Share

Background and Scope of the Problem

Lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) people display higher rates of hazardous drinking compared to their non-LGB peers (Demant et al., 2017), which are attributable to heightened stressors that disproportionately affect LGB people (McCabe et al., 2009; Meyer, 2003). The Minority Stress Model describes how social stress experienced by LGB individuals, due to identity-related experiences of discrimination, rejection, bias, and microaggressions, combine to create a greater psychological burden on minoritized individuals than on those who are part of the dominant cultural group (Livingston et al., 2017). Minority stressors are perpetuated at systemic and institutional levels, the community level, and at the individual or interpersonal level, including discriminatory laws, social rejection, discrimination, and violence.

These stressors have, in turn, been shown to increase the risk of negative consequences from drinking (Kalb, Roy Gillis, & Goldstein, 2018). These increased risks of negative outcomes for LGB individuals are a major concern, given that alcohol use is associated with leading causes of preventable death in the United States (Mokdad et al., 2018). At the population level, LGB people are disproportionately affected by negative outcomes associated with alcohol use compared to non-LGB individuals, but these studies typically lack information about veteran status. Veterans also tend to have higher rates of alcohol consumption and hazardous drinking than their non-veteran peers (Fuehrlein et al., 2016; Hoggatt et al., 2021). As clinicians, we should consider the impact of intersectionality in our clients’ identities. In this case, how the combination of multiple minoritized identities impacts outcomes in this area. Risks associated with hazardous drinking may be particularly amplified among LGB veterans (Shipherd et al., 2021), given LGB veterans have doubly minoritized identities and discrimination stressors may differentially impact multiply minoritized individuals (Livingston et al., 2019). Thus, it is important to attend to this subpopulation to prevent and address negative alcohol-related outcomes, as well as to reduce health disparities, for LGB veterans.

Why LGB Veterans are a Unique Population Requiring Specific Treatment Recommendations

We live within a broader cultural context where there is a constant threat that LGB peoples’ rights and legal protections will be stripped away, which on its own is a significant stressor (Gonzalez, Ramirez, & Galupo, 2020). Military service adds another layer of complexity, since LGB veterans experienced minority stress in the context of the military cultural legacy of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell (DADT). Under this policy, LGB veterans could not serve openly in the military, or risk being discharged from the military as well as being personally targeted or attacked due to their identity (Livingston et al., 2019).

These and other military cultural factors often lead LGB veterans to conceal their identity to avoid bullying and worse (Burks, 2011). When unit cohesion can make the difference between life and death in a combat situation, responses to perceived threats to cohesion may run the gamut from veiled hostility and ostracizing behaviors to violence in order to produce conformity that is perceived as being required for survival in these extreme contexts. LGB servicemembers experience many types of discrimination and harassment and may be motivated to under-report these events due to fears of retribution and beliefs that their complaints will go unheard due to their sexual orientations (Burks, 2011).

Thus, discriminatory practices are allowed to continue and send the message that individuals with minority identities are not worthy of protection. Military and veteran culture both fail to adequately protect LGB servicemembers and veterans. These differences between military and civilian populations may mean that LGB individuals experience even more harm from discrimination based on their identities, as compared to their non-veteran LGB peers.

Furthermore, the identity of LGB veterans is an intersectional one, with veteran status and LGB identity both possibly being sources of alienation from both the veteran and LGB communities. LGB veterans might not disclose their veteran identity when inhabiting LGB spaces or their LGB identity when in veteran or military spaces due to fears of rejection from both groups, thereby resulting in social isolation, estrangement, and exacerbated minority stress (Livingston et al., 2019). Despite emerging evidence that LGB veterans are at greater risk of experiencing minority stressors and related adverse health outcomes (Harper et al., 2024; Harper et al., 2023), little is known about the degree of hazardous drinking or magnitude of adverse consequences they face as a result of drinking. In our study, we examined differences in alcohol consumption and severity among LGB veterans and non-LGB veterans, as well as risk of alcohol-attributable death between these groups, as a first step toward identifying critical prevention and intervention targets.

