, affect regulation, impulse control, communication, peer and family relations, and medication monitoring and adherence

- The inclusion of family and community resources

- Use of developmentally appropriate and gender- and culturally competent methods

- Use of homework assignments to assist youth in practicing skills learned during sessions outside of the treatment setting

Finally, experts have noted the strong need for clinical training to implement integrated treatments.

The Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach (A-CRA) is an empirically-supported treatment for adolescent substance use problems that incorporates many of the components described above as essential for integrated treatment. While originally developed as the Community Reinforcement Approach for adults (Azrin, Sisson, Meyers, & Godley, 1982; Hunt & Azrin, 1973), it has since been successfully adapted, manualized, and tested for use with adolescents with substance use disorders (Dennis et al., 2004; Godley, Godley, Dennis, Funk, & Passetti, 2007; Slesnick, Prestopnik, Meyers, & Glassman, 2007). Rates of treatment engagement, retention, satisfaction, and substance use outcomes have been high and similar across gender and racial/ethnic groups (Godley, Hedges, & Hunter, 2011).

A-CRA involves the community in youths’ treatment. For example, family, friends, school, job, and other organizations are considered critical to the treatment and recovery process. Confrontation is avoided, and positive reinforcement and other behavior change principles are used to shape greater involvement in prosocial activities (Azrin, 1976; Hunt & Azrin, 1973). Clinicians attempt to increase youths’ access to and engagement in prosocial activities so that those activities compete with time spent using substances, thereby increasing abstinence and positive recovery. A-CRA consists of nineteen procedures, including problem-solving skills, communications skills, relapse prevention, and medication monitoring/adherence, which clinicians can choose from according to youth needs during sessions. Specific sessions are designed for parents and/or caregivers alone and with their youth (Godley et al., 2001; Meyers & Smith, 1995).

Given the prevalence of CODs among youth entering substance use treatment, the widespread dissemination of A-CRA, and that the intervention has several key features of effective treatments for common mental health problems, a study was designed to learn more about treatment engagement and outcomes for youth with and without co-occurring problems who received A-CRA treatment. Data were analyzed from 5,150 youth that were part of a large grant initiative funded by the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT) of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) to disseminate A-CRA in the United States (Godley, Smith, Passetti, & Subramaniam, 2014).

A-CRA Dissemination Project and Participant Groups

Seventy-eight substance use treatment organizations across twenty-six states and a mixture of urban and rural areas were part of the CSAT-funded project. A training and certification process that included ratings of recorded sessions was developed to ensure clinicians learned to deliver A-CRA with fidelity (Godley, Garner, Smith, Meyers, & Godley, 2011). Most were community-based nonprofit organizations. Youth participants served by the organizations represented a broad range of races/ethnicities, including those who reported being African American, Caucasian, Hispanic, American Indian, and mixed race/ethnicities. While the percentage of female youth participants at each agency varied, 26 percent across all agencies were female. A-CRA was delivered in outpatient clinics, schools, youth homes, or a mixture of settings with a planned duration of twelve to fourteen weeks. The Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN; Dennis, Titus, White, Unsicker, & Hodgkins, 2003) was used to collect data on youth problems and outcomes. Based on information gathered during GAIN assessments at intake into A-CRA treatment, youth were divided into the following four groups for analysis (Godley et al., 2014):

- Non-comorbid (i.e., youth reporting symptoms of substance use disorder only/no CODs; 36 percent)

- Internalizing (i.e., youth reporting symptoms of a substance use disorder and co-occurring depression, anxiety, and/or traumatic stress; 8 percent)

- Externalizing (i.e., youth reporting symptoms of a substance use disorder and co-occurring conduct disorder and/or ADHD; 22 percent)

- Mixed (i.e., youth reporting symptoms of a substance use disorder and both internalizing and externalizing disorders; 34 percent)

Internalizing Group

Compared to youth who were non-comorbid, those youth who were categorized as in the internalizing and substance user group were more likely to have the following characteristics:

- Be female

- Identify themselves as mixed race

- Report drugs other than alcohol, marijuana, and amphetamines as their drug of choice

- Have more substance use and emotional problems

- Report higher rates of victimization in the ninety days prior to intake into treatment

- Report higher rates of HIV risk behaviors

Youth in this group were less likely to identify themselves as African-American or Hispanic; come from a single parent household; be involved in the criminal justice system; report marijuana as their primary drug of choice; and report more days of abstinence from substance use.

