LOADING

Share

In a hospital setting, patients can present with substance use or problems associated with substance misuse. Additionally, unhealthy alcohol use contributes to hospitalizations, especially for traumatic injuries as well as chronic health issues such as neuropsychiatric disorders, gastrointestinal diseases, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes (WHO, 2014). In addition to intoxication, withdrawal, and overdose, substance use is associated with motor vehicle accidents, violent acts, and loss of workplace productivity (ONDCP, 2004). Intoxicated trauma center patients are 2.5 times more likely to be readmitted for another injury and those with a chronic alcohol problem are 3.5 times more likely to be readmitted (Rivara, Koepsell, Jurkovich, Gurney, & Soderberg, 1993). The US Department of Justice National Drug Intelligence Center estimated the cost of substance use was $193 billion in 2011 (2011) and alcohol use has been attributed to eighty-five thousand US deaths each year (Saitz, 2013).

Although only 5 percent of US adults are screened as alcohol dependent, about 25 percent engage in risky or harmful use including binge drinking, leaving 70 percent as low-risk or nondrinkers (ENA, 2008). The Institute of Medicine (IOM), when charged with developing strategies for improving US health quality including substance abuse, recommended community-based screenings for health risk behaviors as well as appropriate assessment and referrals (IOM, 2001). The same IOM report identified Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) as a promising practice to be used in primary care settings (SAMHSA-HRSA, 2002). The IOM recommendation was supported by a meta-analysis of 360 controlled trials on alcohol treatment, which found that screening and brief interventions were the most effective of more than forty approaches (SAMHSA-HRSA, 2002).

More recently, the Joint Commission for the Accreditation of Health Care Organizations—which accredits 95 percent of US hospital beds—approved new performance standards in 2011 called “Core Measures,” which evaluate among other things: hospital rates of inpatient screening for unhealthy alcohol use, brief interventions for patients demonstrating high-risk alcohol use, alcohol and drug dependence treatment, and specific referrals at discharge and follow-up to assess postdischarge substance use and engagement into treatment (The Joint Commission, 2014). Consequently, the groundwork was laid for hospital brief interventions and the growing activities in primary health care to identify patients at risk for substance abuse, to provide brief interviews and advice on alcohol and drug use, and to connect patients with community resources to decrease or discontinue their use.

After an introduction of SBIRT, this article describes a partnership program within University of Kentucky HealthCare called Mentoring Angels, which enhances SBIRT interventions with follow-up contacts by trained volunteers. In addition, case examples are presented.

Methods

SBIRT is a brief, evidence-based intervention to identify, reduce, and prevent problematic substance use, abuse, and dependence. More specifically, SBIRT interventionists provide early intervention and referral to treatment services for persons with substance use disorders (SUDs) and identify those at risk of developing these disorders (OMNI Institute, 2012). From a public health perspective, the reasoning behind SBIRT is clear: by addressing patient’s alcohol and drug use behaviors systematically, reduced health care needs and associated costs related to illness, hospitalizations, trauma, and accidents can be achieved. Research demonstrates that SBIRT reduces health care cost, severity of continued drug and alcohol use, and risk of trauma. These studies estimate savings of $3.81–$5.60 for every dollar invested in SBIRT (SAMHSA-HRSA, 2002). Other studies indicate that SBIRT patients experience 20 percent fewer emergency department visits, 33 percent fewer nonfatal injuries, 37 percent fewer hospitalizations, 46 percent fewer arrests, and 50 percent fewer motor vehicle crashes (SAMHSA-HRSA, 2002).

SBIRT enables health care professionals to screen individuals who may not otherwise seek help for a substance use problem. With SBIRT, abstainers and low-risk users are praised and reinforced for positive and healthy choices. Nondependent, at-risk drinkers are provided a brief intervention using motivational interviewing (MI) to increase awareness of the negative effects of substance use and to increase motivation to change risky use (SAMHSA-HRSA, 2002). Dependent substance users receive resources and referrals for additional services and for specialized help. SBIRT includes the following four approaches.