The Current Study

Hypotheses/Research Questions

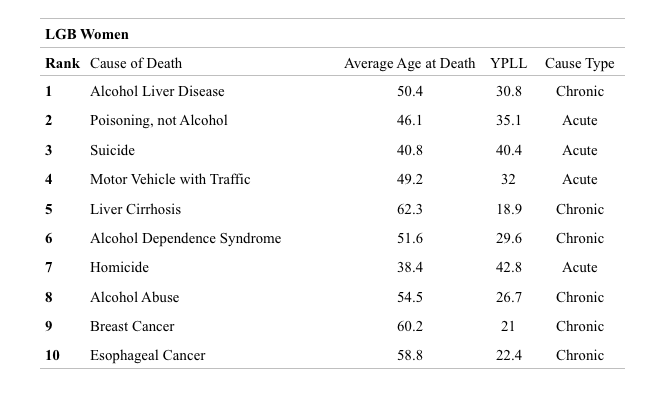

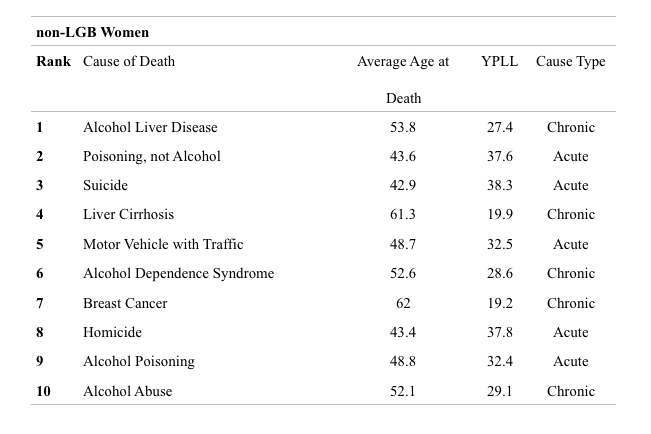

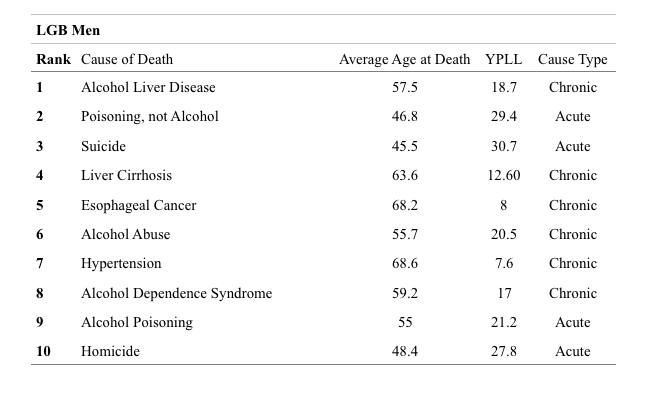

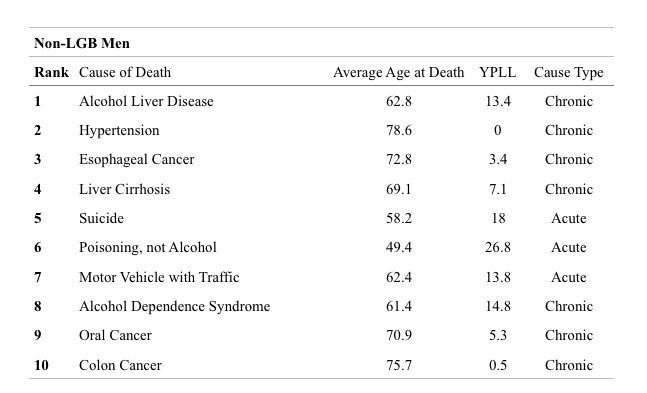

We sought to quantify the years of potential life lost (YPLL), or how many years are lost from an individual’s life expectancy due to an alcohol-attributable death for LGB vs. non-LGB veterans and to specify which causes were most common for different group of veterans (Livingston, Gatsby, Shipherd, & Lynch, 2023; Lynch, et al., 2022).

women, and associated YPLL per cause of AAD by subgroup.