Externalizing Group

Compared to youth who were non-comorbid, those youth who were categorized in the externalizing and substance user group were more likely to have these characteristics:

- Identify themselves as mixed race or Caucasian

- Report marijuana as their primary drug of choice

- Report more substance use and emotional problems

- Report more victimization in the ninety days prior to treatment intake

- Report higher rates of HIV risk

Youth in this group were less likely to be older; identify themselves as Hispanic; report amphetamines as their primary drug of choice; and report more days of abstinence from substance use.

Mixed

Compared to youth who were non-comorbid, those youth who were categorized in the mixed group—that is, youth who were experiencing both internalizing and externalizing symptoms along with substance use—were more likely to have the following characteristics:

- Be female

- Identify themselves as mixed race or Caucasian

- Report alcohol or drugs other than alcohol, marijuana, and amphetamines as their primary drug of choice

- Report more substance use and emotional problems

- Report more victimization in the ninety days prior to intake

- Report higher rates of HIV risk

Youth in this group were less likely to identify themselves as African-American or Hispanic; be involved with the criminal justice system; report marijuana or amphetamines as their primary drug of choice; and report more days of abstinence from substance use.

A-CRA Participation and Treatment Retention and Satisfaction

All four groups of youth participated in A-CRA treatment to a similar extent. They attended similar numbers of A-CRA treatment sessions overall and similar numbers of youth-only, caregiver-only, and family sessions. Additionally, they initiated and engaged in A-CRA at similar rates and reported similar levels of treatment satisfaction when assessed at three months after admission. Initiation was defined as receiving a second treatment session within fourteen days of the first, and engagement was defined as receiving at least two additional sessions within thirty days of the initiation date. At six and twelve months after intake, when youth were no longer enrolled in their initial A-CRA treatment episode, there were no differences in days of mental health treatment received. However, youth in the internalizing group received fewer days of substance use treatment than the non-comorbid group between months ten and twelve.

A-CRA Participation and Substance Use and Emotional Problem Outcomes

Youth with CODs (i.e., youth in the externalizing, internalizing, or mixed groups) reported a significantly higher percentage of days using alcohol or any drug at intake when compared with those in the non-comorbid group. Over time, externalizing and mixed group youth had significantly larger rates of increase in the percent of days abstinent as compared to the non-comorbid group. The internalizing group was not different from the non-comorbid group in terms of the rate of change.

Similarly, youth with CODs reported a significantly higher number of substance problems at intake than those in the non-comorbid group. The externalizing and mixed groups had significantly larger rates of decrease in substance problems as compared to the non-comorbid group. The internalizing group was not different from the non-comorbid group in terms of the rate of change.

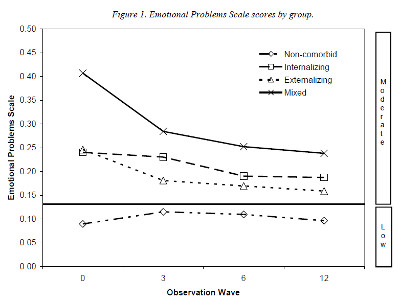

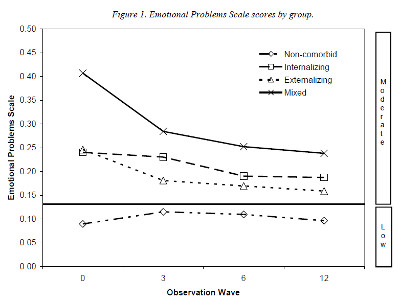

In terms of emotional problems, youth with CODs reported a significantly higher severity of emotional problems than the non-comorbid group at intake as measured by the GAIN Emotional Problems Scale. Youth with CODs also had significantly larger rates of decrease in emotional problems over time than the non-comorbid group (see Figure 1).