Screening (S)

Screening is a quick, straight-forward, and empirically supported approach to identify patients who use substances at a risky or hazardous level and who may meet the criteria for a SUD. Validated screening instruments include the AUDIT, or the abbreviated version AUDIT-C, ASSIST, and the CAGE. UK HealthCare patients who are admitted for inpatient care are asked the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) national norm questions followed by the CAGE if appropriate. The NIAAA screens for quantity and frequency of alcohol use to identify at-risk drinkers. Patients with drinking over the national norms for age and gender or with a positive CAGE are referred for a brief intervention. UK HealthCare also uses a question to screen for potential drug misuse. An affirmative answer to the following question also triggers a brief intervention: How many times in the past year have you used an illegal drug or prescription medication for nonmedical reasons?

Brief Intervention (BI)

The intervention is a short, five to fifteen minute “negotiated” interview to facilitate patients’ motivation to change their drinking or drug use patterns. The brief intervention provides information and feedback to a patient about drinking or drug use after reviewing their intake screen, blood alcohol content (BAC), and urine drug screen (UDS). Also, if applicable, linking their use of alcohol and other drugs to the reason they are hospitalized. During the brief intervention, there is an attempt to understand the patients’ view of their drinking and drug use and to enhance their motivation to change. The interventionist engages patients in a conversation using MI (Miller and Rollnick, 1991). A patient-centered dialogue considers the patients’ decisions about substance use and provides clear and respectful professional advice about reducing or abstaining to avoid high-risk situations or medical complications. The patients’ readiness for change determines the intervention strategy. Optimally, through this dialogue patients are guided to establish and articulate their own goals and, with the brief interventionist, develop a plan to achieve them. MI is used to initiate positive behavioral changes and support better health. In addition to MI, SBIRT incorporates the stages of change in the Transtheorectical Model of Behavior Change (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1977).

Referral (R) to Treatment (T)

If patients are identified within the change stage of contemplation or preparation, referrals are made for treatment or intervention. Referral can also include further evaluation by a substance abuse professional. Patients are given a list of local and national resources. Local resources can include outpatient mental health therapists, intensive outpatient programs, Twelve Step programs like Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) or Narcotics Anonymous (NA), and educational information.

When patients indicate that they would like additional assessment or treatment, a variety of options are discussed. Treatment options include detoxification, outpatient treatment, intensive outpatient treatment, residential treatment, and medication-assisted outpatient treatment. A referral to a substance abuse professional can determine the appropriate level of treatment and a more in-depth conversation about available options. Patients can also receive recovery support group literature including information about AA, NA or Celebrate Recovery.

Early alcohol research on brief interventions has shown that interventions by trained medical staff have good outcomes with at-risk drinkers but are less effective for chronic alcohol users (SAMHSA-HSRA, 2002). A study conducted by Blondell et al. (2001) found that volunteer peer mentors who were recovering alcoholics could meet with patients identified by physicians. Findings also showed promising results with reductions in drinking six months after discharge in addition to attending follow-up AA community meetings. UK HealthCare patients are provided the opportunity for a voluntary additional service through Mentoring Angels. The Angels are specially trained volunteers who talk with patients about their own recovery and community resources.

Mentoring Angels

Mentoring Angels is a low cost, novel approach to substance abuse. By utilizing the recovery community, patients are receiving education and follow-up and hospital staff are updated on issues related to addictions. In our experience, early support provided by compassionate volunteers can increase the chance that patients will reduce or stop their substance abuse. This early support simultaneously puts patients more at ease, making medical treatment more effective, and decreasing the number of patients leaving the hospital against medical advice. Mentoring Angels benefits the volunteers themselves, patients, the hospital, and the community.

Mentoring Angels is grounded in an approach developed by Blondell et al. (2001). Specifically, after a brief interventionist provides an intervention and referral to treatment, a Mentoring Angels volunteer, if requested by the patient, can help support treatment and recovery. The Mentoring Angels concept was developed by Mike Barry for The Healing Place in Louisville, KY. Mr. Barry worked as a counselor for The Healing Place with Dr. Blondell at the University of Louisville.

The University of Kentucky Healthcare and Chrysalis House, a community treatment program, collaborated to develop a volunteer peer support program called Mentoring Angels. The idea of peer support is not new; the founders of AA grounded AA on the idea of one alcoholic working with another to promote sobriety. The twelfth Step of AA is: “Having had a spiritual awakening as the result of these Steps, we tried to carry this message to alcoholics and to practice these principles in all our affairs” (Alcoholics Anonymous, 1994). The sharing of personal experience is the backbone of Twelve Step recovery. In the early history of AA, recovering alcoholics were reportedly discouraged by what seemed to be a hopeless endeavor to “save” other alcoholics. Once it was discovered that sharing your personal struggles as an alcoholic with other active users was actually beneficial to the one in recovery, the trajectory of service work was changed. Consequently, this is considered vital to a Mentoring Angels volunteer and to the patient.