Methods Participants & Data Collection

We used Veterans Health Administration (VHA) electronic health records (EHR) data in this study. We selected individuals whose medical records included alcohol use data (measured via the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test, Consumption subscale; AUDIT-C); and who had not died prior to 2014. The final sample size was a cohort of 102,085 LGB veterans and 5,300,521 non-LGB veterans. The individuals in the LGB veteran group were identified through a combination of natural language processing and machine learning (e.g., to identify LGB individuals based on information written about them in their chart, such as a man being married to another man) and rule-based approached (e.g., ICD codes associated with minoritized sexual identities).

Due to the nature of the data collection, only veterans with LGB identities were able to be categorized, and it was not possible to separate out people who were lesbian, gay, or bisexual. Any veterans who did not have information indicating LGB identity were included in the non-LGB group.

Using death record information, we identified causes of death and also used CDC guidelines for classifying deaths into those that were alcohol attributable. Alcohol attributable causes of death were also further categorized as either acute (e.g., poisoning, suicide) or chronic (e.g., liver disease). We then calculated years of potential life lost (YPLL) per alcohol attributable death by subtracting veterans’ age at death from sex-based life expectancies from 2018.

Results

Overall, there were significant disparities in rates of alcohol-attributable deaths and years of potential life lost based on gender and sexual identity. Compared to non-LGB men veterans, LGB men died five years younger, LGB women died thirteen years younger, and non-LGB women died sixteen years younger from alcohol-attributable causes.

For each group of veterans, the top ten causes of alcohol-attributable death were identified. The most common cause of alcohol-attributable death for all groups was alcohol liver disease, but LGB men and all women died younger from the disease; LGB men died five years younger than non-LGB men (died at 58 vs. 63, respectively) and LGB women died four years younger than non-LGB women (died at 50 vs. 54, respectively). LGB men and all women also had more acute alcohol-attributable causes of death than non-LGB men, with LGB men and women dying younger of acute causes than non-LGB women. LGB men and all women were significantly more likely to die by alcohol-attributable suicide and at younger ages compared to non-LGB men. LGB men and all women also had homicide in their top ten causes of alcohol-attributable death, while non-LGB men did not.

Discussion

These studies highlight clear disparities in the impact of drinking on LGB vs. non-LGB veterans, indicating that the current status quo for treatment of these issues is not sufficient for the prevention of alcohol-attributable death. It is important to understand why these differences in alcohol-attributable deaths exist; potential drivers of these disparities could relate to military context, gender differences, or the myriad of adverse circumstances that affect LGB people relative to their non-LGB peers. One hypothesis for why these differences might occur is that LGB veterans are less likely to utilize health care services than their non-LGB counterparts, due to fears of stigma from health care providers or as a result of past negative experiences within the military or the VA (Harper et al., 2023; 2024; Livingston et al., 2019).

However, this hypothesis is not borne out by the data—LGB veterans were equally or more likely to use medical services than their non-LGB counterparts, so the health care needs of these individuals, in regards to their substance use, are being missed for other reasons (Lynch et al., 2022). Thus, we offer recommendations for providers to help avoid these negative outcomes among LGB veterans.

Recommendations

Assess Both Sexual Orientation and Substance Use: It is necessary for clinicians to signal safety for veterans to disclose sensitive information like sexual orientation and substance use in treatment settings. Providers may avoid asking about these topics out of fear or discomfort, but the impact of this is that clients may not be adequately screened nor receive the necessary help. Veterans may be even more likely than non-veterans to conceal information about sexual orientation due to experiences while in the military. Providers can signal safety for discussing these topics by asking about sexual orientation in a direct, matter of fact, and non-pejorative way.

Even if these efforts do not bear fruit early on in the counseling relationship before rapport is built, it establishes that the provider is not working from a paradigm that sees straightness as the default and all other sexual orientations as deviations from the norm. Thus, when the client feels comfortable disclosing, the precedent set by the earlier conversation can reduce the barriers to disclosure. These principles all hold true for discussion of substance use as well.

Assuage Fears about Confidentiality: LGB veterans may experience significant fear about disclosing minority identity to a health care provider due to the history of punishment for these identities in the military. There is also the discriminatory legacy within the mental health field which pathologized LGB orientation until 1973 (Drescher, 2010) and in light of previous practices that have since been deemed ineffective and unethical (e.g., sexual orientation change efforts, “conversion therapy”; Haldeman, 2002).