Clinical and Research Implications

There are several findings from this study that are useful to clinicians and researchers. First, it was possible to summarize characteristics of youth in the four groups. For example, being female was associated with an increased chance of being categorized as internalizing or mixed. Also, youth who identified themselves as mixed race were more likely to have a COD, and Caucasian youth were more likely to fall into the externalizing or mixed groups. Youth in the externalizing group were slightly younger than those with only a substance use disorder.

Second, substance use data suggested that, consistent with other research, youth with CODs entered substance use treatment with more days of substance use and greater levels of substance use problems than non-comorbid adolescents. Contradicting other research, findings indicated that youth with CODs were able to initiate and engage in treatment at similar rates as non-comorbid youth. There were also similar rates of retention during the A-CRA treatment episode. One possible explanation is that delivering an empirically-supported treatment may have helped improve engagement and retention rates for youth with multiple problems.

Third, substance use and emotional problem outcomes at six and twelve months after intake showed that youth with CODs responded to A-CRA. These youth increased in abstinence and decreased in substance use at the same or greater rates than non-comorbid youth. While youth classified in the internalizing group were not different from the non-comorbid group in terms of change in percent of days abstinent, the externalizing and mixed groups had significantly greater increases in days of abstinence. Likewise, the externalizing and mixed groups showed significantly greater decreases in substance use problems when compared with the non-comorbid group, while there was no difference between the internalizing and non-comorbid groups. Overall, youth with CODs had significantly greater decreases in emotional problems than the non-comorbid group. Despite this decrease, the group of youth with CODs continued to report emotional problems at a somewhat higher rate than the non-comorbid group.

An important strength of this study is that data were collected from a large and diverse sample of youth presenting to substance use treatment organizations throughout the United States. Such a large and diverse sample suggests that results are more generalizable to youth across the country than a study with a small number of participants from one or two sites. Also, the large sample size allowed the composition of four groups representing different COD categories to be identified and analyzed. Finally, this was one of only a few studies that analyzed data obtained from the dissemination and implementation of an empirically-supported substance use treatment for adolescents that included both training and ongoing supervision to maintain model fidelity.

There were also some limitations to this study that should be addressed in future research in this area. Assessments from several agencies and participants were not included in the analysis due to low follow-up rates at those sites. While dropping some site data could possibly skew findings, analysis of intake characteristics indicated that youth from those sites did not differ from those who were included in the analytic sample on any characteristic except for age. Second, self-reported substance use was not corroborated by bio-marker or collateral reports. Nevertheless, youth self-report measures of substance use from the GAIN have been shown to be consistent with collateral reports and urine tests. Third, it is unknown if findings from this study apply to youth receiving substance use treatment other than A-CRA.

Conclusion

In summary, even though youth with CODs had higher levels of substance use and emotional problems at twelve months after intake than the non-comorbid group, the gap in severity shrank between the externalizing and mixed groups and the non-comorbid group. Additionally, youth with CODs improved on all outcomes at a faster rate than non-comorbid youth. The externalizing group in particular improved as much as or more than the internalizing and mixed groups and made larger improvements overall when compared to the internalizing group. Youth in the externalizing group achieved the highest rates of abstinence, the lowest number of substance problems, and the lowest number of emotional problems at twelve months after intake when compared with the internalizing and mixed groups. While the mixed group had the most substance and mental health problems at twelve months out of all the groups, they had the largest decreases in the measures examined. They showed significant increases in abstinence that peaked at three months after intake into A-CRA and remained that way out to twelve months.

Overall, findings are the most encouraging for youth with externalizing problems since this study provides evidence that significant positive changes can be made in their substance use and related problems and that these changes can persist up to twelve months after admission to A-CRA treatment. Further research is needed to determine whether A-CRA would benefit from augmenting current procedures in order to directly target specific comorbid symptoms. Nonetheless, youth in the current study did experience notable improvements, suggesting that A-CRA offers promise as an integrated treatment option for youth with CODs, and thus warrants further clinical application and study.

Acknowledgments: Support for this study was provided by HHSS270201200001C, No. 270-12-0397 and R01 AA021118-01A1. The authors wish to thank the SAMHSA Center for Substance Abuse Treatment grantees and their patients; Brooke Hunter, Dr. Sergio Fernandez-Artamendi, Dr. Jane Smith, and Dr. Robert Meyers for their work on the original manuscript for the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment; Dr. Geetha Subramaniam and Dr. Jane Ellen Smith for their work on a related paper; and Kelli Wright for manuscript preparation. The opinions are those of the authors and do not reflect official positions of the contributing grantees project directors or the federal government.