A service like Mentoring Angels is beneficial for other reasons as well. Many patients hospitalized for alcohol- and drug-related problems have inaccurate notions about AA and NA. Meetings are often referred to as “classes” and there is much misinformation about the facilitators of these meetings. Some believe there are roll calls, mandatory attendance, and police officers ready to arrest those attending meetings. In our experience most patients have heard about AA and/or the Twelve Steps but aren’t sure they work or believe they have “fallen too far” to be helped. Treatment programs are often presented as the “cure” and a person is incurable if he or she uses after treatment. In Kentucky there are a limited number of treatment centers, which results in long waiting lists ranging from a few weeks to months. Mentoring Angels volunteers can speak openly, helping to ease the patient’s transition from the hospital to the community.

Our first Mentoring Angels referral was a female trauma patient who was contacted in October 2010. When meeting with patients, often deemed agitated and uncommunicative, Mentoring Angels volunteers discovered scared and lonely patients who had few visitors. Many patients longed for conversation, unconditional acceptance, and information volunteers provided. To date, Mentoring Angels has grown to over eight hundred patient contacts.

Through contact with addicted patients, Mentoring Angels volunteers learned that many patients have a limited understanding of addiction. The limited time spent with a brief interventionist does not necessarily address all the patient’s questions and concerns. In contrast, Mentoring Angels volunteers provide time for extended discussions and opportunities to dispel myths and misunderstandings about sobriety. Volunteers are able to provide realistic expectations, and offer their life experience and sobriety strategies. Mentoring Angels allows each volunteer’s past to help others change, something many volunteers once thought impossible. Most patients leave the hospital unprepared to face the problems from which they tried to escape through drug and alcohol use. This is when a Mentoring Angels contact could potentially save a life. For a patient, the connection to a person in recovery and involved in the Twelve Steps can be very meaningful. Likewise, volunteers can learn more about listening to others without judgment, rather than immediately attempting to “fix” things or to soothe quickly. Similarly to Twelve Step meetings, Mentoring Angels volunteers wait and listen, which models and helps develop listening skills. Because Mentoring Angels volunteers have taken active, healthy steps in their recovery, their collective wisdom benefits the patients and the hospital staff by creating an atmosphere of compassionate care. SBIRT interventionists complete a bedside brief intervention and when appropriate, ask for verbal patient consent to have volunteers from Mentoring Angels speak with them about their own recovery experience. Dependent on the patients’ stage of change, they receive information and education about treatment options, support groups, and are provided with a description of the Mentoring Angels service. If patients consent, the Mentoring Angels Coordinator is contacted to initiate the service. Consistent with the traditions of AA and NA, Mentoring Angels volunteers are paired by gender. Patients are provided a dedicated Mentoring Angels telephone number as well as information about local AA and NA meetings.

UK HealthCare supports Mentoring Angels with a convenient office, which is the hub of volunteer activity. A secure database of contact information is hosted on a dedicated site. The office is filled with brochures about treatment facilities, AA and NA materials, and other resources. Daily patient contacts are sent to the office for patients who agree to be contacted by a Mentoring Angel. Mentoring Angels go through the hospital volunteer process and receive specialized training and coaching. Mentoring Angels volunteers have varied backgrounds and recovery experiences, creating the opportunity for greater connections when volunteers discuss shared experiences and recovery options. Additionally, Mentoring Angels are encouraged to be aware of personal burnout. Burnout is mitigated by limiting volunteer serving to one day a week. Volunteers are debriefed after visits and the volunteer coordinator and interventionists are available to work through difficult visits. By improving upon the processes of recruiting Mentoring Angels volunteers, training and supporting each one, and identifying appropriate patient referrals, we have been able to consistently increase the number of patient referrals and the number of contacts.