Briefly discussing guidelines surrounding confidentiality and clarifying who has access to the information written in session notes can allow LGB veterans to make informed decisions about if or when to disclose. During this conversation, providers can describe what information is included in clinical notes (while staying within the limits of confidentiality) and possibly initiate a dialogue about whether or not to include sexual orientation information in notes. Letting that process be interactive, rather than something imposed on veterans against their will, may increase the chances that a veteran feels safe to disclose.

Screen for Alcohol Use and Consequences More Regularly, Especially Among Women: This article’s results indicate that LGB veterans are not receiving treatment early enough to arrest the progression of alcohol-related harms. Thus, it is first necessary to assess for substance use more regularly and its potential health risks so that providers and clients have a shared understanding of the client’s substance use behaviors.

Under-reporting of substance use is incredibly common and may be more likely for heavier drinkers (Boniface, Kneale, & Shelton, 2014), so it is necessary to discuss substance use in an ongoing way through the course of treatment, and in a manner that is non-judgmental and non-punitive. As the provider and client build trust, the client may be less likely to minimize their substance use, allowing the provider to make more accurate recommendations on how to reduce harms from substance use. Further, the counselor can discuss with the client other health appointments and aspects of physical wellbeing as part of the counseling relationship.

Use of techniques such as motivational interviewing (MI; Miller & Rose, 2009) may increase the effectiveness of these discussions for changing the client’s current health behaviors. Regardless of the counseling or therapeutic orientation of the provider, it is necessary to explore client health and impacts of substance use in a person-centered, nonjudgmental way to achieve better outcomes and research shows that provider stigma leads to poorer outcomes (Van Boekel, Brouwers, Van Weeghel, & Garretsen, 2013). Having positive conversations about substance use and its health impacts with one provider may increase the likelihood that clients will accept referrals to other medical providers as needed.

There is also the finding that LGB veterans and women veterans were more likely to die and die younger of acute causes like suicide or homicide. Homicide was in the top ten causes of death for all groups aside from non-LGB male veterans. The acute nature of this subset of alcohol-attributable deaths in contrast to deaths causes by chronic conditions means that these types of deaths require different prevention strategies.

To that end, it is important for providers to assess more than just quantity and frequency of alcohol use. Aspects of veterans’ drinking contexts (e.g., drinking heavily in unfamiliar places, around unfamiliar people, or in unsafe locations) and risky behaviors while drinking (e.g., when impulsivity is heightened) may contribute additional risk for women and LGB men, warranting careful assessment and harm-reduction interventions. Performing a nuanced assessment of alcohol use and its situational context may identify other risk factors for acute causes of death that can be addressed in treatment.

Understand How Minority Stressors Can Impact the Counseling Relationship: The impact of minority stressors on the therapeutic alliance may be especially relevant for veterans who have lived through DADT and its aftermath (Johnson, Rosenstein, Buhrke, & Haldeman, 2015). Veterans with minoritized sexual identities may have experienced bias and homophobia from individuals with power, possibly even from medical providers (Mattocks et al., 2015; Simpson et al., 2013). The impact of these fears around discrimination can have many negative outcomes, both on emotional functioning and perceived psychological safety in the counseling room.

LGB veterans who present to counseling may experience shame, expectations of rejection, and a belief that it is necessary to conceal their sexual identity (Van Gilder, 2017). Negative experiences with others as a result of sexual orientation eventually get “under the skin” through reinforcement and punishment from the environment, and individuals acquire behaviors to protect themselves from discrimination (Hatzenbuehler, 2009).

Substance use may function as a means to cope with experiences of rejection and identity-based stigma and the negative emotions that result from these experiences. Given that many of the learned protective behaviors against discrimination (particularly in military contexts) involve concealment, more adaptive ways of coping may not be available to these individuals and alcohol use may appear significantly more attractive as a result. In this way, alcohol use may be connected to experiences of discrimination and stigma, and thus it is even more vitally important that providers discuss substance use and functional associations with minority stress that may be driving substance use, with these clients in a non-stigmatizing way. Providers can also now learn interventions that address the specific harms of minority stress (e.g. ESTEEM, Pachankis et al., 2015; EQuIP, Pachankis et al., 2020) to improve competence in this area and efficacy in their work with clients.