References

Azrin, N. H. (1976). Improvement in the community reinforcement approach to alcoholism. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 14(5), 339–48.

Azrin, N. H., Sisson, R. W., Meyers, R., & Godley, M. D. (1982). Alcoholism treatment by disulfiram and community reinforcement therapy. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 13(2), 105–12.

Chan, Y. F., Dennis, M. L., Funk, R. R. (2008) Prevalence and comorbidity co-occurrence of major internalizing and externalizing disorders among adolescents and adults presenting to substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 34(1), 14–24.

Dennis, M. L., Godley, S. H., Diamond, G., Tims, F. M., Babor, T., Donaldson, J., . . . Funk, R. R. (2004). The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) Study: Main findings from two randomized trials. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 27(3), 197–213.

Dennis, M. L., Titus, J. C., White, M., Unsicker, J., & Hodgkins, D. (2003). Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN): Administration guide for the GAIN and related measures. Bloomington, IL: Chestnut Health Systems.

Diamond, G., Panichelli-Mindel, S. M., Shera, D., Dennis, M., Tims, F., & Ungemack, J. (2006). Psychiatric syndromes in adolescents with marijuana abuse and dependency in outpatient treatment. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse, 15(4), 37–54.

Godley, S. H., Garner, B. R., Smith, J. E., Meyers, R. J., & Godley, M. D. (2011). A large-scale dissemination and implementation model. Clinical Psychology, 18(1), 67–83.

Godley, M. D., Godley, S. H., Dennis, M. L., Funk, R. R., & Passetti, L. L. (2007). The effect of assertive continuing care on continuing care linkage, adherence, and abstinence following residential treatment for adolescents with substance use disorders. Addiction, 102(1), 81–93.

Godley, S. H., Hedges, K., & Hunter, B. (2011). Gender and racial differences in treatment process and outcome among participants in the Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 25(1), 143–54.

Godley, S. H., Meyers, R. J., Smith, J. E., Karvinen, T., Titus, J. C., Godley, M. D., . . . Kelberg, P. (2001). Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach (ACRA) for adolescent cannabis users: Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) manual series, vol. 4. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Godley, S. H., Smith, J. E., Passetti, L. L., & Subramaniam, G. (2014b). The Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach (A-CRA) as a model paradigm for the management of adolescents with substance use disorders and co-occurring psychiatric disorders. Substance Abuse, 35(4), 352–63.

Grella, C. E., Joshi, V., & Hser, Y.-I. (2004). Effects of cormorbidity on treatment processes and outcomes among adolescents in drug treatment programs. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse, 13(4), 13–31.

Hunt, G. M., & Azrin, N. H. (1973). A community-reinforcement approach to alcoholism. Behavior Research and Therapy, 11(1), 91–104.

Meyers, R. J., & Smith, J. E. (1995). Clinical guide to alcohol treatment: The Community Reinforcement Approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Shane, P. A., Jasiukaitis, P., & Green, R. S. (2003). Treatment outcomes among adolescents with substance abuse problems: The relationship between comorbidities and posttreatment substance involvement. Evaluation and Program Planning, 26(4), 393–402.

Slesnick, N., Prestopnik, J. L., Meyers, R. J., & Glassman, M. (2007). Treatment outcome for street-living, homeless youth. Addictive Behaviors, 32(6), 1237–51.

Winters, K. C., Stinchfield, R. D., Latimer, W. W., & Stone, A. (2008). Internalizing and externalizing behaviors and their association with the treatment of adolescents with substance use disorder. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 35(3), 269–78.

Editor’s Note: This article was adapted from an article by the same authors previously published in the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment (JSAT). This article has been adapted as part of Counselor’s memorandum of agreement with JSAT. The following citation provides the original source of the article:

Godley, S. H., Hunter, B. D., Fernandez-Artamendi, S., Smith, J. E., Meyers, R. J., & Godley, M. D. (2014). A comparison of treatment outcomes for adolescent community reinforcement approach participants with and without co-occurring problems. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 46, 463–71.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.