Results

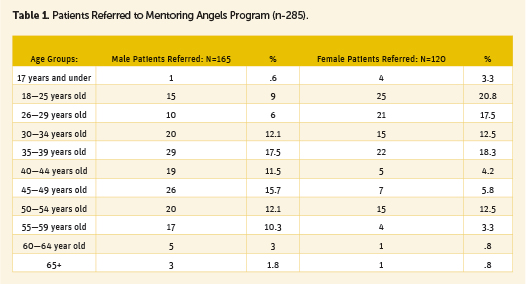

In 2012, 884 patients were contacted for SBIRT interventions. Of those seen by a brief interventionist, 285 patients (31 percent) consented and were referred to Mentoring Angels—165 males and 120 females. Female patients were younger; 34.5 years versus a 41.8 average age for male patients. Most patients were white (93 percent) with African-Americans at 5 percent, Hispanics at 1 percent, and Eastern Europeans at 1 percent.

As noted in Table 1, referrals varied by age and by gender. Ages ranged from under seventeen to age sixty-five, with females being younger.

Case Examples

The following case examples describe two patients who were contacted by a Mentoring Angels volunteer. Patient names and identifying information have been changed.

Rebecca

Rebecca was admitted to the hospital thirty-six weeks into her pregnancy and was experiencing a low grade fever, shortness of breath, dizziness, and overall feelings of malaise. She was diagnosed with a vegetative growth on her tricuspid valve and a septic lesion on her lung. Rebecca reported that she used heroin intravenously and had been drinking heavily for the past four years. She also indicated that she had made a conscious effort to quit drinking when she found out that she was pregnant. However, she reported that she had not been able to quit using heroin but had weaned herself to opiate medications she could buy in the streets. Rebecca also noted that she stopped working at a strip club when she learned she was pregnant and that this helped her reduce her drinking and drug use. Rebecca was detoxified with methadone and started on intravenous antibiotics.

Rebecca was referred to the brief interventionist. Initially, Rebecca was pleasant, but dismissive of any help and support. She noted that she felt awful, was chronically tired, and was dealing with depression as well as grief over the death of her father. However, Rebecca consented to meet with Mentoring Angels volunteers.

During her interactions with a Mentoring Angels volunteer, Rebecca discussed concerns about having her child removed from her custody like her firstborn son, who was living with a family member. Rebecca said she was determined to be the mother that she knew she could be. Rebecca wrestled with the idea of going into a residential treatment facility versus trying to remain clean and sober with supporting outpatient counseling and Twelve Step meetings. Ultimately, Rebecca called to get on a waiting list for a women’s residential treatment program. This was celebrated. She noted how difficult and how important it was for her to ask for help.

During her hospitalization, Rebecca finished her intravenous antibiotics, her lungs and heart valve cleared of infection, and she gave birth to her son. She experienced an emotional letdown when she learned that she would not be able to take her son home because Child Protective Services (CPS) was placing him in foster care until she was able to complete her case plan obligations. Initially, Rebecca did not want to talk about this with the brief interventionist or Mentoring Angels volunteers. However, the next day she was energized and started planning what she needed to do after her hospitalization.

Rebecca continued to visit her son in the neonatal intensive care unit. Although there were no beds available in the residential treatment facility at the time of her discharge, she made arrangements to attend AA meetings and met with her CPS worker. She signed a release, which gave permission to her brief interventionist and Mentoring Angels volunteer to participate in her family care plan meeting. After two weeks, Rebecca entered a women’s residential treatment and called the Mentoring Angels to update her on acceptance into the program. Five months later, Rebecca called and said she had signed out of the residential program a month before. She continued to attend AA meetings two to three times a week, was attending outpatient counseling, and was working on her case plan with CPS to get custody of her son.

Stan

Stan was a thirty-two-year-old male who had a single motor vehicle accident in rural Kentucky. He was flown to the hospital by helicopter for a broken pelvis. Stan’s urine drug screen tested positive for oxycodone, and he was referred for a brief intervention. During the intervention, Stan disclosed that he had snorted oxycodone—120mg to 150mg daily. He added that he cut back and only used an occasional pill when he was doing hard physical labor, but that his drug use had caused significant problems, including financial hardships and legal problems which were contributing to a possible divorce. When asked if drug abuse had a role in his accident, he said that he had taken a pain pill the night before for work-associated pain. He indicated that he swerved to miss a deer, overcorrected, and slammed into a rock wall. Stan said he was concerned about the possibility of going back to using and agreed to meet with a Mentoring Angels volunteer.