Positive relationships with providers who can be affirming of multiple aspects of LGB veteran identity can be a healing experience for these clients. LGB veterans may fear to disclose their veteran identity in LGB spaces, and vice versa, and thus be cut off from emotional support and community as a result. Veterans may feel alienated from both communities as a result of their membership in the other, and crave understanding of both aspects of their identity, which can happen in a positive therapeutic relationship. A single affirming relationship with a provider can facilitate a client building a larger health support network for better health outcomes across the board.

Limitations: This study relied on clinical notes in the EHR to identify LGB people, which required identity disclosure to providers in some way. This was because sexual orientation data was not routinely captured in the medical record at the time. Thus, it is not possible to generalize the findings to LGB veterans who did not self-identify or those for whom LGB identity was not documented in their notes. It is possible that veterans who were more likely to disclose sexual orientation or have it documented might also be more likely to disclose substance use severity. However, it is equally if not more likely that the actual story here is even worse than the data would indicate; if LGB people were included in the group of non-LGB people in our comparison group, it is possible that the magnitude of the disparities may be even more stark.

Conclusions

LGB people and veterans are at greater risk for hazardous drinking. In this study, we found that LGB veterans, as compared to their non-LGB counterparts, were significantly more likely to die of alcohol attributable causes. When they did die of alcohol attributable causes, LGB men tended to die years younger than their non-LGB counterparts, and women (regardless of sexual orientation) were at particularly high risk. LGB men and all women were also more likely to die of acute causes, indicating that assessing contextual information around alcohol use may be even more important for those sub-groups, such as how they drink, when and where, and with or around whom.

For instance, the fact that alcohol attributable homicide and suicides ranked higher for LGB men and women (regardless of sexual orientation) suggest that it is essential to consider harm-reduction strategies in counseling. To offset risk of premature death, providers have a duty to address the causes of these disparities through better assessment and prevention efforts, and creating an environment of trust and acceptance so that accurate information is captured through better and more frequent assessment. Relatedly, we strongly encourage not only careful screening of sexual orientation and alcohol use, but also alcohol related consequences and contexts in which drinking occurs.

It is important for providers to not solely or even primarily focus on deficits when these identities can also be a source of strength. Providers can and should assess how veteran and LGB identities can be a source of joy, pride, meaning, and resilience for each individual client, and assist clients in finding community that values and accepts all aspects of their identities. Although there may be additional challenge in finding community and acceptance for individuals who have multiply minoritized identities, we as providers should also celebrate our clients’ uniqueness and support them in finding their desired manner of expression and connection. We must not treat our clients as fragile, but rather as strong and competent partners in the work of healing and flourishing.

References

- Boniface, S., Kneale, J., & Shelton, N. (2014). Drinking pattern is more strongly associated with under-reporting of alcohol consumption than socio-demographic factors: evidence from a mixed-methods study. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 1-9.

- Demant, D., Hides et al., (2017). Differences in substance use between sexual orientations in a multi-country sample: findings from the Global Drug Survey 2015. Journal of Public Health (Oxford, England), 39(3), 532–541.

- Drescher, J. (2010). Queer diagnoses: Parallels and contrasts in the history of homosexuality, gender variance, and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 427-460.

- Fuehrlein, B. S. et al., (2016). The burden of alcohol use disorders in US military veterans: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Addiction, 111(10), 1786-1794.

- Goldbach, J. T., & Castro, C. A. (2016). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) service members: Life after don’t ask, don’t tell. Current Psychiatry Reports, 18(6), 56.

- Gonzalez, K. A. et al., (2020). Increase in GLBTQ minority stress following the 2016 US presidential election. The 2016 US Presidential Election and the LGBTQ Community (pp. 130-151).

- Haldeman, D. C. (2002). Gay rights, patient rights: The implications of sexual orientation conversion therapy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 33(3), 260.

- Harper, K. L. et al., (2024). Examining differences in mental health and mental health service use among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual veterans. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity.