Since the Mentoring Angels volunteer was being trained, he was accompanied by an interventionist. The Mentoring Angels volunteer shared his experiences with alcohol and illicit drugs, his quest for recovery, and the positive changes in his life. Stan, with much emotion, said that he relapsed before the accident and had been so high when he was driving that he nodded off and wrecked his new car. Stan also freely discussed the events that led to his abuse of pain pills and his intended steps to enter outpatient treatment after his hospitalization. He spoke with the interventionist about plans for his wife to keep his prescription pain medications at discharge. Stan was discharged from the hospital with a plan to attend NA meetings and an appointment with a mental health counselor.

Summary and Conclusion

This article discusses how SBIRT brief interventions at the University of Kentucky HealthCare are enhanced with follow-ups by recovering Mentoring Angels volunteers. These volunteers share their recovery experiences, strength, and hope with consenting patients. The approach is mutually beneficial for patients, staff, and volunteers, which is underscored by the increased referral rates from brief interventionists at about 30 percent to Mentoring Angels volunteers. Case examples illustrate how peer mentors can help patients address many of the possible barriers they can face including isolation, shame, perceived judgment for their addiction, lack of available community treatment, and hesitations about contacting community recovery support.

The Mentoring Angels program provides an opportunity to go beyond a brief intervention, which typically is one contact. Mentoring Angels volunteers can and do have multiple contacts with patients who are hospitalized for longer periods, or for multiple admissions for medical problems associated with alcohol and/or drug use. Mentoring Angels volunteers also help patients who are contemplating entering treatment or going to a Twelve Step community meeting. The traditions of AA and NA provide outreach to other alcoholics and drug addicts as foundations to their recovery process. Historically, this outreach was in jails and hospitals. Now Mentoring Angels can be a viable option that bridges barriers and supplements brief interventions.

References

Academic ED SBIRT Research Collaborative. (2007). The impact of screening, brief intervention, and referral for treatment on emergency department patients’ alcohol use. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 50(6), 699–710.

Alcoholics Anonymous. (1994). Alcoholics Anonymous, Study Edition. Croton Falls, NY: IWS Inc.

Blondell, R. D., Looney, S. W., Northington, A. P., Lasch, M. E., Rhodes, S. B., & McDaniels, R. L. (2001). Can recovering alcoholics help hospitalized patients with alcohol problems? The Journal of Family Practice, 50(5), 447.

Blondell, R. D., Simons, R. L., Smith, S. J., Frydrych, L. M., & Servoss, T. J. (2007). Initiation of outpatient treatment after inpatient detoxification. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 1(1), 21–5.

Emergency Nurses Association (ENA). (2008). Reducing patient at-risk drinking: A SBIRT implementation toolkit for the emergency department setting. Retrieved from http://www.integration.samhsa.gov/clinical-practice/reducing_patient_at_risk_drinking.pdf

Institute of Medicine (IOM). (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Retrieved from http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2001/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm/Quality%20Chasm%202001%20%20report%20brief.pdf

The Joint Commission. (2014). Topic library item: Substance use. Retrieved from http://www.jointcommission.org/substance_use/

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (1991). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP). (2004). The economic costs of drug abuse in the United States 1992–2002. Retrieved from https://www.ncjrs.gov/ondcppubs/publications/pdf/economic_costs.pdf

OMNI Institute. (2012). SBIRT Colorado: Lessons learned from evaluating the statewide initiative. Retrieved from http://calswec.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/uploads/mhp_03_sbirtcoloradolessonslearned_july2012.pdf

Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1977/2005). The transtheoretical approach: Crossing traditional boundaries of therapy (pp. 147–71). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Rivara, F. P., Koepsell, T. D., Jurkovich, G. J., Gurney, J. G., & Soderberg, R. (1993). The effects of alcohol abuse on readmission for trauma. JAMA, 270(16), 1962–4.

Saitz, R. (Ed.). (2013). Addressing unhealthy alcohol use in primary care. New York, NY: Springer Science.

SAMHSA-HRSA. (2002). SBIRT: Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment; Opportunities for implementation and points for consideration. Retrieved from http://www.integration.samhsa.gov/SBIRT_Issue_Brief.pdf

US Department of Justice National Drug Intelligence Center. (2011). The economic impact of illicit drug use on American society. Retrieved from http://www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs44/44731/44731p.pdf

World Health Organization (WHO). (2014). Global status report on alcohol and health 2014. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/global_alcohol_report/en/

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.