- Harper, K. L. et al., (2023). Experiences of discrimination and mental health treatment seeking among LGBQ+ veterans. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity.

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2009). How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin, 135(5), 707.

- Hoggatt, K. J. et al., (2021). Prevalence of substance use and substance-related disorders among US Veterans Health Administration patients. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 225, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0376871621002866

- Johnson, W. B. et al., (2015). After “Don’t ask don’t tell”: Competent care of lesbian, gay and bisexual military personnel during the DoD policy transition. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 46(2), 107.

- Kalb, N., Roy Gillis, J., & Goldstein, A. L. (2018). Drinking to cope with sexual minority stressors: Understanding alcohol use and consequences among LGBQ emerging adults. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 22(4), 310-326.

- Livingston, N. A. et al., (2019). Experiences of trauma, discrimination, microaggressions, and minority stress among trauma-exposed LGBT veterans: Unexpected findings and unresolved service gaps. Psychological Trauma : Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 11(7), 695–703. https:// doi.org/10.1037/tra0000464

- Livingston, N. A. et al., (2023). Causes of alcohol-attributable death and associated years of potential life lost among LGB and non-LGB veteran men and women in Veterans Health Administration. Addictive Behaviors, 139, 107587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107587

- Lynch, K. E. et. al., (2022). Alcohol-attributable deaths and years of potential life lost due to alcohol among veterans: Overall and between persons with minoritized and non-minoritized sexual orientations. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 237, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.10953

- Mattocks, K. M. et al., (2015). Perceived stigma, discrimination, and disclosure of sexual orientation among a sample of lesbian veterans receiving care in the Department of Veterans Affairs. LGBT Health, 2(2), 147-153.

- McCabe, S. E. et al., (2009). Sexual orientation, substance use behaviors and substance dependence in the United States. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 104(8), 1333–1345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360- 0443.2009.02596.

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Miller, W. R., & Rose, G. S. (2009). Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. American Psychologist, 64(6), 527.

- Mokdad, A. H. et al., (2018). The state of US health, 1990–2016: Burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors among US states. Journal of the American Medical Association, 319(14), 1444–1472. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.0158

- Pachankis, J. E. et al., (2015). LGB-affirmative cognitive-behavioral therapy for young adult gay and bisexual men: A randomized controlled trial of a transdiagnostic minority stress approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(5), 875.

- Pachankis, J. E. et al., (2020). A transdiagnostic minority stress intervention for gender diverse sexual minority women’s depression, anxiety, and unhealthy alcohol use: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(7), 613.

About Me

Lauren McClain is a clinical psychology intern at VA Boston, completing her graduate studies in clinical psychology at the University of Washington. Lauren’s research involves ecological momentary assessment of drinking to cope with emotional distress, and how drinking to cope predicts negative consequences from alcohol use. As a clinician, Lauren is interested in substance use treatment for clients with PTSD, and how building mindfulness and emotion regulation skills can increase resilience for these clients.

Dr. Anne Banducci is a staff psychologist and military sexual trauma care coordinator at the VA Boston Health Care System, as well as an assistant professor of Psychiatry at the Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine. Dr. Banducci’s clinical work and research focus on better understanding and treating co-occurring PTSD and substance use disorder. Within her clinical practice, she enjoys utilizing treatments like prolonged exposure therapy, motivational interviewing, CBT, DBT, as well as supervising psychology trainees in these treatment modalities. Within her research, she hopes to do work that meaningfully improves the lives of underserved individuals whose needs are currently not being met.

Dr. Nick Livingston is a research psychologist in the National Center for PTSD, Behavioral Science Division, and assistant professor of Psychiatry, Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine. Dr. Livingston conducts research on opioid and alcohol use disorder treatment best-practices and outcomes, the longitudinal course of co-occurring substance use disorder and PTSD, and trauma and minority stress-related drivers of psychiatric disparity among LGBTQ+ people. He is also a practitioner at VA Boston Health Care System.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.

Counselor Magazine is the official publication of the California Association of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP). Counselor offers online continuing education, article archives, subscription deals, and article submission guidelines. It has been serving the addiction field for more than thirty years.